Dealers and auction houses are scrambling to find top paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat to meet the surge in interest in the late artist’s work, following the record $100.5m auction of his untitled skull painting at Sotheby’s New York in May.

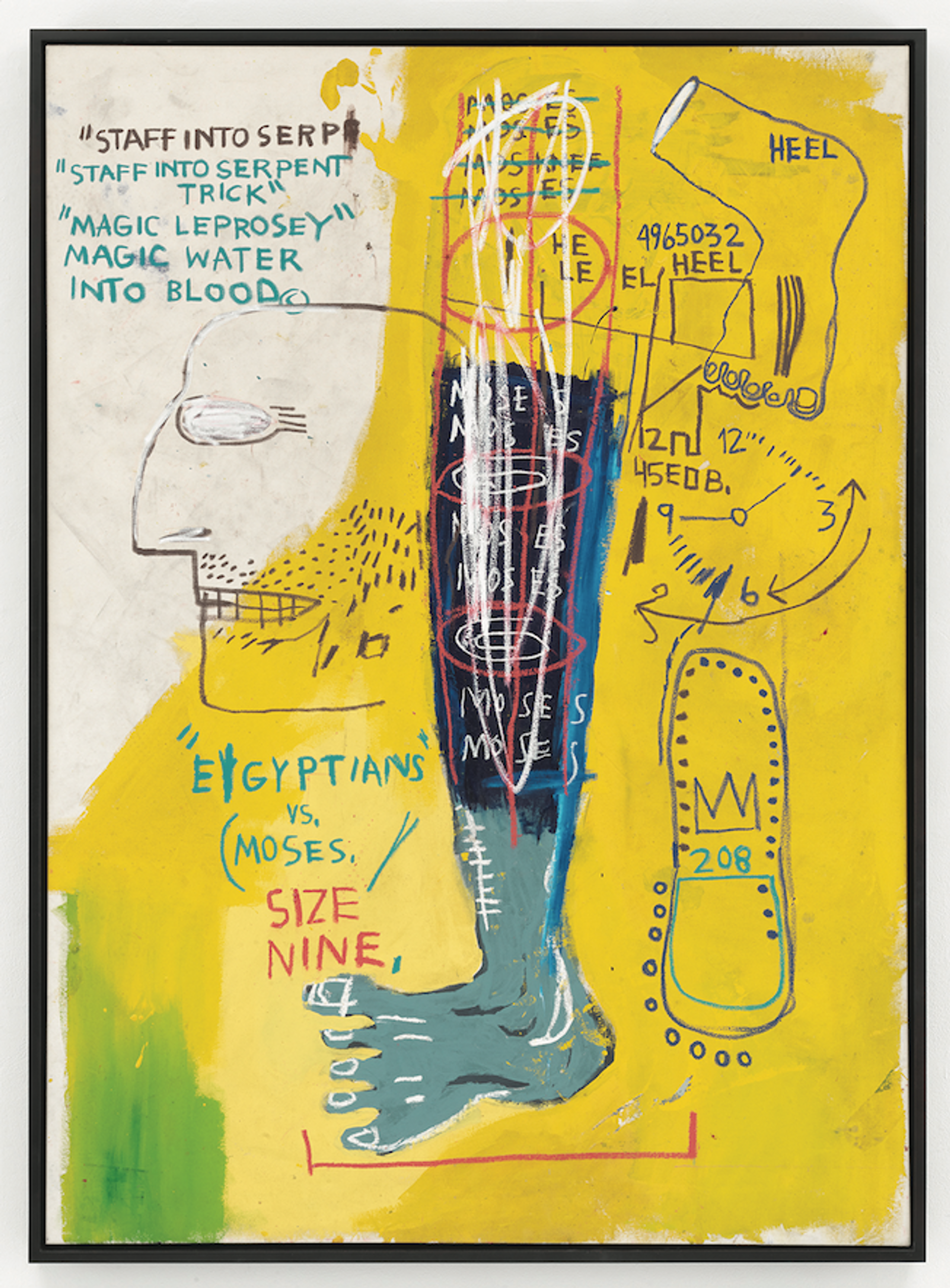

The sale, to the former Japanese rock star turned e-commerce entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa, has “significantly increased demand for Basquiat”, says Joe Nahmad of Nahmad Contemporary, which is offering a yellow canvas with anatomical renderings and text entitled Early Moses (1983) for $8.5m at Frieze Masters. “I’m getting more requests for Basquiat than I’ve ever had before,” he adds. The interest is coming from the US and Europe, but also from collectors in Asia, South America and the Middle East. “New collectors who want to buy their first major painting are looking for Basquiat.”

