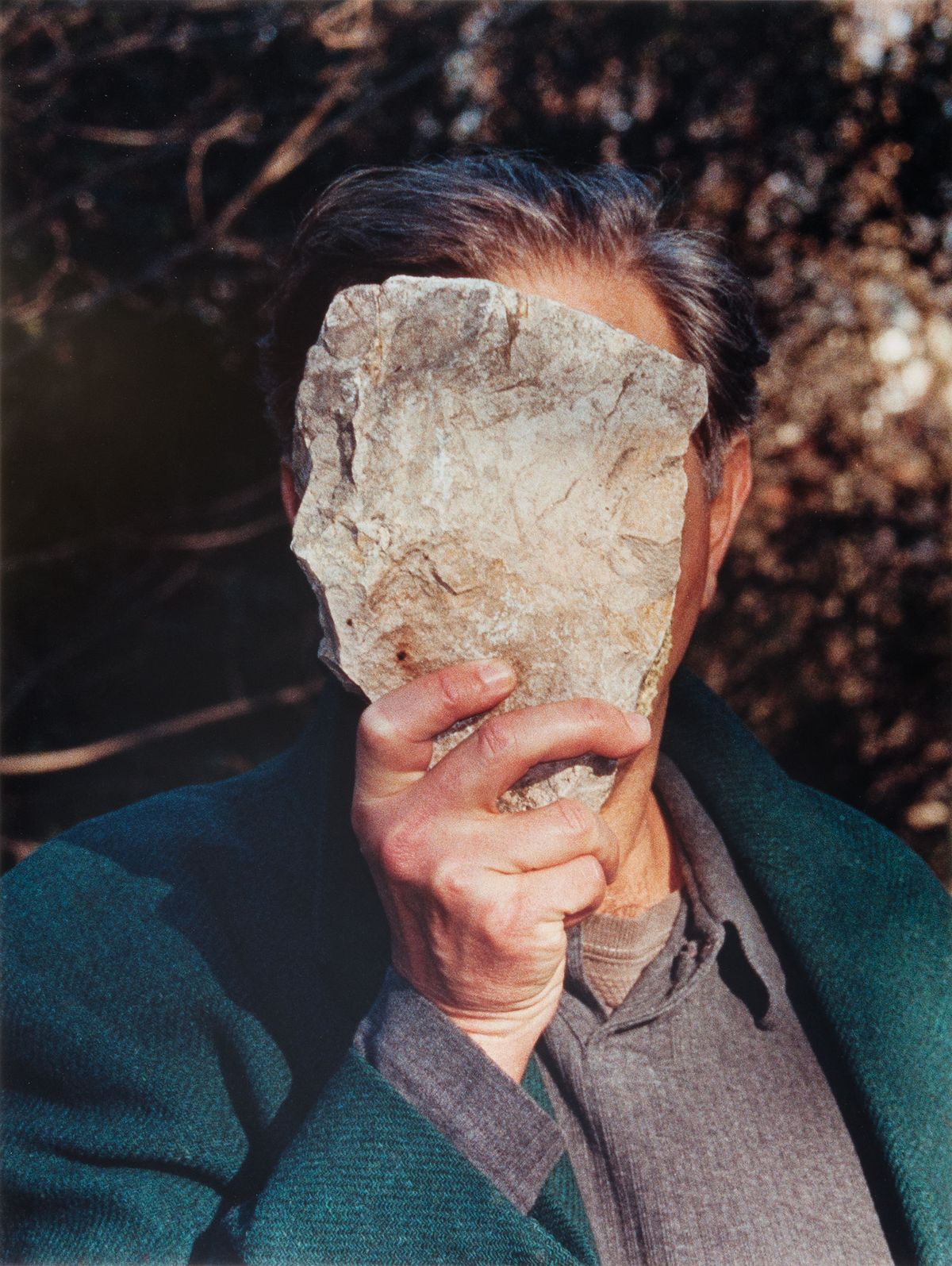

Towards the end of the American artist Jimmie Durham’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York, there are three self-portraits that succinctly capture the 77-year-old artist’s practice. In one, he wears a mask to look like the artist Maria Thereza Alves, his partner of almost 40 years. In another, he is dressed as Rosa Levy, a character referring to Marcel Duchamp’s alter ago, Rrose Sélavy. In the last work, Self-Portrait Pretending to Be a Stone Statue of Myself (2006), Durham holds a rock the size of his head in front of his face, so that he is completely obscured.

