Judy Chicago is poised to make another comeback. With a dedication that few artists can match, she has been steadily making art and increasingly working on preserving her legacy, despite wild fluctuations in public opinion and critical reception. This autumn, her work will be especially prominent, with her early output presented in a new light. The gallerist Jessica Silverman has organised Chicago’s first major show in San Francisco (until 28 October), called Judy Chicago’s Pussies, with a nod to her pioneering vaginal imagery and more recent cat portraiture. Two new museum shows explore the creation in the mid-1970s of her installation masterpiece The Dinner Party: the Brooklyn Museum’s Roots of The Dinner Party: History in the Making (20 October-4 March) and Inside the Dinner Party Studio at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, DC (until 5 January). Chicago is also preparing for a new monograph from the publisher Scala with NMWA, and the digitisation of her archives by the different institutions in which they reside, both two years away.

Judy Chicago

The Art Newspaper: What do you think visitors will learn about The Dinner Party from the Brooklyn or NMWA show that they didn’t already know?

Judy Chicago: The show in Brooklyn is the first ever to look at my creative process, starting with my research and going into how I transformed historical information into images. People say that I brought china painting and needlework into high art, but what does that actually mean? [The curator] Carmen Hermo is going to trace the creation of the Mary Wollstonecraft and Sojourner Truth place settings, and step back to look into the two years it took me to bring china painting over from the hobbyist tradition. You will see my china painted test plates, my bringing the techniques together with my imagery, and the process of raising the plates. And then the NMWA show, which is more modest, will be set up like my ceramics studio in Santa Monica was. I’m hoping people will begin to understand my practice as an artist, and my commitment to research and learning new techniques to figure out what is appropriate for the subject matter.

I was trying to create a symbolic history of women in Western civilisation

What are the biggest misconceptions about The Dinner Party?

One is about the nature of the collaboration. The concept of The Dinner Party was mine, the images were mine and the final aesthetic decision on everything was mine. But within that structure, because it was such a big project and because I was trying to create a symbolic history of women in Western civilisation, there was plenty of room for people to introduce their own ideas. That’s one reason why so many people volunteered—they were able to learn women’s history and join reading or consciousness-raising sessions. Until the late 19th century, women artists did not have access to the same level of training as men; they were never part of the apprentice system. I wanted to make that available to women. Something else people don’t understand: there was such a range of participation, from full-time workers to someone who stitched a single flower and sent it to the studio. Brooklyn owns the acknowledgment panels that originally travelled with the show, but they’ve never hung them. They will now.

Judy Chicago

You now have two women dealers, Jessica Silverman and Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn of Salon 94. How important is it to you to have women representing you?

I’ve had women dealers before but I’ve never had dealers like this before. Both of my galleries have taken a tremendous load off my shoulders: all my business stuff, all the loans, the exhibition and book planning. I did all of this myself before—I had to or I wouldn’t have had a career.

I heard you optioned your autobiography Through the Flower to Jill Soloway, the creator of the Amazon TV series Transparent. What’s the status of that now?

This is straight from Jill by email: “The writer is just finishing up her second draft of the script, which is going really well.” They’re planning to have it with Amazon in October. I don’t know her focus for sure because I haven’t read a script yet. But what I understand is they are working on a limited series about the early part of my career. I think they’re interested in Fresno, Womanhouse [her feminist education projects, see biography], my struggle as a woman artist.

Judy Chicago, photograph courtesy of Megan Schultz

Mira Schor, a participant in Womanhouse, wrote a blog reacting to the news of your option, calling you a divisive figure within feminism since the 1980s, instead of someone who has advanced the movement over that time. What’s your response to that?

That’s very hurtful.

What do you think of Jill Soloway and her work?

I thought the second season of Transparent was incredible. I was so blown away that Jill Soloway could educate, illuminate and entertain an audience with this history of the Weimar Republic that is so important to the LGBTQ community. I thought it was un-fucking-believable. And that’s why I said: “Jill, I’m going to trust my history in your hands.” When we spoke on the phone, I felt like I was hearing my younger self. [The writer] Anaïs Nin, my mentor, used to call me her radical daughter. That’s kind of how I feel about Jill.

