When the British Council, in co-operation with the Department for Digital, Media, Culture and Sport, was tasked with developing a fund for the protection of heritage in 12 conflict-affected countries in the Middle East and Africa, the desire was to “create something open and transparent that would not run the risk of becoming a pet project”, says Stephen Stenning, the council’s director of culture and development. The idea was to encourage economic development by building capacity to foster, safeguard and promote heritage in these regions. It was created in anticipation of the UK’s ratification of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, which the government finally ratified in September. Over the past two years, the £30m Cultural Protection Fund has awarded “roughly £11m” to 22 projects ranging from safeguarding Turkey’s archaeological sites to recording the oral histories of nomadic Bedouin communities of the Occupied-Palestinian Territories.

So far, the four-year fund has received 138 “full” or complete applications seeking a total of £294m. After initial requests for grants of £2m to £3m it is beginning to receive more applications for smaller amounts. When it launched in 2016, applicants could apply for up to £3m, but that figure was reduced to £2m after the first round because of the large number of requests for the maximum amount. There was concern that “it would be difficult to cope” with too many £3m projects, Stenning says, adding that although the literature discourages it, there is nothing to prevent someone from applying for more than £2m.

Stenning is amazed at the positive response the initiative has received. He says that allowing smaller institutions and local organisations to work directly with universities and museums on development projects has helped to make the fund a success. Having local project partners involved at every level is a key element of the model. If the lead partner organisation is based outside the country it must deliver the project with at least one partner organisation in the region.

He also credits the UK’s attitude towards heritage. “Our definition is not just what experts say it is but what people value or see as their identity and what they want to pass on to future generations,” Stenning says. Intangible heritage projects have received funding from the start. “In times of conflict, intangible heritage comes up a lot. Of course, Damascus’s historic buildings are important, but so are the recipes, songs and things that remind you of your history because they are the keys to your future,” he says, adding: “It makes you believe that there is something that will live on after this.”

The Cultural Protection Fund is secure until March 2020. A British Council spokeswoman tells us that the government’s recent cut to the council’s developed countries grant in aid has “no bearing” on the fund as it is UK Government official development assistance money, which “is separate from our core funding”. While Stenning admits there are “no direct plans to extend the fund’s current incarnation anywhere else at the moment”, he does reveal that there has been “interest” in how this model could be used in other parts of the globe, and not just to protect heritage imperilled by war but also by natural disasters. He says it could also offer an alternative to the destination tourism model when discussing heritage as a driver of economic growth.

How the fund is helping to preserve heritage

World Monuments Fund

Syrian stonemasons: £536,671

Historically, stonemasons from Syria have been some of the finest practitioners of the craft. But even before the outbreak of the civil war, the number of skilled stonemasons was in decline. The World Monuments Fund Britain is working with the Petra National Trust to train a new generation of Jordanian students and Syrian refugees in traditional stonemason skills, including ornamental and practical cutting techniques, practical conservation processes and stabilisation methods, to equip them with the tools they need to repair heritage buildings damaged during the war. “The project contributes towards regeneration efforts in both a direct and indirect way, in that it will physically help to rebuild historic buildings and give displaced people practical skills and a sense of identity, respectively,” says Stephen Stenning from the British Council. Recruitment for the 42-week course began in September.

Yazidi heritage and identity: £96,800

The number of Yazidis displaced during the ongoing conflicts in Syria and Iraq is estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands. This innovative project involves training around 15 displaced Yazidi youths in all aspects of documentary film-making to prepare them to produce ten films on oral histories associated with 30 shrines in Iraq, specifically those in Dohuk, Mosul and Sinjar. These shrines are central to Yazidi identity, so many of the historic structures were destroyed by Islamic State as part of the terrorist group’s campaign to eradicate Yazidi culture. The films, which will be screened at international film festivals, will also touch upon different approaches to the restoration of the shrines, their role in tourism and future management plans. “The project looks to protect traditions and ways of life,” Stenning says. “With such large-scale displacement as this, it is important to gather the stories as well as care for the buildings and collections left behind.”

