As a summer full of marches and demonstrations draws to a close, with no sign that the mood in the US has become any less sour, the Whitney Museum of American Art has staged an ambitious survey of activist art. Through a selection of items from the museum’s permanent collection in a range of styles and media, the show offers a pointed reflection on art and protest over the past eight decades, from anti-war protest signage to abstract painting.

The exhibition is organised through eight thematic sections, each pertaining to a significant political rallying point. Notably, the show's organisers explicitly recognise that the historical narrative is far from closed. "The adjective ‘incomplete’ in the title is a way to suggest that the work of protest is on-going," says David Breslin, one of the curators. "If you look to the archival section of the exhibition that explores the Whitney as a site of protest in the 1960s and early 1970s, you'll see that we're still—as a culture, as a nation, and as an institution—contending with many of the same issues including inclusion, visibility, and accessibility.”

In light of this recognition, a selection of letters from the Whitney’s archive are a particularly self-reflective inclusion. These written appeals to Whitney administrators from figures like Robert Morris, Eldzier Cortor and the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition demand a more inclusive and accessible exhibition programme. The earliest of these artefacts in the show concerns the representation of artistic styles rather than the identity of the artists. A 1960 letter from 22 figurative artists including Edward Hopper and Jacob Lawrence implores the then-director Lloyd Goodrich to increase the number of image-centric works in the museum’s exhibition programme after a 1959 show of contemporary painting included primarily abstract, non-objective works. Goodrich replied in defence of the museum’s curatorial decision, stating that abstraction was at the forefront of American painting.