Anaïs Nin, my mentor, used to call me her radical daughter. That’s kind of how I feel about Jill Soloway.

The art division of United Talent Agency, run by Joshua Roth, handled the Soloway option. Are you working with them on anything else?

Lesley Silverman [Jessica Silverman’s sister], who represents me at UTA, we’re producing a whole new line of products for the Roots show in Brooklyn. There will be a goddess-shaped soap in a bright pink box, a line of eight place mats based on Dinner Party placements, produced by [department store group] Barneys, and a Through the Flower scarf that looks just like that painting.

You called your show at Jessica Silverman, which brings together your sexual imagery and feline portraiture, Judy Chicago’s Pussies. That must have felt good to say?

You couldn’t use that word in the 1960s in LA—that’s what the Ferus boys [artists associated with the Ferus Gallery] used to call each other to put each other down. Now there are Instagram sites that I love: Vagina China and Club Clitoris. I saw a T-shirt that said: “Eat pussy, not animals”. [Laughs] You just couldn’t say that; it was totally taboo when I was young, so I love it. Jessica is a great curator, so in my Pussies show there will be a broad array, from work from the 1960s up to Kitty City. It’s a series of watercolours based on a medieval book of hours but instead of being devoted to God it’s devoted to our lives with cats.

You also did a series of watercolours, called Caterotica, showing a cat licking and nipping a woman in all the right places.

The first time I showed it, this woman came up to me at the opening and said: “Where do you get a cat like that?” [Laughs] I had to tell her I made it up.

Three Key Works

Judy Chicago

Birth Hood(1965/2011)

Early on, Chicago tried to match the swagger of the men who dominated the art scene in LA. But her true colours, as she describes them, kept surfacing. So even when she went to auto-body school in the 1960s to learn spray-painting skills, the resulting work, Birth Hood—painted on a car hood, or bonnet—was criticised for its oversexed imagery and garish or girlish palette. (“I just liked pinks and turquoises and chartreuse and ivory. You should see my sneakers,” she says.) Now, this work is considered an important early phase in her career, connecting her to California artists who worked with plastics or industrial materials, such as DeWain Valentine and Robert Irwin.

Amy Meadow. Image courtesy: NMWA

The Dinner Party(1974-79)

Her most popular and also controversial work, seen as vulgar by some contemporary critics, this massive installation features 39 place settings with porcelain plates and embroidered runners, each paying tribute to a powerful woman in history. Vaginal imagery abounds. The banquet, created with the assistance of numerous volunteers (above), travelled across three continents to reach more than a million viewers before it was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 2002.

