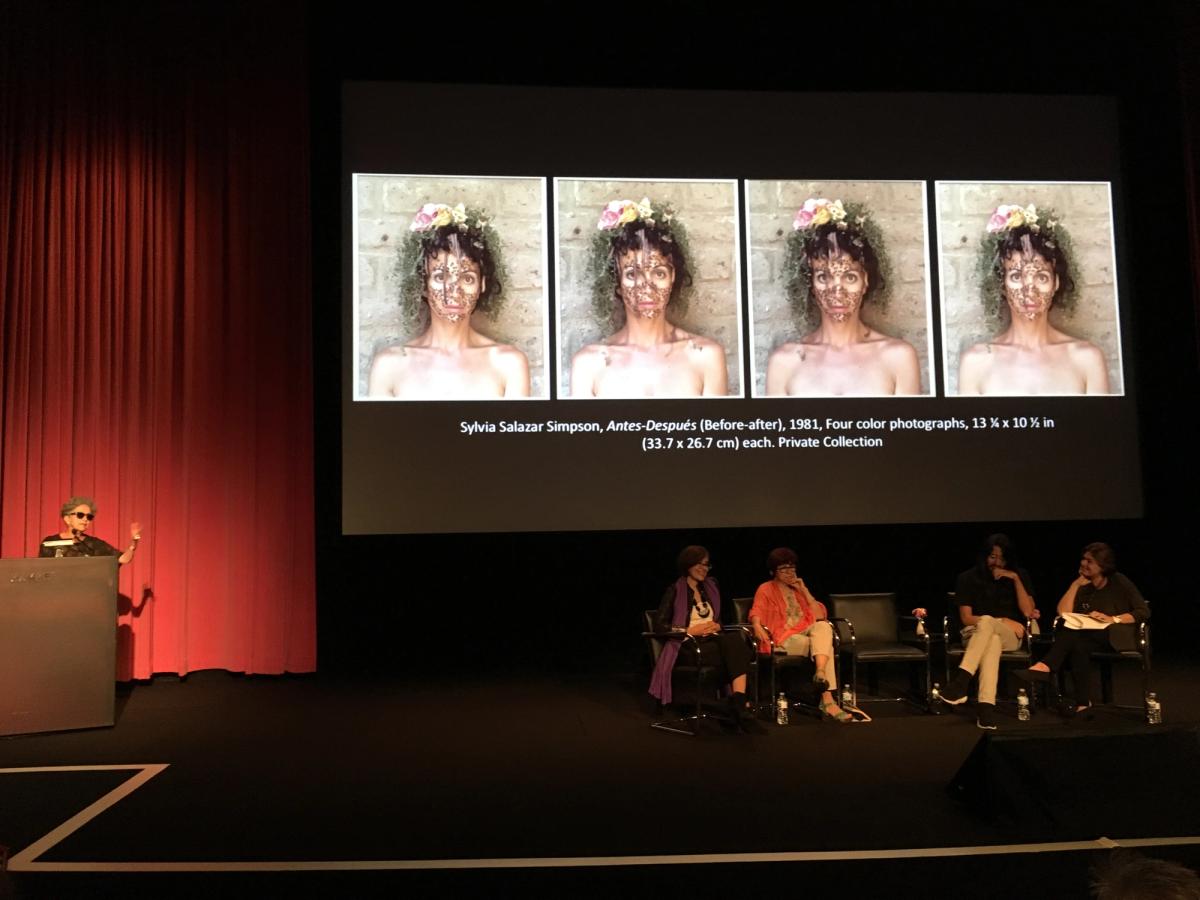

Nobody ever said it would be easy to organise a show of women artists from over a dozen countries across Latin America. That was one of the points made during Monday’s symposium for Radical Women: Latin American art, 1960-85 at the Hammer Museum, easily the most anticipated exhibition of Pacific Standard Time LA/LA and arguably the one with the largest reach, as it is now set to travel to the Brooklyn Museum and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo.

While the big opening party took place on Saturday night, complete with cookies that spelled out the letters “Arte”, reprising a 1976 work in the exhibition by the Brazilian artist Regina Silveira, the symposium felt festive, too—up to a point.

Gerson Zanini

The exhibition’s curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta, who led two of the day’s bilingual artist-packed panels (the Hammer chief curator Connie Butler led the third), acknowledged challenges in realising the ambitious show, which originally set out to cover a period nearly twice as long.

Fajardo-Hill also acknowledged hitting roadblocks early on from people who “considered something which is quite absurd: They considered that we were already in the era of the queer, so women [are] not relevant as a subject."

She also found some artists were resistant to the idea of the group survey. “Some said no for very sad reasons, like I don’t want to be bunched up with women, also for fear of being stereotyped and also for this sense, you know, they are already too famous,” she said. “I won’t say the names but it did happen.”

