I spent weeks this summer reading exhibition catalogues and talking to curators about their upcoming shows to try to get a toehold on the vast Getty-organised enterprise known as Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, which at its core consists of 75 museum exhibitions on Latin American and Latino art. But even, so there were serious surprises for me just about every step of the way in the sprint-marathon of opening week. Here are the pieces that most effectively slowed me down or gave me a reason to linger in the frenzy of museum exhibitions—the things I most want to see again.

Private collection, courtesy of Galeria Jaqueline Martins

Videos by the late Brazilian artist Letícia Parente in Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-85 at the Hammer Museum. In the middle of this wonderfully unruly exhibition is a short 1982 video by Parente called Tarefa 1 (Chore 1), in which a clothed woman, presumably the artist, crawls onto an ironing board and lays face down while she is pressed head to toe with the iron. It’s not clear whether the iron is hot. Nearby is her 1975 video in which she uses needle and thread to sew the words “Made in Brasil” onto the sole of her foot. Her hand and foot are both remarkably steady. In such works Parente re-enacts, with a sly sense of humor, the routine violence committed against women by men and their military and maybe even corporate instruments. In effect, she fiercely controls the narrative of being controlled. Contemporaries like Chris Burden and Vito Acconci, who also turned their society’s machismo against themselves, seem a touch soft by comparison.

Collection of John Jerit © The Estate of Martín Ramírez / Courtesy Ricco/Maresca Gallery