Judy Chicago

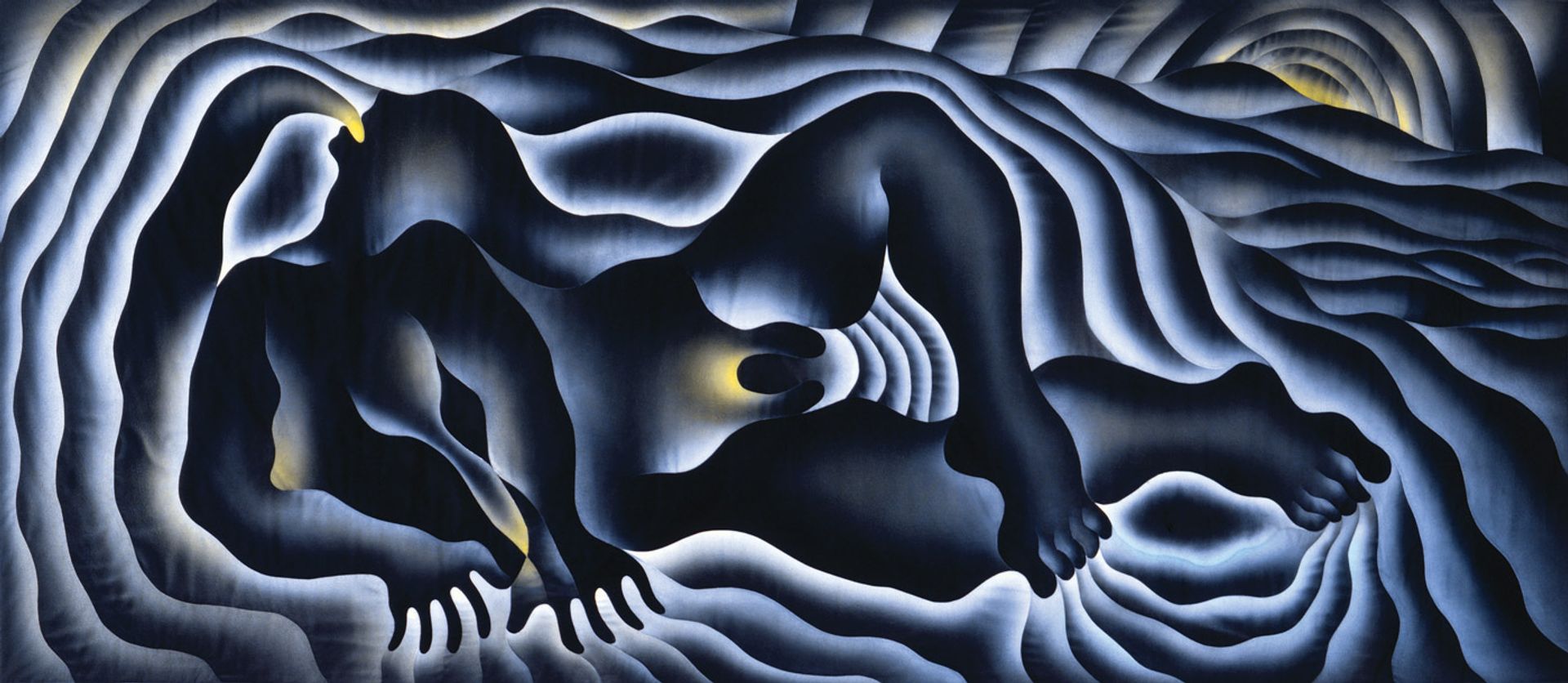

Earth Birth(1983), from The Birth Project(1980-85)

For her biggest orchestration of different talents since The Dinner Party, Chicago reached out to 150 needlepoint workers in the US, Canada and New Zealand to help her visualise accounts she had gathered (and, in some instances, witnessed) of women giving birth. “I have tried to express what I’ve seen—the glory and horror of the birth experience itself, the joy and pain of pregnancy, the sense of entrapment that goes along with the satisfactions of giving life.” Today the series remains striking for her fluidity in mixing mediums such as paint and fabric and for its graphic appeal, including high-voltage backgrounds that make Keith Haring look derivative.

Biography: Judy Chicago

Background and Education: Born in Chicago in 1939, Judy Cohen, as she was then known, showed an early talent for drawing and was taking classes at the Art Institute by the age of five. She received her BA from theUniversity of California, Los Angeles in 1962 and completed her MA there in 1964. She says that Judy Chicago was her “underground name” before she made it official in 1970, following the death of her first husband. Nicknames, she explains, were common among LA artists in the 1960s. “Larry Bell was Ben Lux, Ed Ruscha was Eddie Russia. It was an in-thing to do in the small burgeoning LA art scene—we all listed our underground names in the phone directory. If you really knew us, you knew how to find us.”

Milestones: In the 1960s, Chicago made a colourful sort of Minimalism and was one of only three women included in one of the movement’s most important shows, Primary Structures, at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1966. In 1970, she started the first feminist art programme at Fresno State College, before establishing a similar programme at the California Institute of the Arts with Miriam Schapiro the following year. Because the campus was still under construction, the two soon turned a run-down house in Hollywood into Womanhouse, an art performance and installation space. Her first major work, The Dinner Party (see above), debuted at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art before travelling to many offbeat venues—other big museums at the time would not touch it. More recent projects, also intensive in nature, have taken on such subjects as giving birth (see Earth Birth, above) and the Holocaust (her 1985-93 collaboration with her husband Donald Woodman). Her use of media has varied, with painting remaining one constant and an impulse for narration or storytelling another.