Jenny Holzer’s multifarious occupation of Blenheim Palace, which was unveiled on Wednesday night (27 September) acts as a stunning and unavoidable reminder that Britain’s stateliest of stately homes—a world heritage site and the country’s only non-royal palace—is also a spoil of war. These days the emphasis tends to be on Blenheim’s status as Vanbrugh’s architectural masterpiece, set in spectacular grounds designed by Capability Brown and the birthplace of Winston Churchill, rather than the less edifying fact that the house was given by Queen Anne to the first Duke of Marlborough as a reward for defeating the French at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704.

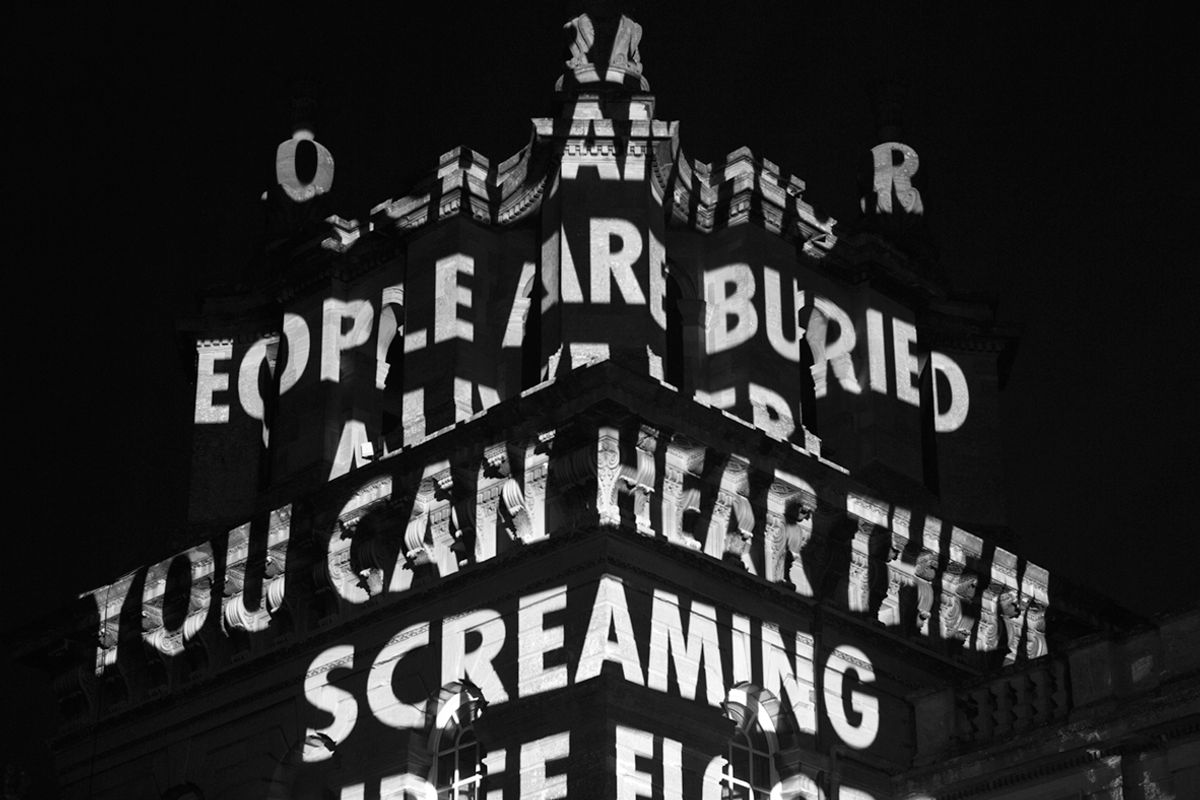

No longer. Now Blenheim’s military origins have been comprehensively rebooted with Holzer effectively transforming every part of the place into a war memorial, devoted to more recent conflicts and their still reverberating consequences. Torrential rain on the opening night only added to the sombre mood as dusk fell and a spectacular tide of light projections drenched Blenheim’s ornate façade. Titled ON WAR these texts covered the house—as well as an island in the lake—with haunting first hand accounts of the war in Iraq given by British war veterans and active military personnel as well as testimonies of those affected by the Syrian civil war.

2017 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Edd Horder

Inside the grand palace interiors there are more gruelling reminders of modern warfare. A giant LED sign dangling in the great hall is incandescent with the interviews of former detainees and defectors from the Syrian military. Holzer’s many “redacted” paintings, concealing and revealing chilling fragments from US military documents, are propped in ceremonial rooms lined with the boastful portraits of the Marlborough dynasty. In a cabinet of precious porcelain, a human shoulder blade is tucked in amongst the teacups. There are more human bones neatly stacked on a large gilt and marble table in Blenheim’s opulent saloon, taking the place formerly occupied by a 19th-century silver table ornament that shows the first Duke writing his victory dispatch from the battlefield of Blenheim.

2017 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Edd Horder

In contrast to these often dramatic interventions, Holzer preferred to keep a low profile on the opening night, wandering almost incognito through the rooms of Blenheim and out by the lake. But when I caught her she did wryly admit her pleasure on discovering how so many of her paintings seemed almost uncannily to co-ordinate with the colours of Blenheim’s opulent interiors. She also declared herself especially happy at being able to drape a coverlet embroidered with an account of a dying soldier on top of the very bed in which Winston Churchill had been born. (Let’s not forget Churchill’s central historical role in how much of the Middle East is still divided up today.)

Edd Horder

Unfortunately the large exterior projections, which Holzer modestly describes as “among the best of the offerings”, are only lighting up the outside of Blenheim until 10 October. But they live on through OF WAR, a specially developed mobile app that overlays specific surfaces in the palace with versions of the projected texts. In an unusually mischievous moment, Holzer has also given the female, marble dragon-monster that lurks beneath the first Duke’s grandiose tomb in the chapel a new digital lease of life—when you walk into the library she flies around the room. Whether or not this refers to the time-honoured Marlborough family tradition of forbidding Duchesses to remain in Blenheim after the demise of their Duke husbands, is not known. But there’s possibly a clue in Holzer’s statement that “she’s supposed to represent envy and we’ve made her huge and let her loose in the library. She’s got six breasts and her tongue matches her tail—just watch her fly!”