Which of these self-portraits is the most true? Is it the one as Rosa Levy character, seemingly a perfect distillation Durham’s self-image? Or is it the one where he plays Alves, whom he knows as well as anyone and whose sensibilities may have partly become his own? His face is invisible in the picture with the stone, but perhaps it is the neatest summary of Durham’s sense of himself. There are stones are everywhere in this exhibition, although no two are exactly alike, making them ideal stand-ins for the artist’s many presences.

Or maybe the answer is that they are all a little true, and all a little false

“I am accused, constantly, of making art about my own identity,” Durham said in 2011. “I never have.” But the idea that identity is not static and is at least partly self-invented is strengthened at every turn in the exhibition, his first solo show in the US in 22 years. Among the 120 works on view, there is wooden sculpture of a walking, Giacometti-like figure who holds (according to the artist) Durham’s actual teeth; a Bruce Nauman-esque work of seven cast bronze human noses; and a striking and tender portrait made of mud and glass with a button nose, smiling and shy.

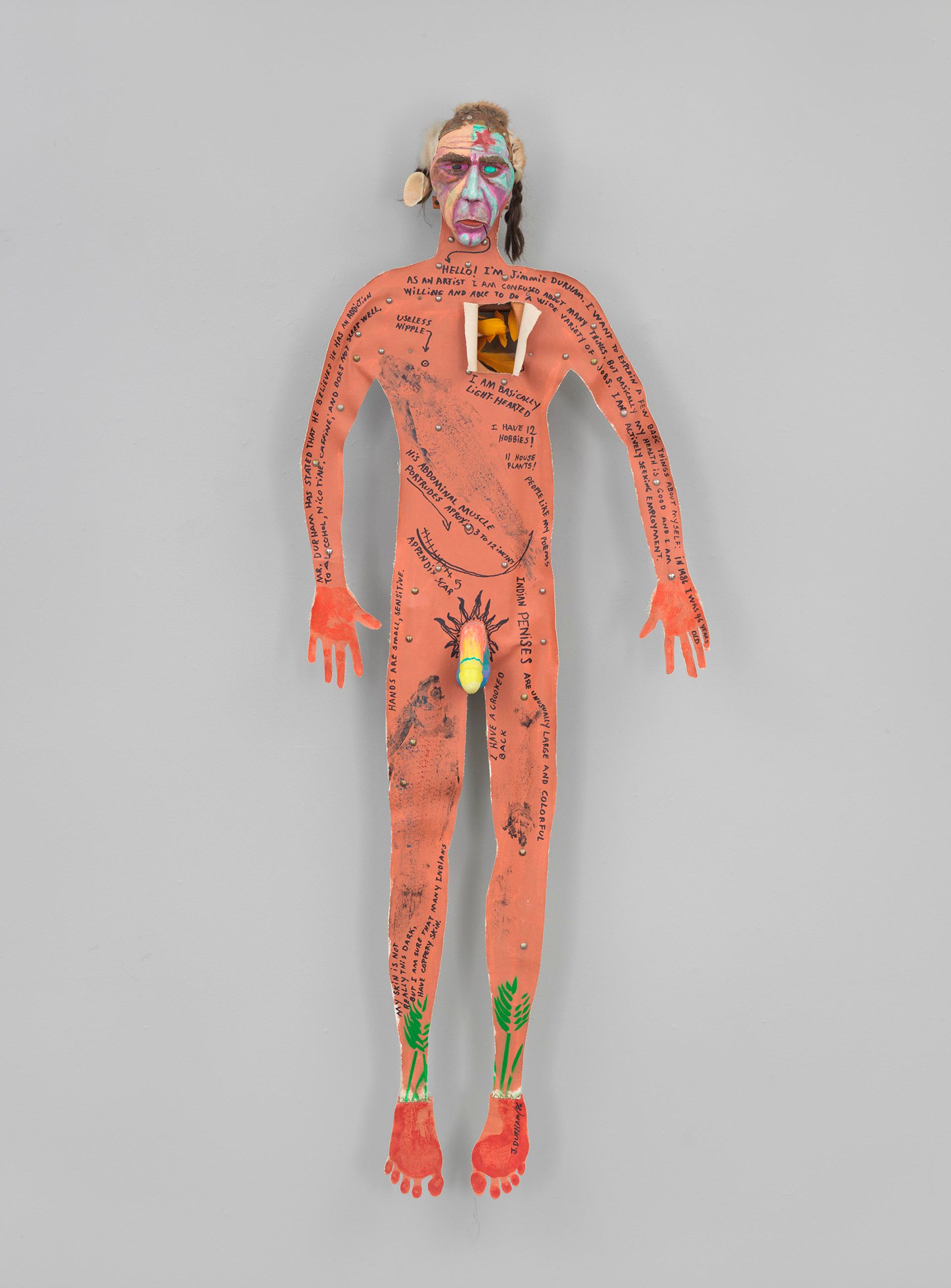

There are also many references to Durham’s personal history, and specifically his claims of Cherokee ancestry. His sculpture titled Self-portrait (1986) depicts him with red skin, a painted face and a note scrawled beside his mostly yellow penis: “Indian penises are unusually large and colourful.” Across the chest and left arm, Durham wrote his name, age and that he is “actively seeking employment”.

Digital image Whitney Museum, NY

Durham is a cutting satirist. He can make a serious argument in one turn and gently undermine it in the next, to orchestrate a layered and rich conversation. He is nimble with tools and materials, has a strong sense of craft and is an excellent colourist. His muted but varied palette echoes his insight into the variety that makes up any single perspective. He is sensitive, ultimately, to the many parts that make up a person and insists on the complexity, not singularity, of his Cherokee identity.