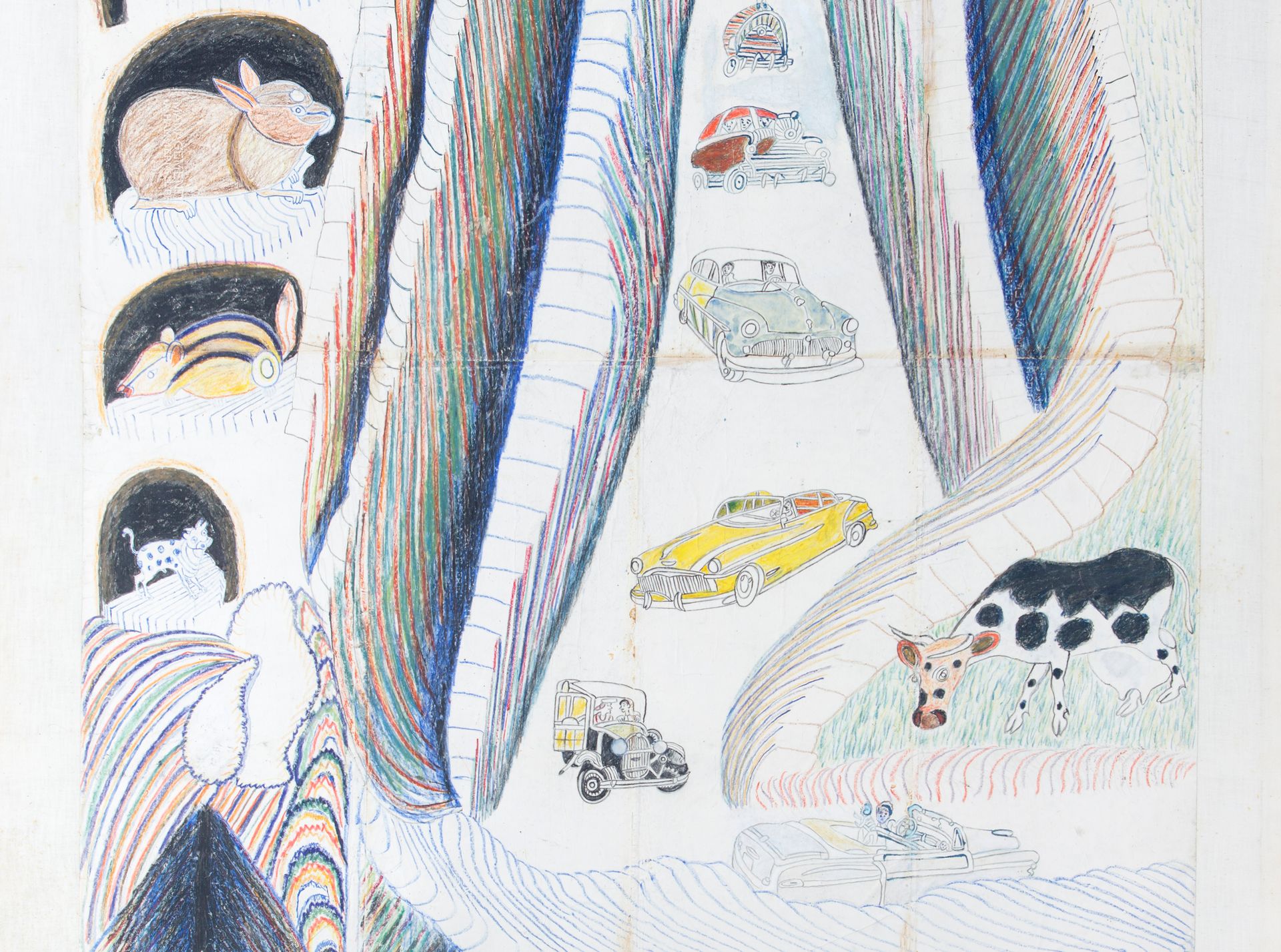

The large drawings by the Mexican-born artist Martín Ramírez at the newly opened Institute of Contemporary, Art Los Angeles. Epic versus lyric is an old Aristotelian distinction used with poets, but it can just as easily be used with visual artists: those who go for sweeping historical narratives versus those who go for more personal, intimate or even introverted moments. I had always pegged Ramirez for an unflagging lyricist, with his repetitive patterning of tunnels and arches made mainly during the 1950s when he was institutionalised at the DeWitt State Hospital. And those works are prominent in the current survey at the ICA LA, but so are a few larger pieces rarely seen on the West Coast, including a nearly 12-foot-high work on paper that establishes a full cast of characters (animals off road and vehicles on it), a shifting landscape and a long, eventful journey.

Jori Finkel

Jose Dávila’s sculpture-puzzle Sense of Place (2017-18), now at West Hollywood Park, produced by LAND (Los Angeles Nomadic Division). Remember when Gabriel Orozco rolled that ball of plasticine through the streets of New York to see what it would pick up? Dávila’s new sculptural project takes a similar premise of art as urban explorer. Right now, his sculpture looks like an eight-foot-tall white minimalist cube, but the structure was carefully designed to be dismantled and spread throughout the city at key stages over the next year. Expect the fragments, soon to be individual sculptures in their own right, to acquire their own history, patina and maybe even graffiti through their presence in a particular community. “I like to think of it as a living sculpture,” said LAND’s curator Shamim Momin. “It’s a fractal of Los Angeles,” added the artist.

Jori Finkel

Judy Miranda’s Mother (1983), in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano LA at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Pacific Design Center branch. Even in an emotional section of the show devoted to Aids, this work stands out for its unsentimental tenderness. It consists of six photographs arranged on the wall in the form of a cross. Each picture shows a detail of the same man (armpit, nipple, penis), identified in the wall label as a friend of the artist who, dying of Aids complications, asked her to create a portrait of him for his partner. Something about using fragments of the body as a posthumous love letter got to me. The last time this work was shown was at the subject’s funeral, said the show’s co-curator David Evans Frantz.

