Before the opening of Jimmie Durham’s retrospective at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in January, it was easy to predict that someone was going to raise serious doubts about the artist’s Cherokee ancestry and accuse him of being a “racial imposter”.

The issue, which has chased him for years, came up a decade ago when Anne Ellegood, a curator at the Hammer, began developing a joint proposal with Sam Durant and Durham for the US pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale. Durham quickly withdrew because he anticipated problems arising because he is not a registered member of a Cherokee nation.

While he told me in a rare interview for The New York Times this year that he is Cherokee by ancestry, he readily admitted that he and family members were never enrolled with a Cherokee tribe, describing his own opposition to registration on ethical grounds—“a tool of apartheid”, he called it.

When in June, Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World moved from the Hammer to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which was still reeling from tribal protests over Durant’s Scaffold sculpture, several Cherokee citizens published a joint letter denouncing Durham as a racial fake.

Collection of fluid archives, courtesy of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe

They argued that beyond his lack of registration, he had no knowledge of Cherokee traditions and “no ties to any Cherokee community”. One of the signatories, the artist and editor America Meredith, later cited research by a Cherokee genealogist and flatly concluded “Durham has no Cherokee ancestors”. They seemed to be building an argument, familiar from the attacks on Dana Schutz for her painting of the lynched black teenager Emmett Till when on show in New York at the Whitney Biennial, that the artist had no right to explore certain material.

I have a hard time stomaching these attempts at this sort of identity fundamentalism. A one-time student of comparative literature, I am partial to the argument that white men poaching or voicing experiences not their own has historically been a good thing that broadens a society’s worldview (think Huck Finn, Madame Bovary, and all of Shakespeare)—radical empathy as an instrument of artistic production.

Ellegood also published a persuasive defence of Durham and her decision to respect his self-identification as Cherokee. She challenged the binary—“he’s genuine or fake”—thinking as well as various gaps in his critics’ version of his family tree, calling it “incomplete and limited”.

But short of running a DNA sample for Durham (which thankfully nobody has proposed), this debate over his bloodline has stalled. I do not think any of us can with any certainty identify his ancestry.

We have all seen how juicy controversies over artists’ lives can eclipse their art, much as a headline sales price supplants any other sense of value

Which makes me think it is the right time to change the subject. What would it mean to discuss the integrity of his art—and its exploration of Native American cultural issues—independent of his authenticity as Cherokee? That is something I hope can be explored once his show opens at the Whitney next month (3 November-28 January 2018) and when it heads to the Remai Modern in Saskatoon, Canada, where more people will get to see the wild, woolly and deeply charismatic objects he has created over the years.

The artist Judy Chicago told me she was deeply moved by the exhibition at the Hammer because it seemed to embody Durham’s lived experience: “Jimmie Durham’s work is authentic, modest and funny. Plus he has the most uncanny sensitivity to materials. I’ve been interested in his work since the decades-old controversy about ‘true’ Indian art. What makes his work ‘true’ (with or without his being ‘registered’) is its combination of specificity and universality.”

And Durham’s work is both mute and riotous on the topic of his racial identity. Early on, he made works that took the form of Native American artefacts, creating entire pseudo-museological displays. But he worked to subvert the colonialist’s specimen-taking framework. Instead of featuring a comely Pocahontas headdress, for example, he displays her underwear: a garment he made of chicken feathers and dyed blood-red. His handprint from the same year has, according to the label, “real Indian blood” mixed into it. He is highlighting the bloodshed that is so often whitewashed from the founding history of the US.

And throughout his career he has either avoided self-portraiture or made a particularly evasive variety of it. Look for turquoise stones, recalling the artist’s blue eyes, showing up in unlikely places like animal skulls. Or often just one stone. (“Faces are not symmetrical,” he told me, “they only pretend to be.”)