But his Native American lineage has been regularly called into question, with a committee of Cherokee writers, artists, curators and a councilwoman writing a letter in June, when the retrospective was on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, stating that Durham is not registered with either of the three bodies that can confer Cherokee citizenship. More importantly, they say, “Durham has no Cherokee relatives; he does not live in or spend time in Cherokee communities; he does not participate in dances and does not belong to a ceremonial ground.”

For much of the past two decades, Durham, who now lives in Europe, has skirted the issue, downplaying his claims as he has pursued other ideas. Some of his best sculptures from this period, like Arc de Triomphe for Personal Use (1996)—a meagre, flimsy and misshapen version of the grand Parisian monument—have nothing to do with “Indian-ness”. Nor does The Dangers of Petrification II (1998-2007), which has a glass vitrine full of stones that look like various meats and cheeses.

His clearest, though still quiet, rejoinder to his critics comes in his 2004 video Smashing, in which he sits at a desk in a suit like a bureaucrat and receives visitors. Each person brings an item—a guitar, a melon, a bag of flour—that Durham smashes with a rock. He then stamps a document, signs his name, and hands it over. This is a wry and compelling take on the inadequacy of any official registry. Yet the Cherokees who deny Durham’s ancestry are not concerned about bureaucracy. “This is not a small matter of paperwork”, the committee said, “but a fundamental matter of tribal self-determination and self-governance.”

There are many truths in this show, and one is that Durham is a great American artist that deeply understands the mutability of who we are. Another is that identity is never completely self-selected and that we do not have absolute control in creating our personal histories—a lesson Durham still needs to learn.

• Jimmie Durham: at the Centre of the World, Whitney Museum of American Art, until 28 January 2018