Jori Finkel

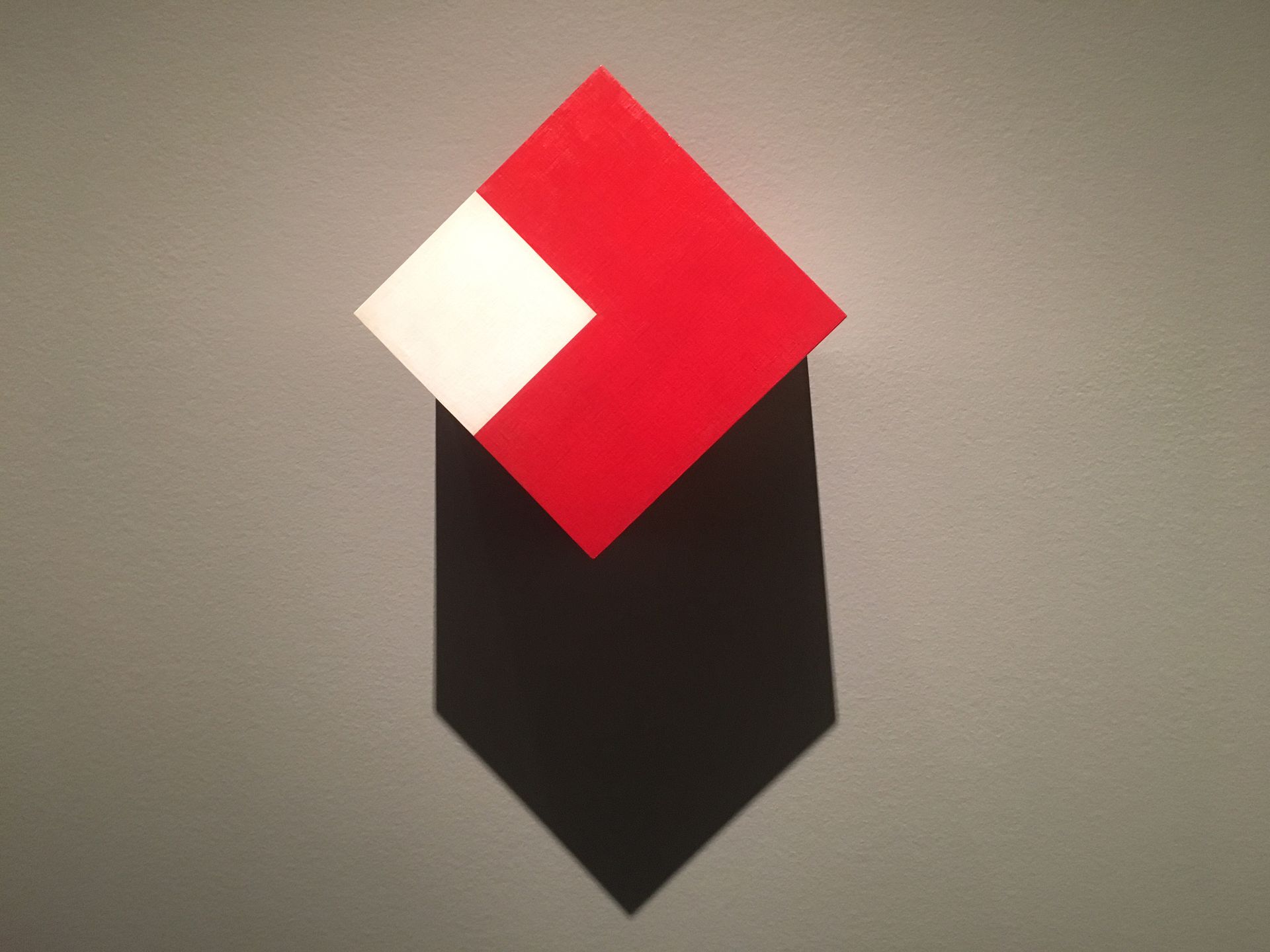

Willys de Castro’s Active Object (Red/White Cube) (1962) and other re-orientations in Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisnersos at the Getty Museum. A collaboration between Getty conservation scientists and art historians, this show is filled with abstract geometric painting and sculpture so pristine that every shadow counts. De Castro’s Active Object, an oil-on-canvas-on-plywood illusion of a white cube within a red cube, casts a great one, but that wasn’t always the case. This is one of three artworks in the show where conservators found documentation that changed the orientation used for hanging the work. The de Castro discovery was made just in time to feature the work in its new orientation on the exhibition catalogue cover.

Courtesy of the photographer and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center © Raul Ruiz