Whitney Museum

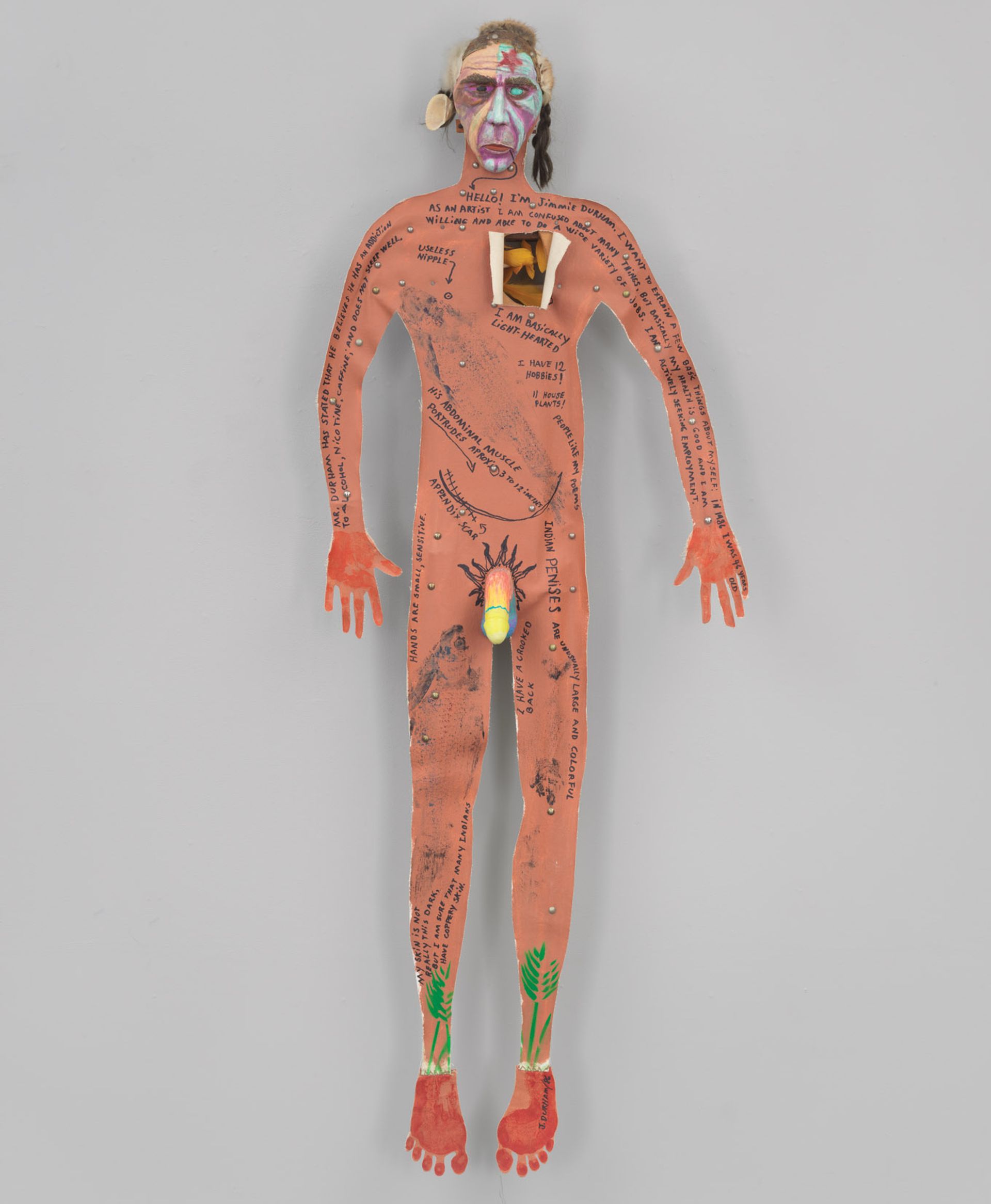

Or take his powerful and strangely self-deprecating Self Portrait (1986), in which he handwrites notes on a full-sized orange-painted canvas cut out. The notes point out his “useless nipple” and “appendix scar” among other odd attributes. “My skin is not really this dark, but I am sure that many Indians have coppery skin,” he writes along the right leg in a line that undermines the most basic convention of self-portraiture—the promise that it represents the self, not others.

