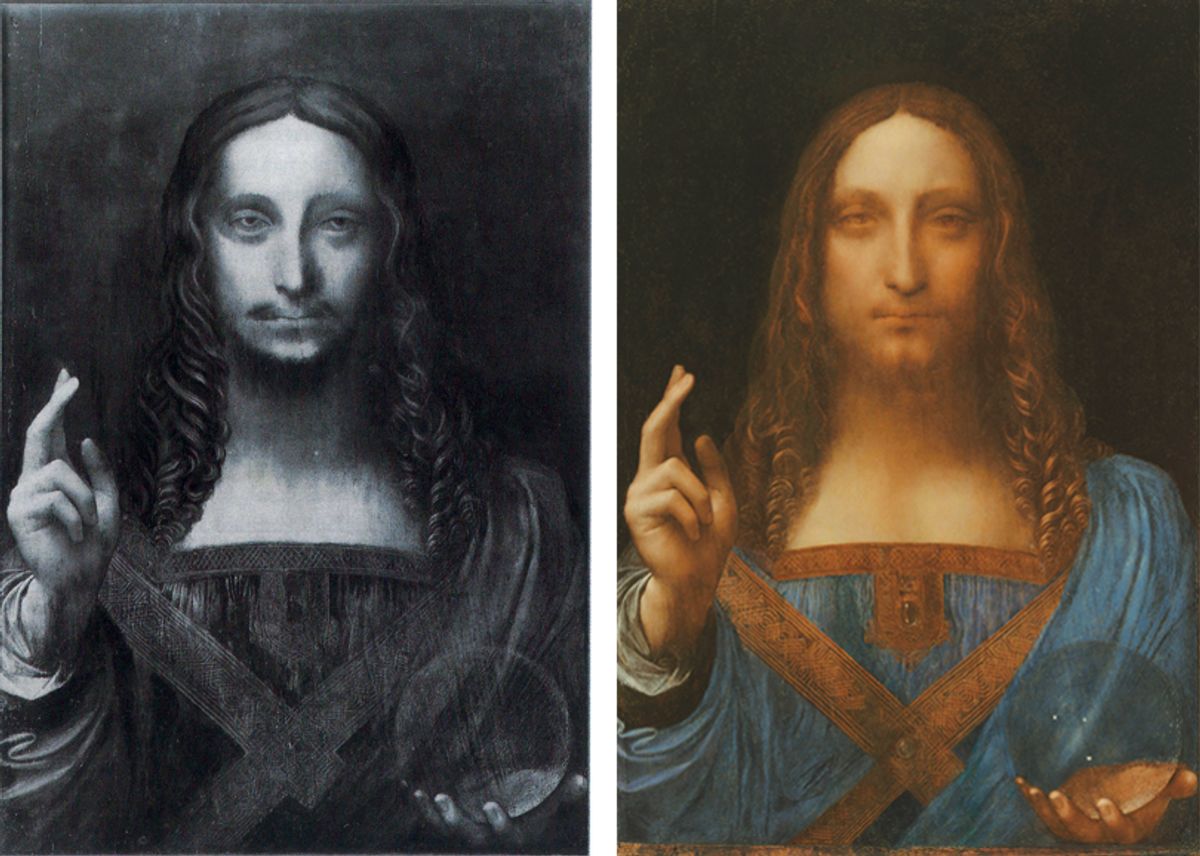

A painting once sold by Sotheby’s for £45 will fetch around $100m when it comes up for auction at Christie’s New York on 15 November. The Sotheby’s sale was back in 1958, when the work, known as the Salvator Mundi (saviour of the world), covered by overpainting, and went unrecognised as a work by Leonardo da Vinci. Now the painting is accepted by almost all specialists as being by the artist and has been dated to around 1500.

The seller of the work is the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. He is in dispute with his Swiss former art adviser, Yves Bouvier, who is said to have bought the Salvator Mundi for around $80m and sold it on to Rybolovlev for $127.5m in 2013. Legal proceedings are continuing between the two men over a series of sales.

Christie’s has given an estimate of “in the region of $100m”. The painting has a “guaranteed” third-party buyer and will therefore sell at a price close to the estimate or more. (If there are no other bids above the reserve, then the work will go to the guarantor, but if the price goes higher, then the extra money will be shared between the auction house and the guarantor.) The painting will far exceed the record price for an Old Master at auction, currently held by Rubens’s Massacre of the Innocents (1611-12), which sold for £49.5m in 2002.

Christie’s says that the Salvator Mundi is among fewer than 20 surviving paintings that are almost universally accepted as being by Leonardo. (Some specialists would narrow it down to around 15.) The only serious doubts have been raised by Carmen Bambach, an Italian Renaissance specialist at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. She tells The Art Newspaper that “much of the painting may have been done by Giovanni Boltraffio [a studio assistant], with passages by Leonardo”.

But Bambach is very much in a minority and those supporting the Leonardo attribution include Nicholas Penny, the former director of the National Gallery in London (where the painting was unveiled in 2011, in the institution’s Leonardo exhibition). He tells The Art Newspaper that he is “convinced” it is by the master.

The rationale for the attribution includes style and technique; the existence of two preparatory drapery drawings in the Royal Collection; a 1650 etching by Wenceslaus Hollar; the quality of the blessing hand and hair; the painting’s superiority compared with the 20 or so surviving copies; technical analysis of the pigments and media; and the existence of pentimenti such as the thumb of the blessing hand.

The work is being sold in the auction house’s evening post-war and contemporary auction on 15 November. This surprising decision represents an attempt to woo new collectors who might not normally consider Old Masters. In practice, however, it will effectively be a one-work auction with its own catalogue. Last month, the painting went on tour to Hong Kong, San Francisco and London before travelling to New York. The choice of Hong Kong suggests that Christie’s believes there will be strong East Asian interest.

Commenting on its condition, a Christie’s spokeswoman says that, as a 500-year-old painting, “it has endured some wear and tear over the centuries”. She adds that “many of the most important elements—the blessing hand, the orb, Christ’s vestments, the curls in his hair—are remarkably intact”. However, the panel has suffered a serious vertical crack on the left side and the face was overcleaned, possibly in the early 17th century.

Riches to rags to riches

Provenance research suggests that the Salvator Mundi may have been commissioned by France’s King Louis XII and that it was later owned by Charles I of England. It was acquired by the Duke of Buckingham in 1688 and was sold by his descendants as a Leonardo in 1763.

The work then went missing until it was bought in 1900 for the collection of Francis Cook, when it was attributed to a follower of Leonardo. Upon the dispersal of Cook’s collection in 1958, it was sold at Sotheby’s London as a copy after Boltraffio for £45 to a buyer named Kuntz. It was bought by an American and, after a family death in 2005, was sold at a small, regional auction in the US (possibly in Louisiana or Virginia), apparently without an attribution. The price is believed to have been less than $10,000.

Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

The painting was acquired by a trio of New York-based dealers: Robert Simon, Alex Parish and Warren Adelson. The dealers’ consortium, known as the R.W. Chandler company, had the work thoroughly investigated by specialists and then conserved by Dianne Dwyer Modestini in New York.

In 2012, the Dallas Museum of Art came close to buying the Salvator Mundi for an undisclosed price, believed to be up to $100m.