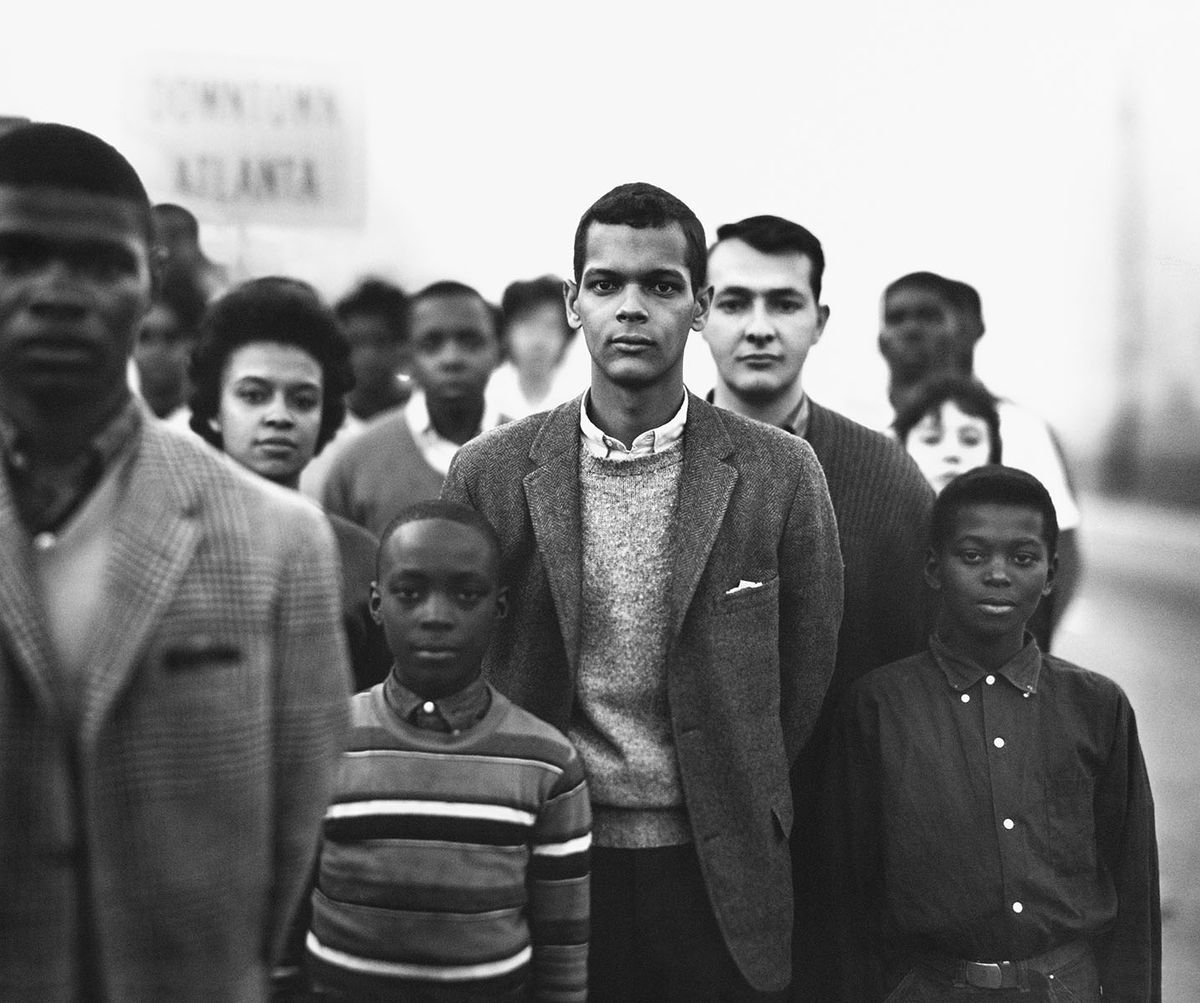

This November, a little known collaboration between the photographer Richard Avedon and the writer James Baldwin could find new resonance in the current political climate. Pace and Pace/MacGill gallery in New York will mount an exhibition of works from Nothing Personal, a book the two produced together in the early 1960s that aimed to be a critical look at American identity and society. The publisher Taschen is also reissuing the title with a new introduction by the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Hilton Als.

Avedon, best known for shooting fashion editorials for Vogue, and Baldwin, who wrote about social issues related to race in searing works like Notes from a Native Son, may seem like an unlikely pair, but they were long-time friends. In the late 1930s, they attended DeWitt High School in the Bronx, where they co-edited the school’s literary journal, The Magpie. Shortly after Avedon photographed Baldwin for a magazine in 1963, the two began to plan a book of photographs and texts, which Baldwin would ultimately characterise as an examination of “some national and contemporary phenomena in an attempt to discover why we live the way we do”.

The exhibition, Richard Avedon: Nothing Personal (12 November-13 January 2018, at Pace's 24th Street location), charts the formation of the project, combining the photographer’s black-and-white portraits with the writer’s reflections on American identity and despair. A rebuke of post-war optimism, the book was widely panned by critics as “exploitive” and the work of mere “show-biz moralists” on its publication in 1964. Part of this was due to the book’s glossy, luxe presentation clashing with its intended cultural criticism. Pace/MacGill director Peter MacGill, who was close with Avedon, says critics had a hostile reaction because “they resented the fact that here was a well-known fashion photographer out there photographing the stuff of life”.

Each man’s contributions to the book interact in subtle, indirect ways. Baldwin’s four-part essay, written on the heels of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, bemoans a “loveless nation”, its fraught relationship to the past, and pleads for greater fellow feeling. Avedon, meanwhile, offers a curious gallery of people and faces: the actress Marylin Monroe; George Lincoln Rockwell, the commander of the American Nazi Party; patients of a mental institution; a group portrait of the Daughters of the American Revolution; and William Casby, a former slave. MacGill says of the book’s complicated structure: “It’s like a fugue. It’s not a simple melody that you can whistle down the street.”

Gathering nearly every photograph from the book, the show will be supplemented with archival materials, such as letters, pages from the photographer’s diaries—an entry, for example, from the day that he photographed three generations of the Martin Luther King family—and snapshots of Avedon and Baldwin together as teenagers. One notable document is a letter from Dwight D. Eisenhower’s assistant, who informs Avedon that he may not reproduce his photograph of the former president in the book. Avedon replied that, sorry, it was already out to press.