Thank you for letting me visit your country even though I am a bad hombre and a nasty woman, and I’m not going to pay for the wallMónica Mayer

Other key issues that emerged over the course of the day included how to preserve or communicate “radicality” in a museum setting; the importance of recognising indigenous artists (one buzzword: “decolonisation”); and the lack of developed feminist traditions in several Latin American countries, where artists often joined left-wing, anti-dictatorial groups to agitate for basic human rights and working conditions while also pressing the agenda on gender issues (another buzzword: “double militancy”).

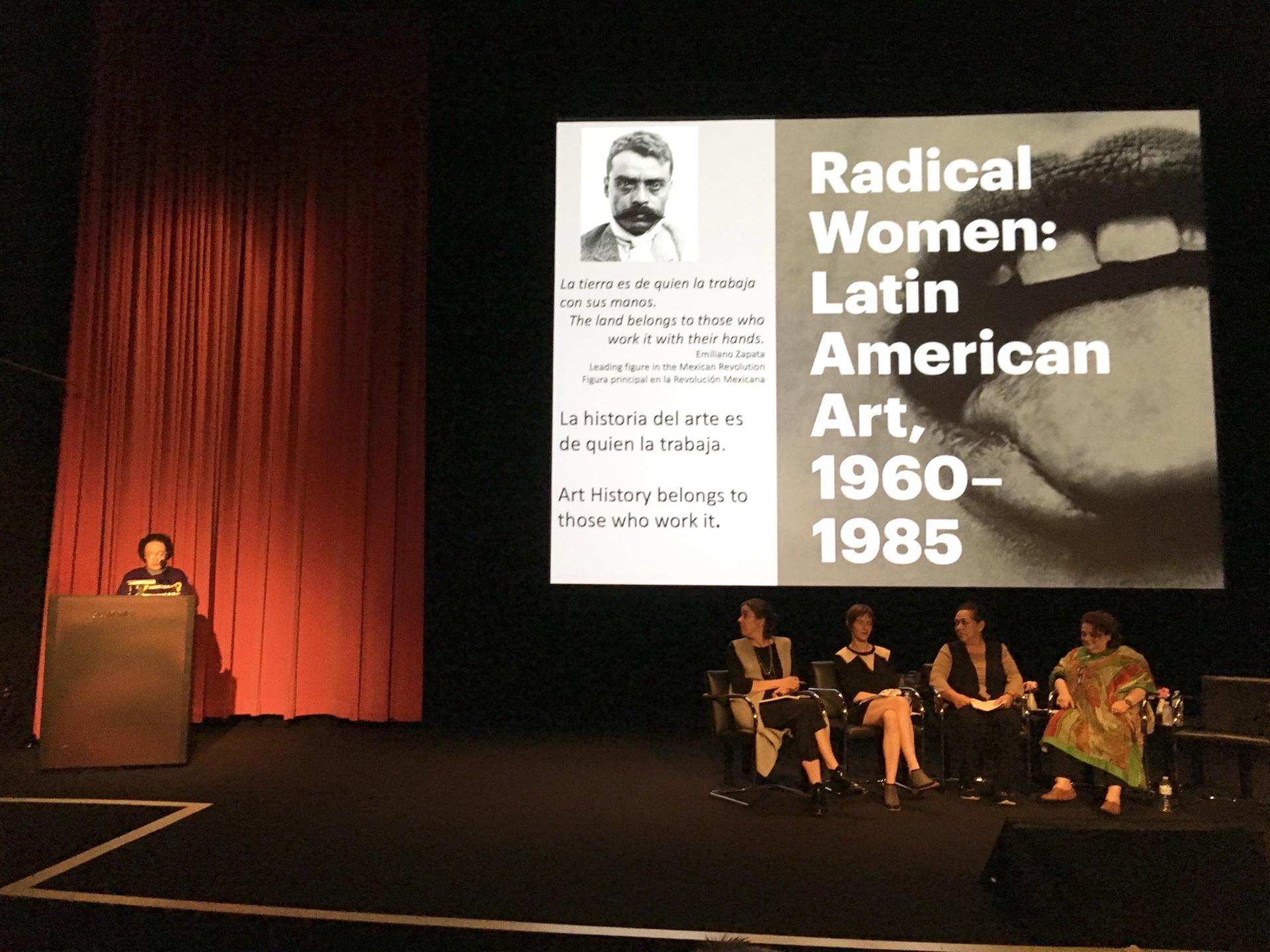

The last issue was addressed most dramatically by Mónica Mayer, the Mexican artist-activist who participated in the hotbed of feminism known as the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles during the late 1970s and started her talk with a thank-you “for letting me visit your country even though I am a bad hombre and a nasty woman, and I’m not going to pay for the wall”.

Jori Finkel

“Is there a history of feminist art in Latin America?” she asked. “Actually there are many histories. Each country has its own. But the answer is not that simple and entails problems of translation, visibility and legitimacy. The histories exist. Are they strong and have we known about each other in our different countries? No, not necessarily.”

Her recurring theme: “The work of a feminist artist is never done: you have to do the artwork and document it.”