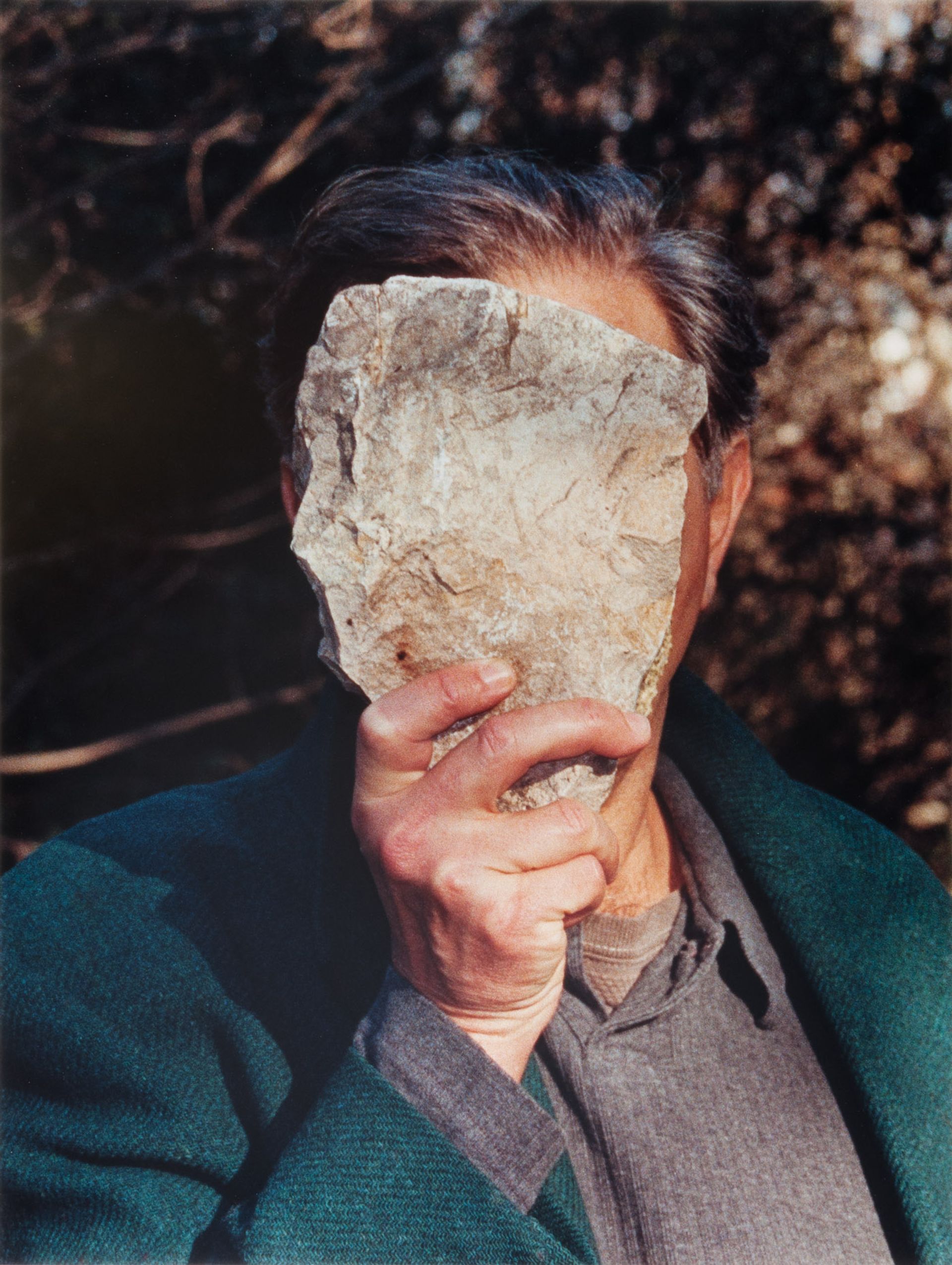

Then there is his series of photographic self-portraits from 2006 in which he assumes different guises. In one he places a flat, sharp stone, that looks like an oversized arrowhead in front of his face, and calls the work Self-Portrait Pretending to Be a Stone Statue of Myself.

A playful exploration of identity, this series could easily be read as a response to all his critics who label him a racial imposter. Here, in these works, he has become the trickster he has been accused of being. Unless, in a sly way, he is only pretending to be the trickster.

I am not saying his art supplies hard evidence for or against his status as Cherokee. Just the opposite: the work is exquisitely complicated.

We have all seen the way juicy controversies over artists’ lives can eclipse their art, much as a headline-making sales price supplants any other sense of value. Controversy hijacks what poetry critic Marjorie Perloff has famously called, with a nod to John Cage, “indeterminacy” in art. I hope visitors to Jimmie Durham’s show in New York and in Saskatoon will find their own ways to see past this scandal and rescue the poetry of his work.