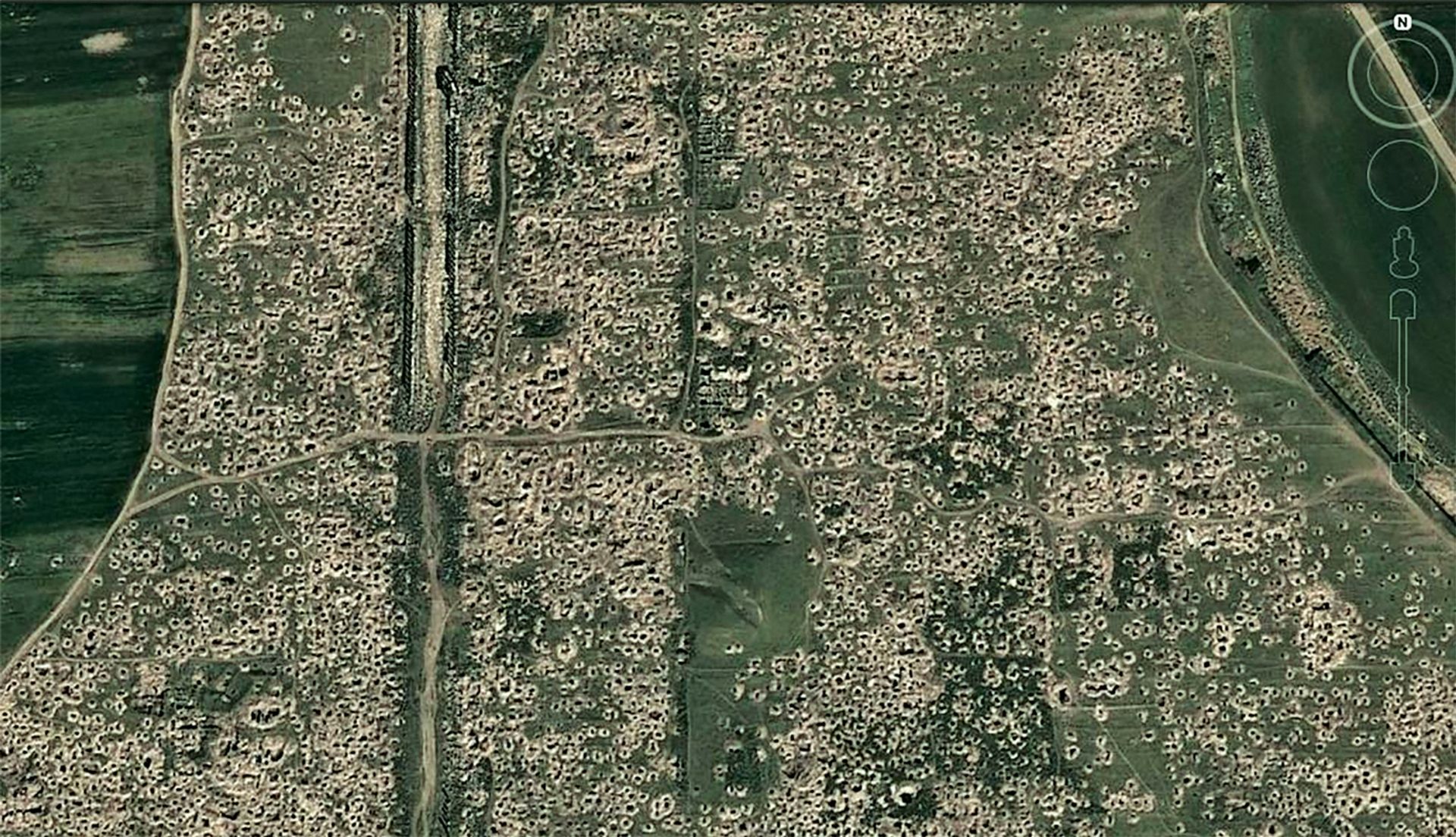

Aerial recording of endangered archaeological sites: £1,714,124

It was not until satellite images of ancient sites such as Apamea in Syria showing “lunar landscapes”—a term used to describe the hundreds of tiny holes in the ground left by looters—that the wider public began to grasp the scale of the systematic plundering of archaeological sites in the Middle East and Africa in the wake of the Arab Spring. Access to these images, which allow archaeologists to monitor sites in war-torn regions remotely, has become instrumental in the efforts to protect cultural heritage, particularly in conflict zones. This three-year project will train archaeologists from Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Libya, Occupied Palestinian Territories and Tunisia to use open-source aerial recording methodologies as well as geographic information systems. An additional £99,099 was awarded in July to expand the project to include archaeologists from Egypt, where looters have targeted sites such as Dashur and El Hibeh.

Image: courtesy of Turquoise Mountain

Murad Khani: £2,497,198

Efforts to revitalise the historic district of Murad Khani in the Old City of Kabul—a warren of streets filled with shops and houses—by encouraging entrepreneurial endeavours, promoting traditional Afghan crafts and traditions and making the preservation of its historic fabric a priority are key to this three-year project. It builds on various restoration and capacity-building initiatives begun in 2006 by the UK-based non-profit organisation, the Turquoise Mountain Trust. More than 1,350 locals are being trained in a variety of skills including traditional crafts such as woodworking and textile weaving, how to identify and document historic buildings, built heritage restoration techniques and traditional construction methods. “We’re already seeing statistics that show higher literacy rates in children that go to the schools where the artists’ families go,” Stenning says. Also part of the project is the restoration of five historic buildings and 45 shops.

Image courtesy Rum Kale

Rum Kale: £99,960

A team of experts is preparing to conduct the first archaeological survey of Rum Kale, an ancient fortified site on the Euphrates River in south-east Turkey. The two-year project will document the surviving buildings at the site, which served as an important religious centre for Christians in the Middle Ages before it was conquered by Muslims during the Crusades. A separate project to safeguard other archaeological sites in south-east Turkey through risk-management training initiatives received £923,660 from the Cultural Protection Fund.

REUTERS/Essam Al-Sudani

Basra Museum: £530,600

A shortage of funds meant that only one hall of the new Basra Museum was ready in time for its grand reopening in September 2016 in its new home in one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces. Looted during the Gulf Wars, the old Iraqi museum had been closed since 2003. The UK charity Friends of Basra Museum has teamed up with state antiquities departments in Basra and Baghdad to open the museum’s remaining three galleries, which will present artefacts from the Sumerian (3300-1792BC), Babylonian (1792-330BC) and Assyrian (883-612BC) periods that have been in store for 15 years. The project also involves training members of staff in museology and conservation practices. Training and the refurbishment of the galleries is due to begin in 2018. An additional £70,600 was awarded in September to “cover essential capital preparation work”.