Ralph Rugoff, the curator of this year’s talks programme at Frieze London, hopes that there will be moments “when the audience isn’t sure exactly what kind of event they are attending”. The programme is loosely themed around the idea of “alternative facts”. Alongside panel discussions earlier this week on Alt-Feminisms, chaired by the curator Alison Gingeras, and a “performance-conversation” between the artists and long-term collaborators Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Philippe Parreno, are Sunday’s events that include the “sung lectures” of Nástio Mosquito and Mx Justin Vivian Bond and a discussion on how to engage with fake news led by the writer Angela Nagle.

Rugoff says that “the general impulse behind the programme is to pose a question: given that artifice and scepticism have traditionally been associated with art and artists, what happens to the role of the artist when those tools are appropriated by government and corporate agencies, right-wing news groups and climate change deniers, etc?”

Art and artifice

Outside of Rugoff’s programme, many artists are addressing the fake news phenomenon head on, appropriating and subverting online materials and strategies. Often the approach is implicitly rather than overtly critical. The artist Amalia Ulman enjoys “playing with fiction”, as she put it in an interview last year, both online and in the form of installations in galleries. On Instagram in 2016, she suggested she was pregnant, but when it emerged that this was a performance, there were indignant responses. Ulman says that “people get really upset when they’re not told the truth online. But that never happens anyway; no one is ever really telling the truth there.”

She notes the difference between responses to online works and other media. “If you look at a painting of a pregnant woman, you’re not thinking, ‘Was she pregnant for real? What happened to the baby?’ That’s not the point. You’re looking at the painting and the composition and how it makes you feel, or whatever.”

As part of that same work, Ulman delved into the murky online world of white nationalism, the self-styled “alt-right”, whose memes and hate speech, largely unpoliced online, have been a crucial element of Donald Trump’s armoury. Ulman was “interested in the alt-right and the aesthetics they use to communicate”, she says. She spotted that underlying it all was their frequently expressed idea that they were speaking common sense. “But they really use it to construct their own truths,” she says. “And that’s what Trump does: he constructs his own truths and people listen to him and think it makes sense. Because, of course, you can construct your own commonsensical argument according to what is convenient to you.”

Making myths

Zardulu the Mythmaker is a New York-based performance artist who has created photographs and videos that have become viral sensations—a rat taking a selfie on the New York subway; a three-eyed catfish caught in the Gowanus Canal. The work takes effect not just in the delighted or bemused sharing of the material, but in the serious commentary that follows it: the New York Times did a lengthy piece on the Gowanus story, interviewing a biology professor and an environmental scientist, among others.

Zardulu argues that “we’ve come to a point where our collective unconscious has begun to turn away from realism and rationality. Deep down, we don’t care about the truth. We want myth. We want our feelings and emotions to be represented in symbolic forms. That might be from seeing one of my fabricated news stories or it might be from a radical right-wing newscaster telling their modern myth, their fairytale.”

Zardulu cites André Breton’s surrealist theories “mixing the fantasies of the artist with reality” as an influence and found that online was a natural arena for her work: if she “blended my fantasies into reality for an unknowing audience, it would be a true ‘sur-reality’. So, I did things like put a raccoon on an alligator and photograph it in the swamp. It was published by National Geographic, seen by tens of millions of people all over the world.”

She sees herself as a modern equivalent of Hermes, the “divine trickster” of the ancient gods. “A world without tricksters is without possibility,” she says. “It is forever unchanging. It is lifeless. Duchamp was a trickster, the trickster the art world needed at the time. He possessed what I see in all tricksters—a disruptive imagination. It’s different than simply being an artist.”

