In the summer of 1975, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark sneaked into an abandoned warehouse shed on Pier 52 in Manhattan’s far west side and created the work Day’s End. Cutting holes into the walls and ceiling to let in the sun, and a trench through the floor that opened onto the river, Matta-Clark envisioned the piece as a space for the New York public to gather, a “temple” of light and water. But since the artist did all the work illicitly, police shut down the opening, a warrant was put out for Matta-Clark’s arrest and the city even filed a million-dollar lawsuit, although the claims were eventually dropped. So, aside from the young men of Chelsea’s gay scene who used the pier as a sunbathing spot and others who slipped into the warehouse surreptitiously, Day’s End never became the grand cultural nexus Matta-Clark hoped, and it was later demolished by the city.

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y.

Now, the Whitney Museum and the artist David Hammons hope to pay tribute to Matta-Clark’s vision, as well as the Meatpacking District’s history, with a new public art proposal that was unveiled at a local community board meeting Wednesday night. Also titled Day’s End, as an homage to the original, the piece is a skeletal framework of the warehouse shed built from stainless steel poles anchored to the riverbed and the riprap of the adjacent Gansevoort Peninsula, which is due to be turned into a public park once the Sanitation Department moves out. The work seems to float above the river and its overall appearance shifts based on the weather and the time of day.

You have a sense that this is something that was always there… yet it sort of disappears a little bit

During his impassioned presentation to the community, the Whitney’s director Adam Weinberg called the sculpture “a kind of ghost monument” and “a drawing in space that has an evanescent quality”, comparing it to Calder’s work currently on view in the museum. “You have a sense that this is something that was always there… yet it sort of disappears a little bit.”

He also drew on the site’s long history and the changes it has undergone over the centuries—from its early days as an Algonquin fishing settlement to its heyday as a shipping pier—as something that could be referenced in didactic materials related to the sculpture, like a mobile app, a documentary and oral histories with locals. “It’s not just about what’s here, but what’s gone,” Weinberg said.

Weinberg also gave a concise but emphatic summary of Hammons’s work and practice—as well as his stark independence, especially from the art market—aiming to convey what a rare opportunity this permanent public art piece, by one of America’s most important living artists, would be.