The artist’s bold, brightly coloured canvases, which merge elements of street art, popular culture and disparate other sources, resonate with younger generations. Basquiat has been embraced by the most influential musicians of our time, as well as taste-makers on social media. “I’m the new Jean-Michel,” declared hip-hop mogul Jay-Z in his single Picasso Baby, while Maezawa announced his $100.5m purchase on Instagram.

A strong part of the appeal is the myth of the destitute, self-made street artist who found fame through sheer talent and force of will. This version of Basquiat’s life overlooks the fact that he came from a well-off family: his father was an accountant, born in Haiti, and his mother was of Puerto Rican descent. The artist had an expensive private education and was trilingual in English, Spanish and French from the age of four.

It’s all about 1982

Works from 1981 and 1982 are particularly prized by the market: the top ten auction prices for the artist are for paintings from those two years. It was in the early 1980s that Basquiat transitioned from being a graffiti artist to a studio-based one.

“He was given space by the gallerist Annina Nosei and was able to create fully realised canvases with the same intensity and vitality as his street art,” says Katharine Arnold, the director and senior specialist in charge of post-war and contemporary art at Christie’s, which is offering the artist’s Red Skull (1982) in its evening sale this Friday 6 October. The work has a low estimate “in the region of £12m”, according to the auction house. (Proceeds from the sale will go to KIPP schools in New Jersey, a network of free, public charter schools with no entrance requirements and a record of high performance).

Courtesy of Christie's

“Red Skull still bears the image of the streets, with the Brooklyn Heights buildings visible in the upper right, rendered in thick black oil stick… and has the immediacy of graffiti,” Arnold says.

After 1983, Basquiat “became a very serious addict”, says Emily Tsingou, the London art adviser who bought his painting La Hara (1981) for $34.98m (with auction house commission) for a client at Christie’s New York in May. Just five years later, in 1988, the artist would die from a heroin overdose, aged 27. “He began to overproduce and would not listen to advice. There is a crystal-clear vision in his work from the early 1980s that we rarely see in later work, which is more confusing and uneven,” Tsingou says. “Market prices are often confused with artistic achievement, but in Basquiat’s case, they are spot on.”

But finding paintings dating from the early 1980s is difficult. Some of the best examples belong to US collectors such as Eli Broad, Don and Mera Rubell, and Herbert and Lenore Schorr. Auction houses and dealers have repeatedly approached owners of these works, asking to buy them. “Massive guarantees have been offered,” Nahmad says. “I’ve made unprecedented offers to the major collectors for their Basquiats on behalf of clients and they’ve all been rejected. They’re not willing to part with their masterpieces.”

When dealers do secure such paintings, they do not have them for long. Acquavella Galleries had planned to display Basquiat’s Loin (1982) at Frieze Masters but told The Art Newspaper before the fair that the work “is now under consideration for sale so, unfortunately, we will no longer be exhibiting it [on our stand]”.

