Many assume that once a collection, especially one comprised mostly of Old Master paintings, has graced a museum’s walls for a century, everything that can be learned already has. But an exhibition opening on 3 November at the Philadelphia Museum of Art turns that theory on its head. New technical and art-historical research on eight of the 100 works on display proves that there are still secrets waiting to be revealed.

The show includes a selection of the 1,279 paintings, 51 sculptures and 100 objects bequeathed to the museum in 1917 by the Philadelphia lawyer and collector John Graver Johnson. “It’s one of the largest and most significant collections of European paintings in the US,” says Christopher Atkins, the museum’s associate curator of European paintings. The exhibition’s two-year lead time afforded curators and conservators the opportunity to study pieces from the Johnson collection and show the public that it “is not a static collection but a living one, with loads of potential for new discoveries”, says the museum’s director of conservation, Mark Tucker.

Skeletons in the cupboard

Judith Leyster, The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier) (around 1639)

Although the museum had known since the 1970s that there was more to The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier) (around 1639), by the Dutch artist Judith Leyster, its conservators only recently were able to remove overpaint, revealing a skeleton that Leyster had included as a moralising tale of what happens to those who drink to excess. “We didn’t know enough about the painting’s condition to determine if the overpaint could be removed without causing any damage,” says the museum’s director of conservation Mark Tucker. He suspects that the skeleton was removed before Johnson bought it in 1908 to make it more marketable.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

I’ll see your cardinal and raise you an archbishop

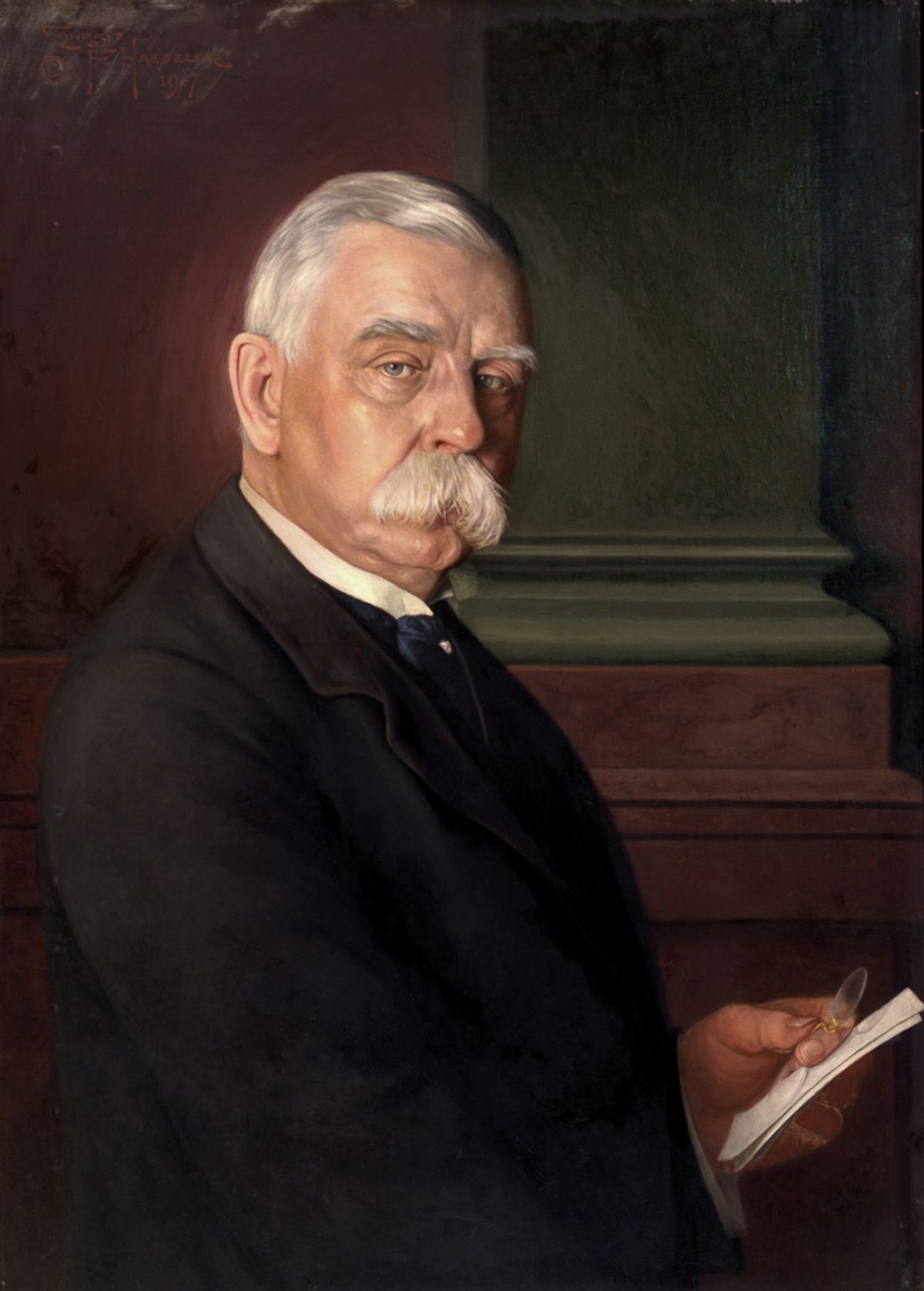

Titian, Filippo Archinto (1558)

Museum staff studied Titian’s 1558 portrait of Filippo Archinto (pictured right, before conservation), a work that had not been treated in 50 years. According to the senior conservator of paintings Teresa Lignelli, who worked with the conservation scientist Kate Duffy on the picture, their aim was to improve its appearance and gain a better understanding of it “so we could answer the question that I’m so often asked, namely: ‘What’s wrong with it?’” For years, scholars assumed that the work was painted when Archinto was a cardinal because of the reddish colour of his robes. Lignelli and Duffy determined that Titian painted Archinto after he was made an archbishop in 1556 and that his cloak or mozzetta was originally purple. To create the mozzeta, Titian mixed red organic colourant with smalt, a pigment that was popular in Venice at the time but is unstable and loses its blue colour over time. “The left side of the mozzetta had degraded to a brownish-red colour, while the right side retains a purplish hue, suggesting that the lead white pigment used to paint the white veil may have offered a protective environment for the smalt,” Duffy says.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

The bigger picture

Attributed to Rogier van der Weyden, The Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning (around 1460)

The museum now believes that this composition attributed to Rogier van der Weyden, which was split into two panels at some point, formed part of a lost, large-scale altarpiece by the Netherlandish master. The panels had intrigued conservator Mark Tucker for years because scholars could not agree on what they were. He revisited technical reports and honed in on “an odd carpentry detail that seemed insignificant at first”, he says. He determined that a piece of woodwork had been secured to the opposite side of the composition with dowel holes in a manner consistent with the construction of Netherlandish carved altarpieces. “We now know of paintings produced in Van der Weyden’s workshop that link directly to a sculptural project,” he says. “Our research indicates that it came from a lost altarpiece, with a level of sophistication suggesting it was one of the monumental achievements of 15th-century Northern European art.”

• Old Masters Now: Celebrating the Johnson Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 3 November-19 February 2018