Few cities have been more fiercely fought over than Jerusalem. In its more than 5,000-year history, during which it has become a sacred site for Jews, Christians and Muslims, it has been attacked 52 times, captured 44 times and destroyed twice. Even today, “there is no apolitical way of exhibiting the history or the current realities in Jerusalem”, says Ilan Pappé, a professor of history and the director of the European Centre for Palestine Studies at the University of Exeter—especially considering that 2017 is the 50th anniversary of its most recent takeover, when Israel captured East Jerusalem during the Six Day War.

This autumn, both the Israel Museum and the Palestinian Museum have shows about the city. At the Israel Museum, an exhibition tentatively titled Jerusalem in Detail is based on research by the Israeli architect David Kroyanker. It looks at how different cultures have left their marks on the city’s buildings over time, primarily through photographs. It also explores the meanings behind the monograms that displaced Arab families have in their homes, says the curator, Dan Handel. “We attempt to stress the links between ideas that emerge in different cultural and religious contexts,” he says.

Assaf Evron

Meanwhile, the Palestinian Museum’s exhibition Jerusalem Lives is the first in its new building, which opened in May 2016. The main part of the show includes contemporary works of art and 20 large-scale commissions in the museum’s gardens by international artists including Oscar Murillo and Palestinian artists such as Mona Hatoum, Emily Jacir and Khaled Jarrar.

“I didn’t [focus on the Six Day War] in a very literal sense because I don’t want the culture of Palestinians or people living in Palestine to be defined by catastrophe,” says Reem Fadda, the curator of the exhibition and the former associate curator of Middle Eastern art at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Instead, the overtly political and participatory show “aims to focus on the living aspect of the city and support its people”.

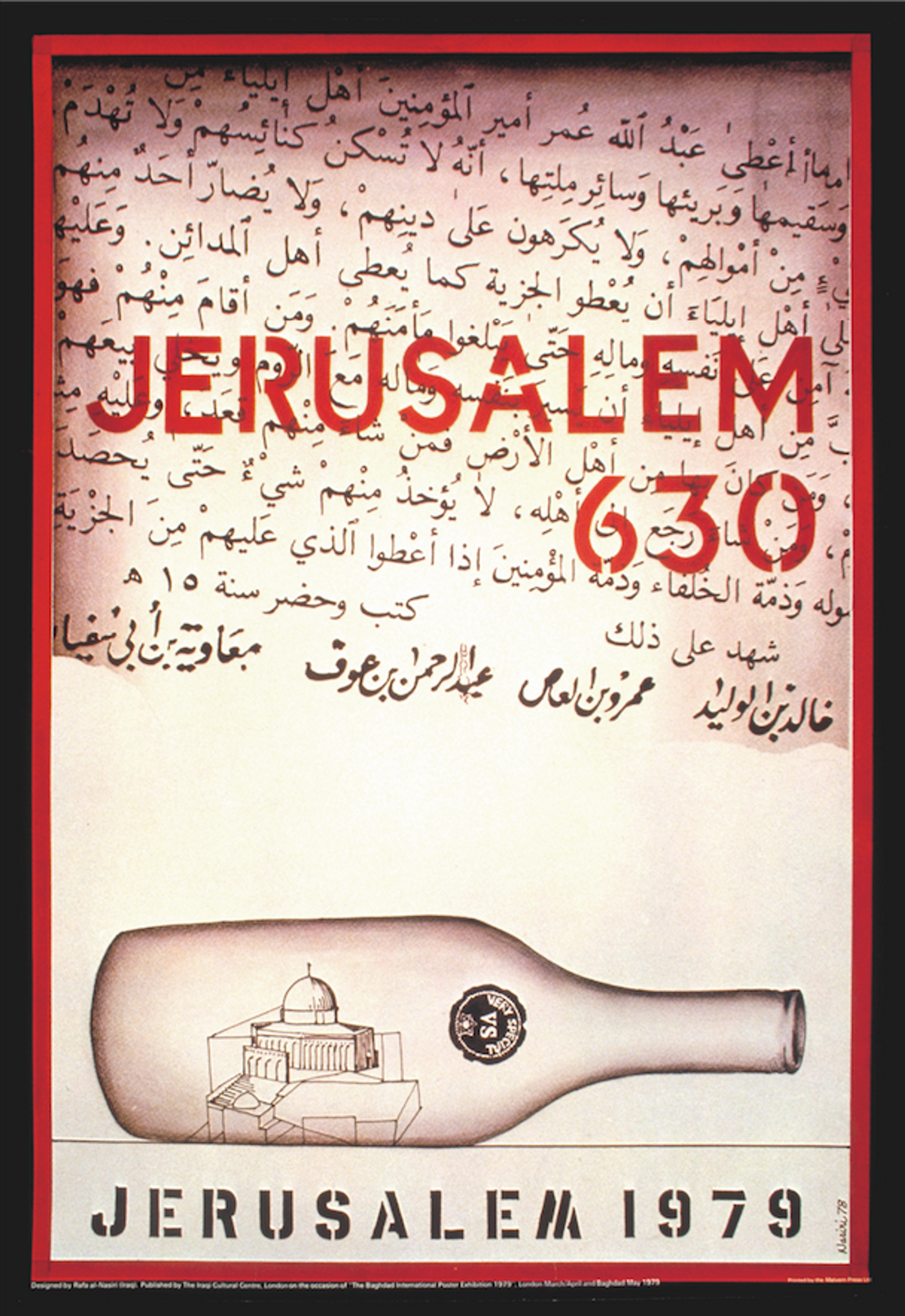

The Palestine Poster Project

The main conceptual difference between the shows is the way in which they address globalisation and multiculturalism. While the Palestinian Museum focuses on contemporary art and frames Jerusalem and its ongoing conflict as an example of the failures of globalisation, the Israel Museum’s show is more historical and discusses multiculturalism positively as a contributor to the aesthetics of the city.

The difference speaks to a wider political rift. “It is difficult to discuss Jerusalem, particularly with regard to the Old City, where contestation of space and historical memory is not just a subject for historians, but continues on to this day,” says Michael Stephens, a research fellow for Middle East studies at the Royal United Services Institute, a London-based think tank for defence and security studies.

But is there space for meaningful dialogue? “One day there will be—and maybe it has already begun—a process we call in historiography ‘the bridging narrative’: a more inclusive way of looking at the possible heritages, chapters of history and artistic representations,” Pappé says. “But it may be too premature.”

• Jerusalem in Detail, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 3 October-May 2018

• Jerusalem Lives, Palestinian Museum, Birzeit, until 15 December