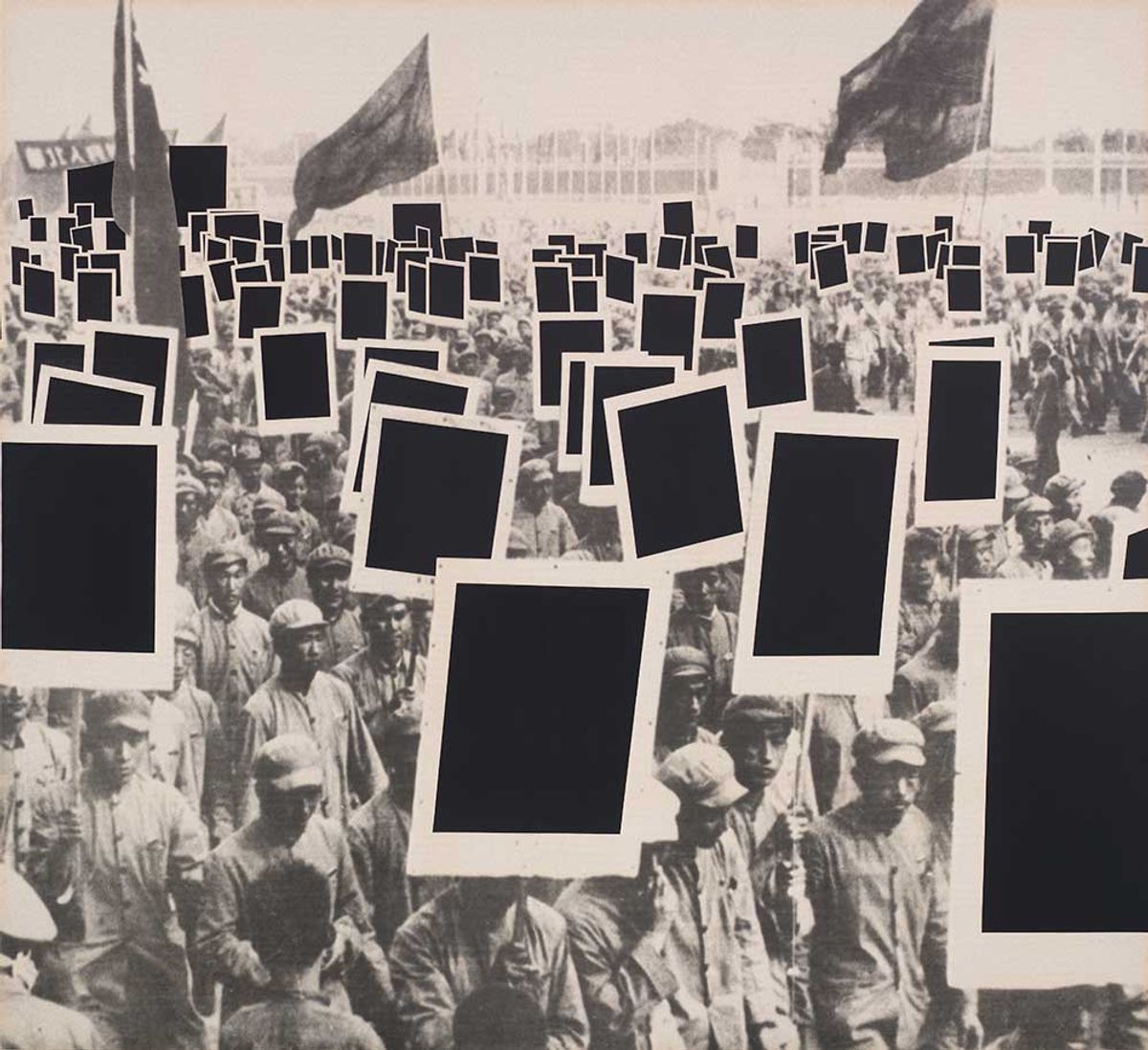

On the other side of this wall, perhaps as an homage to Goodrich’s commitment to the radical possibilities of abstraction, is Abstract Painting (1960-66) by Ad Reinhardt. Accompanying Reinhardt’s monochromatic black canvas is a selection of black-and-white documentary photographs, including a propaganda portrait of the Black Panther Party's co-founder, Huey P. Newton. A caption in the photograph states his famous demand that "racist dog policemen must withdraw immediately from our communities." The combination of Reinhardt's painting with the photograph encourages a connection between the two media and the extent to which they might be politically transformative—Reinhardt rejects the tradition of painterly illusion, while Newton refuses to tolerate state-sanctioned violence in his community. Both projects are incomplete.

Protest against police violence is evident elsewhere in the show. Carl Pope’s installation Some of the Greatest Hits of the New York City Police Department: A Celebration of Meritorious Achievement in Community Service (1994) is a wall of engraved trophies and plaques, each representing an act of police brutality against New York City’s citizens of colour between 1949 and 1994. This representation of racist violence is particularly salient: twenty years after the work was made, sports arenas—especially football fields—have become sites of protest.

AIDS-era activism is thoroughly represented in photography and printed matter. A giant photograph by AA Bronson of his collaborator Felix Partz hours after his death in 1994 prominently faces visitors from a distance. The picture is pixelated and haunting, so that details diminish up-close, as if Partz’s body dissolves upon approach. Nearby, a small framed poster by Félix González-Torres commissioned by the Public Art Fund in 1989 names the murdered gay rights activist Harvey Milk in white print at the bottom of a blank black plane, literally leaving room for imaginative projections.

Some recent acquisitions are on view here for the first time, such as Senga Nengudi’s Internal I (1977), a sculpture of distorted nylon hosiery stretched nearly to its limits, and Julie Mehretu’s Epigraph, Damascus (2016). Mehretu’s imposing composition, spread across six framed panels, contains clean, linear drawings of Damascus architecture covered with sweeping, gestural black marks, suggesting the erasure and destruction of Syria.

Also newly exhibited are selections from the Daniel Wolf collection of protest posters, a diverse portfolio of 1960s and 1970s anti-war propaganda. The collection, which the museum is still archiving, recalls moments that are at once similar to and different from our own. Design technology has changed, as has the way warfare is waged. But US military power remains a consistent destructive force in the world in the decades following Vietnam.

As ambitious and comprehensive as this one-floor exhibition is, its curators remain realistic about its scope: “This exhibition can't tackle every issue,” Breslin says. “It's not only a matter of space; since this is a show organised from our collection, it's also a matter of what the collection holds and what stories it permits us to tell. The collection is deep and complex. But it also isn't complete. There's more work to be done."

In presenting this selection of works, the Whitney recognises a sense of urgency in the present moment and offers a space for reflection on the past—an admirable move on the part of a powerful cultural institution. Meanwhile, art continues to work through its relationship with politics, an exploration that remains incomplete.

Jamie Keesling is a writer and Art History faculty member at the School of Visual Arts.

An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, on-going