David Hammons

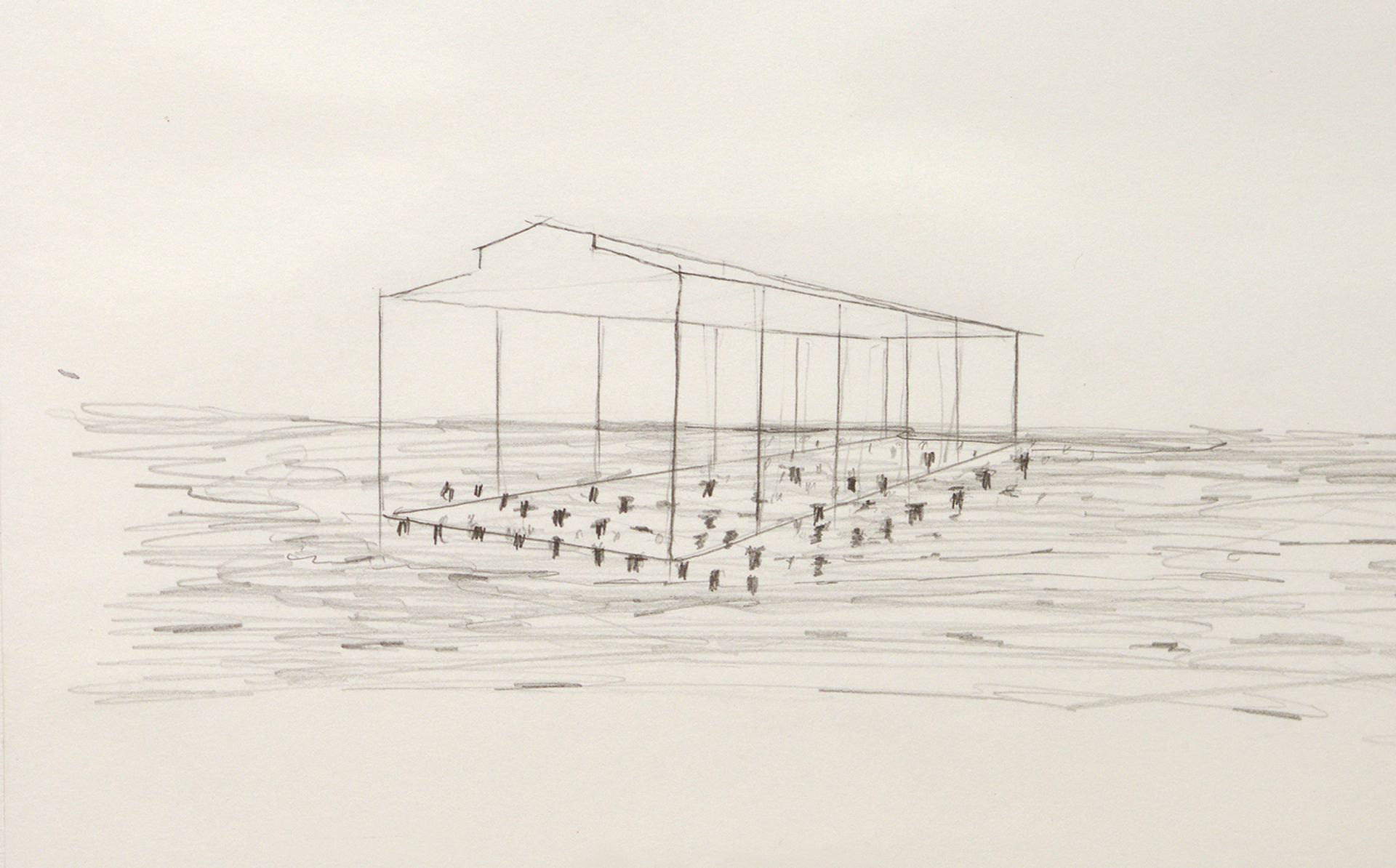

In fact, the idea for the sculpture came from Hammons himself, during a visit to the Whitney while its new home was still under construction. Invited to view the museum’s massive fifth floor galleries, where the Whitney organised its Open Plan series of solo artist shows last year, Hammons instead was drawn to the view outside the floor-to-ceiling windows, where Weinberg explained Matta-Clark had created Day’s End. A few days later, the museum received a sketch from Hammons, showing a floating structure on the water. “Is this a provocation? Is it a proposal? Is it a gift?” Weinberg remembered asking about the drawing. A follow up with the artist’s studio led to a feasibility study over the past year with the engineer Guy Nordenson to determine what it would take to make the sculpture a reality.

More work still needs to be done to finalise the cost of the construction, which the Whitney will raise privately and Weinberg admitted is “not cheap”, and the ecological impact has yet to be fully determined. But Weinberg said during the meeting that it was important to the museum that the community hear about the proposal first (although the story leaked to the New York Times two weeks ago, as a result of the scrapping of developer Barry Diller’s planned Pier 55 project nearby), and he was attentive and receptive to the many concerns and questions voiced by the public. “We didn’t want to promise you a project and then say we can’t build, we can’t afford it—we also don’t want to raise your hackles if you don’t want it.”

Courtesy Guy Nordenson and Associates

The initial reaction from the community seemed to be positive and the community board later unanimously voted to approve the project. Vincent Inconiglios, a resident of the neighbourhood since the 1960s, called it “a spiritual resurrection” and Florent Morellet, the former restaurateur said, “I love this project”. Matta-Clark’s widow Jane Crawford, who also attended the meeting, said she “couldn’t imagine anything more poetic” than Hammons’s tribute. However, one long-time resident of Jane Street, who wanted to remain anonymous, said her concerns about trash collecting around the sculptures piles weren’t satisfactorily answered, and that a full environmental impact study by the US Army Corps of Engineers should be done.

In his closing words during Wednesday’s presentation, Weinberg acknowledged that there was a long road ahead: “This is the beginning of a conversation, not the end of one.”