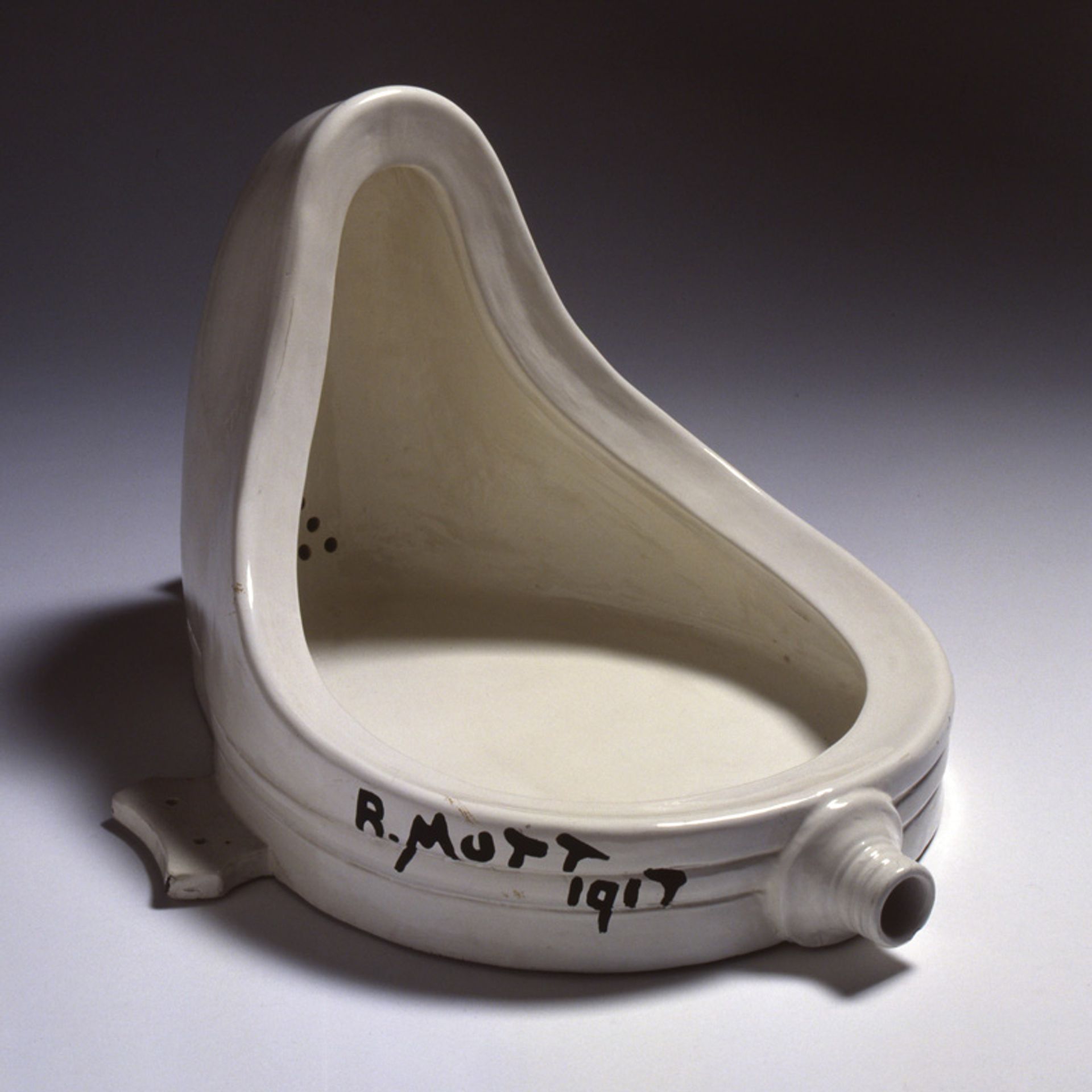

Indeed, the history of Fountain (1917), Duchamp’s upturned urinal, currently on show in London as part of Dalí/Duchamp at the Royal Academy (RA, 7 October—3 January 2018), is emblematic of Rugoff’s idea of “artifice and scepticism” being the preserve of artists. “It was a great game he was playing with official supporters of Modern art in New York, who had just founded this major exhibition called The Independents [the Society of Independent Artists],” says Dawn Ades, the curator of the RA exhibition. Duchamp was on the committee yet subverted his role by anonymously submitting the urinal, signed by R Mutt, which was rejected by other members of the committee. He resigned and, working with a team of people, orchestrated the avant-garde outrage around its rejection and its interpretation as a “new thought for the object” (see sidebar).

It was one of a series of Duchamp’s deceptions and role plays. At one point, he adopted a female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy. “His first idea was to become Jewish, but then decided that wasn’t such a good idea, he’d become a woman instead,” Ades says. “So he invented Rose Sélavy and then he added the double R, so it was Rrose Sélavy. You pronounce it as ‘Éros, c’est la vie’—Éros, that’s life.”

Duchamp dressed up as Rrose and was photographed by Man Ray. “One can’t overlook the role of photography itself in this, because the photograph is meant to tell you the truth, and that is the other thing that Duchamp was wonderful at, playing with this pretension of photography to tell the truth about the world. With a photograph, he could change identity. And Rrose signed things, too; she did operate as an artist.”

Duchamp’s games were his response to his feeling that “modern painting had become too ‘retinal’”, Ades says. “He felt that painting only appealed to the eye and he wanted to reintroduce what he called a bit of grey matter.”

It seems likely that the culture of alternative facts will occupy the grey matter of today’s artists for some time to come.

Duchamp’s Fountain: a truly elaborate deception

Photo: © Schiavinotto Giuseppe

Dawn Ades, the curator of Dalí/Duchamp at the Royal Academy, describes the French-American artist’s elaborate deception with the work Fountain (1917).

“The Independents exhibition was intended to be a jury-less show, so anybody who paid six dollars could send in a work. Duchamp was on the committee for the exhibition. It was his idea that the whole thing should be hung alphabetically by artist’s name—it was very funny.

“So this urinal arrived with a label on it and the name R Mutt. I’m sure it was Duchamp’s idea, but he got other people involved and the person who actually sent in the Fountain physically was his friend Louise Norton; it was her phone number on the label. It was then rejected by the committee. Duchamp immediately resigned, although he didn’t reveal that he had been behind the whole game.

“The work was put behind a curtain and was never on show. Duchamp and some friends took it to Alfred Stieglitz’s photographic studio and had Stieglitz photograph it. It was then reproduced in the little magazine that Duchamp edited together with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood called the Blind Man. The person who wrote a little anonymous text, it seems, was Wood, who expressed the notion that whoever this was, this R Mutt, had created ‘a new thought for the object’, that the object was not plagiarism and it wasn’t pornographic.

“The other text was by Louise Norton, a lovely text called Buddha of the Bathroom, picking out the fact that Stieglitz had photographed Fountain so that the outline looked rather like a Buddha, or indeed a Madonna.

Duchamp didn’t actually reveal that he was behind the whole thing for some time.”

• Frieze London Talk, Asocial Media (with Ed Fornieles, Constant Dullaart and Angela Nagle), Sunday 8 October, 12.30pm

• Frieze London Talk, The Singling Lecture (with Nástio Mosquito and Mx Justin Vivian Bond), Sunday 8 October, 4.30pm