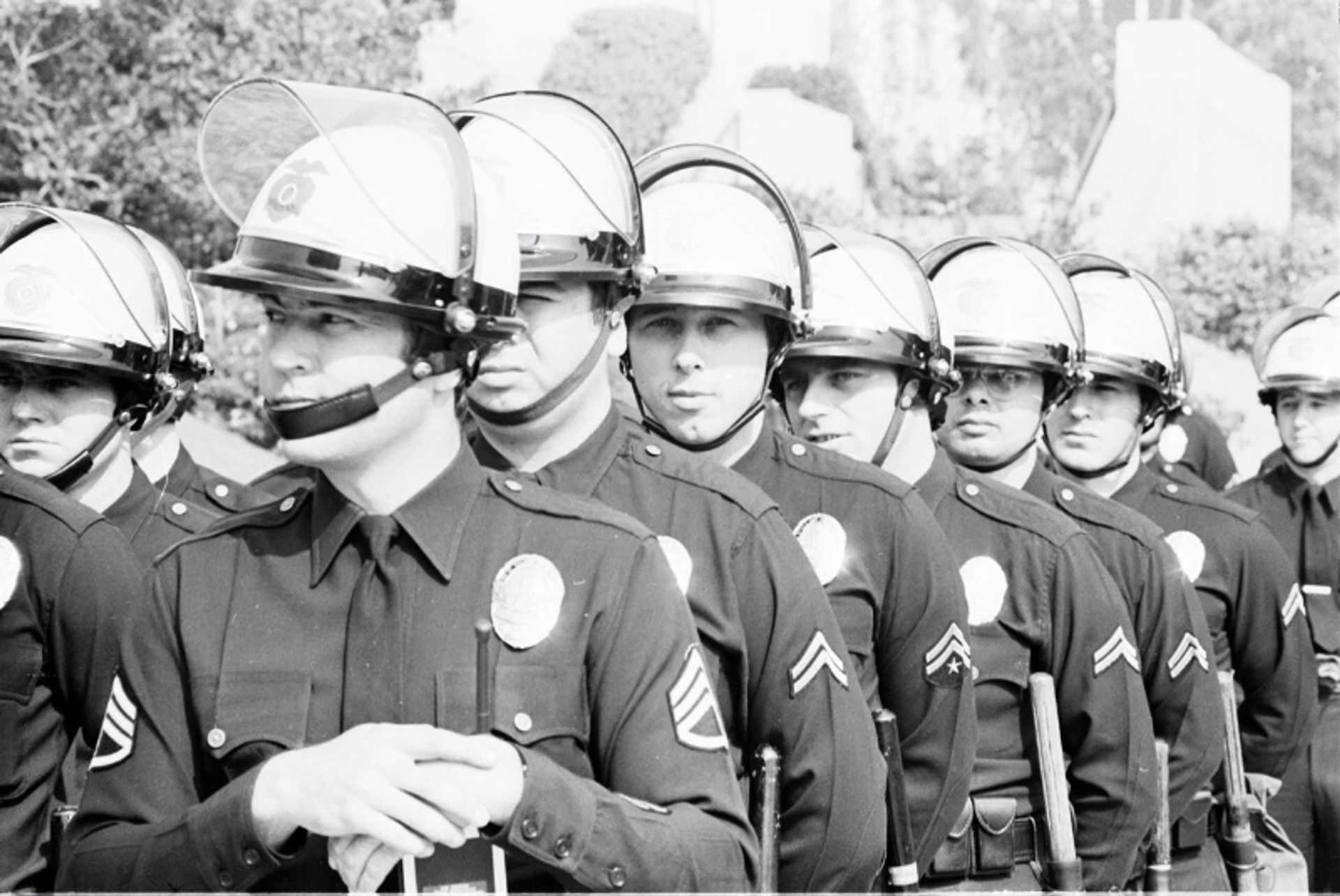

Images of the LAPD—and police brutality—from the 1960s and 70s in La Raza at the Autry Museum of the American West. Even though most PST exhibitions were at least three years in the making, many curators noted that their shows feel especially timely now, in light of White House policies targeting and endangering immigrants. This survey of photographs from the massive archives of the Chicano newspaper-turned-magazine La Raza (1967-77) feels like the most urgent or relevant of them all. Faced with a trove of nearly 25,000 images, the curators did a remarkable job of storytelling and theme-seeking, whether bringing together shots of handmade protest signs or images of police brutality (an attempt to watch the watchers), culminating in a blown-up contact sheet documenting the conditions of the 1970 murder of Ruben Salazar. The Los Angeles Times journalist was killed by a sheriff’s wall-shredding tear-gas projectile while sitting in the Silver Dollar bar in East Los Angeles, where he was taking a break from covering the National Chicano Moratorium rally against the Vietnam War—an innocent activist bystander.