A year ago, it looked like the seventh Moscow Bienniale of Contemporary Art was dead in the water, with no management, curator or venue. So it was a small miracle when the main exhibition,Clouds⇄Forests, opened at the New Tretyakov Gallery, the modern art branch of Russia’s main national art museum, on 19 September (until 18 January 2018). It is one of several biennials running across Russia this autumn.

The Japanese curator Yuko Hasegawa has brought a trio of big names to the Moscow show—Olafur Eliasson, Matthew Barney and Björk—as part of the concept of “creative tribes” that overcome the divisions of nation states. The biennial has been greeted with mixed reviews as an event with little international impact. However, the Moscow premiere of Björk Digital, the Icelandic singer’s immersive virtual-reality installation, does fit with the Tretyakov’s agenda of attracting young Russians—on a recent Saturday evening, the average age of visitors to the museum appeared to be under 20.

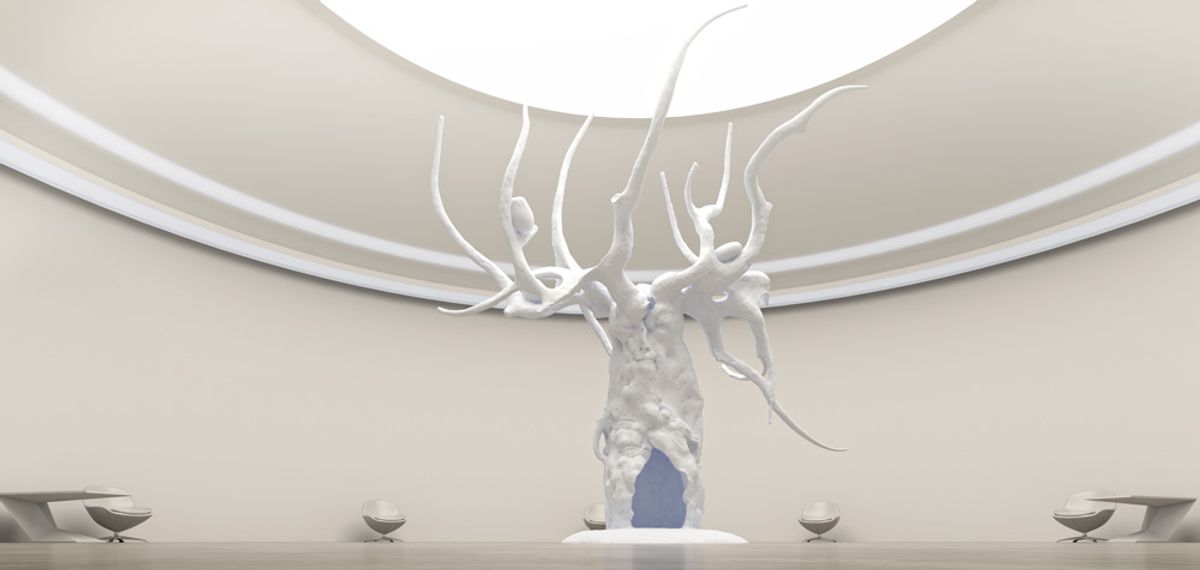

Although the biennial is also meant as a platform for Russian contemporary artists, the entrance is dominated by a monumental sculpture by Dashi Namdakov, an established sculptor known for commissions by Russia’s Kremlin and business elite. “Guardian of Baikal” pays homage to the Buryat artist’s nomad and shaman heritage and his connection to the world’s largest freshwater lake in Siberia. The 7.5-metre-high bronze was meant to be installed on Lake Baikal’s Olkhon Island during the biennial, with a smaller plaster copy at the New Tretyakov that visitors could view with virtual-reality (VR) goggles as a high-tech complement. Environmental concerns scuttled the Baikal version, but biennial visitors can still don a VR headset for a slightly dizzying and rather breathtaking journey to the lake.

Mikhail Piotrovsky, the director of St Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum, was a guest speaker on 30 September to discuss the interaction between classical and contemporary art. The Hermitage hosted Manifesta, the roving European contemporary art biennial in 2014, and recently exhibited works by the Belgian artist Jan Fabre among Flemish Old Masters in the Winter Palace. But Piotrovsky’s most striking revelation was that the Hermitage had not been planning to mark the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution—even though the Winter Palace, former residence of the czars—was a central player.

“Our Dutch colleagues at the Hermitage Amsterdam asked us, ‘What will we be doing for October?’ We said, ‘Nothing much’,” Piotrovsky said. “They said, ‘Are you crazy? The whole world is waiting. Something needs to be done’.” The Hermitage is, of course, marking the event, with two exhibitions: The Winter Palace and the Hermitage in 1917 (26 October-4 February 2018) and The Press and the Revolution: Publications 1917-1922 from the Hermitage Collections (26 October-14 January 2018).

Other Russian biennals now on

4th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art

Yekaterinburg has become one of Russia’s centres of contemporary art, bolstered by its Constructivist heritage, which helps draw international participants to the biennial (until 12 November). This year’s main project, which has as its curator João Ribas, the deputy director and senior curator of the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, is titled New Literacy and examines how the “fourth industrial revolution” of information and communication technology is changing society.

9th Vladivostok International Biennale of Visual Arts (VIBVA)

The biennial of Russia’s Pacific gateway has come back after a four-year hiatus, and given its location on Russia’s eastern seaboard, not surprisingly with a view to the East (until 20 October). Xiang Liping, a former curator and co-ordinator of the Shanghai Biennale, is curator of the main project, Port Morphology: Rules of the Game.

12thKrasnoyarsk Museum Biennale

Simon Mraz, Austria’s cultural attache and the director of the Austrian Cultural Forum Moscow, has spent two years developing plans to mark the Revolution. His exhibition, Mir: the Village and the World forms the centrepiece of the Krasnoyarsk Museum Biennale, Russia’s longest-running contemporary art biennal—this is the 12th edition—(until 28 February 2018). “Mir”, in this case, refers to an arcane understanding of the word, which usually means peace, as a name for the Russian village community.