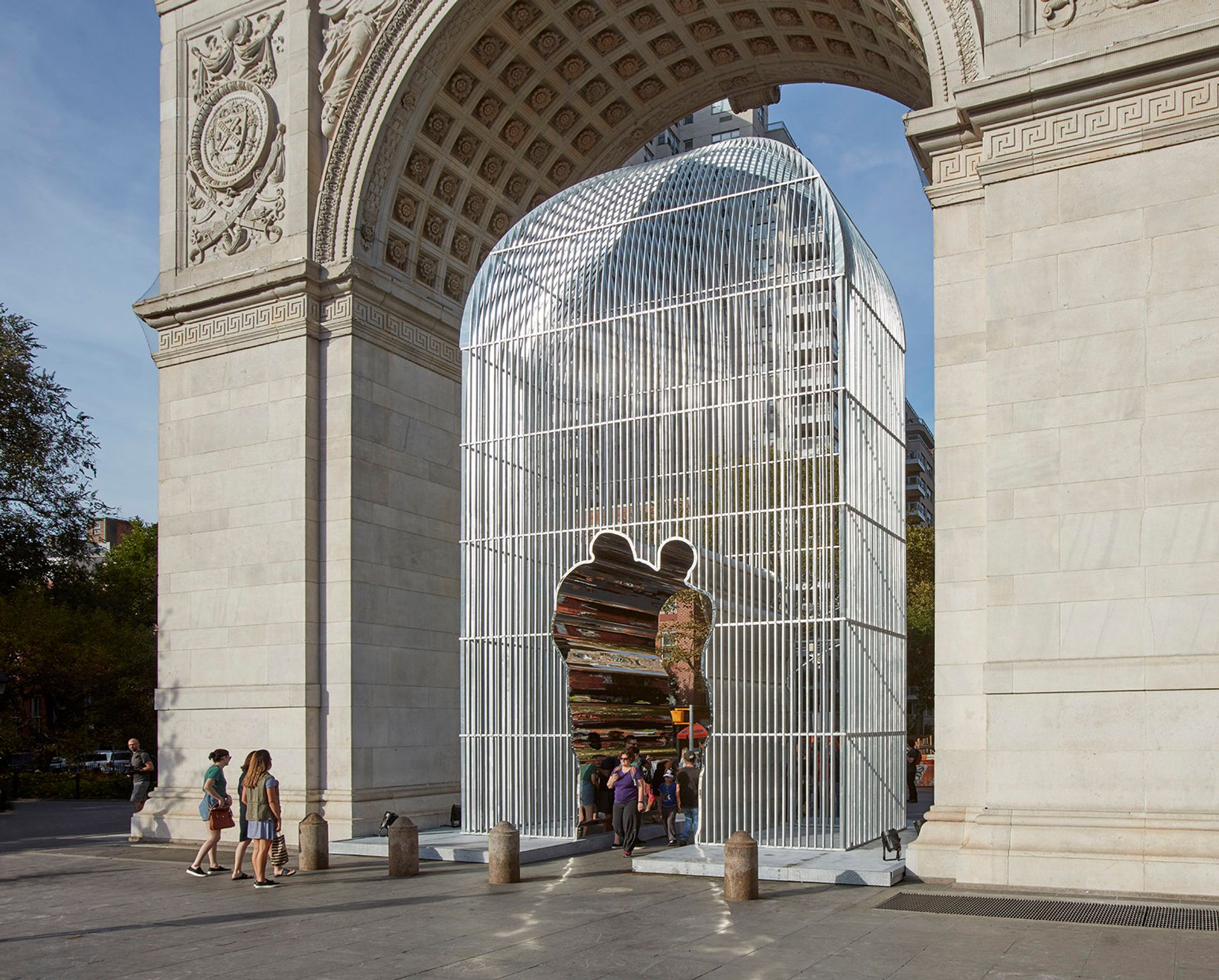

“When you have a president who calls people criminals and rapists, which is quite shocking, fences can be a reminder to consider others,” said the Chinese artist-activist Ai Weiwei during a talk at the Cooper Union Thursday night (12 October). Speaking with Nicholas Baume, the chief curator and director of the Public Art Fund, the artist was discussing his multi-site project in New York, Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, which opened to the public yesterday and runs until 11 February 2018. The commission addresses ideas around borders, immigration and the refugee crisis, and includes 300 works—in the form of wire fences, large-scale steel sculptures, and images of refugees—installed in public, commercial and residential spaces across the five boroughs.

Some works have been mounted on bus stops, flagpoles and in the gaps between buildings, while 18 monumental sculptures can be found in Washington Square Park, the Doris C. Freedman Plaza of Central Park and Flushing Meadows Corona Park, among other open spaces. At the Cooper Union, the artist installed metal bars on five colossal windows of the school’s science and arts building and hinted that he might permanently donate the installation to the school.

Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio/ Frahm & Frahm. Photo: Jason Wyche, Courtesy Public Art Fund, NY

Weiwei’s framework for the project comes from his humanitarian work in refugee camps in Syria and Greece, where he documented the communities disparaged by political crisis and the fences that separate them from larger society. His debut film on the issue, called Human Flow, is now in theaters.

Weiwei posted various photographs of the fences he saw in refugee camps on Instagram, which can be seen as the drawing board for the project. “When I think of public art, I think of social media and the Internet, which is so much easier than doing something physical”, Weiwei said. The free-standing works in the commission aim to “be minimal and not necessarily act as a work of art but something that just makes the people feel and think differently—something that maybe makes people consider those on the other side of the fence”.

The artist said that the social stratification that fences create is something he also relates to his own experience as a Chinese immigrant in New York in the 1980s. Ai, who studied at Parsons, said that “my school experience was very short—I dropped out after half a year for no other reason than I couldn’t afford the tuition”. He later worked as a street portraitist, he added, creating works for $15 that were “just as good as Matisse or Picasso”. Of the reason why the city continues to appeal to artists, Ai said: “New York has a lot of super rich people, there’s danger, there’s tension, but it’s so attractive because of the power and the opportunities that are here”.