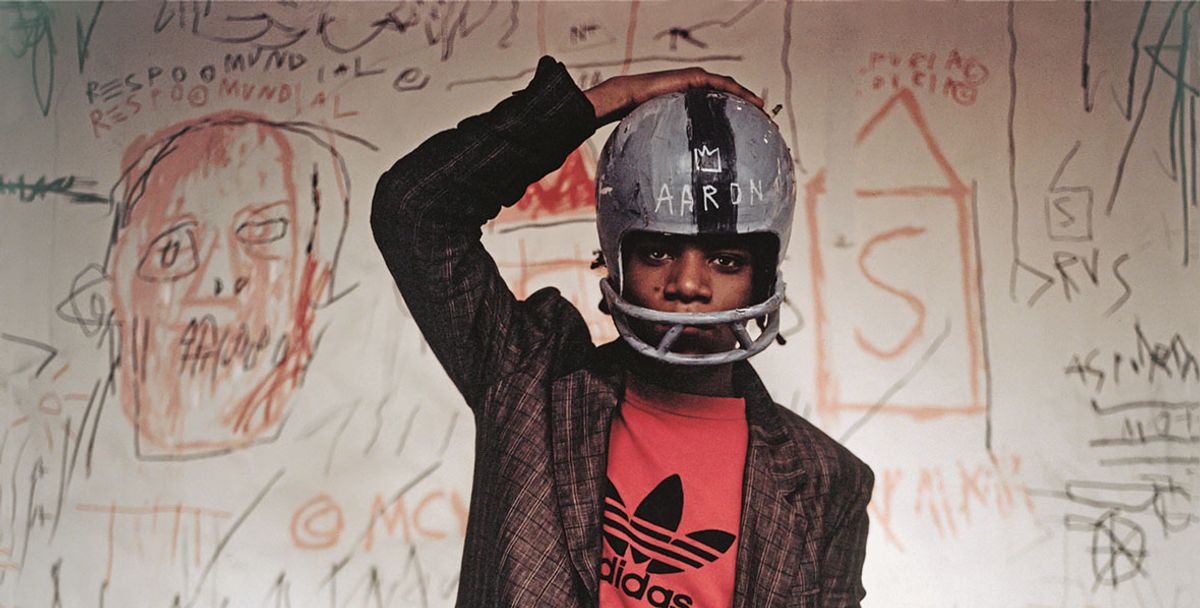

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar

Meanwhile, Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, which owns a collaborative work entitled Cilindrone (1984), made by Basquiat with Andy Warhol and Francesco Clemente, is not willing to part with it. The canvas can be seen on the stand of Thaddaeus Ropac at Frieze Masters, as part of a display inspired by George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, but it is not for sale. Another painting by Basquiat entitled Big Sun (1984) is on offer at the stand of Van Weghe Fine Art for around $4m.

Expanding the market

As the hunt for top works by the artist from the early 1980s continues, expect to see dealers and auction houses exploring later periods and bodies of works. Basquiat “still made extraordinary work after 1982”, says Eleanor Nairne, the co-organiser of the Barbican Art Gallery’s exhibition Basquiat: Boom for Real (until 28 January 2018)—the first large-scale show in the UK of the artist’s work. The exhibition, which includes more than 100 works, aims to put Basquiat in the context of the wider New York cultural scene and focuses on his relationship to music, writing, performance, film and television.

Nairne singles out King Zulu (1986), on loan from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona, as a “phenomenal painting”. The canvas shows jazz musicians floating on a deep-blue background with a black-face mask in the centre of the composition.

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar. Courtesy Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona. Photo: Gasull Fotografia

There are many other examples of strong work from the later 1980s, Nairne adds. “I hope people will begin to appreciate the breadth of his style. The market tends to create a signature style for artists,” she says.

In Basquiat’s case, prized works include paintings with skulls, crowns and anatomical drawings inspired by the textbook Gray’s Anatomy, which the artist’s mother gave him when he was recovering from a car crash. “But Basquiat had no signature style. He was incredibly experimental and reinvented his work every three to six months. There are still aspects of his work that are not fully understood,” Nairne says.

One thing that is now universally appreciated is Basquiat’s importance as an artist. Institutions were slow to understand his work and he is woefully under-represented in museum collections. In his recent monograph, The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat (published by Enrico Navarra Gallery, New York), Fred Hoffman writes that in the year following Basquiat’s death, Herbert and Lenore Schorr offered the Museum of Modern Art in New York the opportunity to choose a painting from their collection as a gift. “The museum replied that having a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat was not even worth the cost of the storage.”