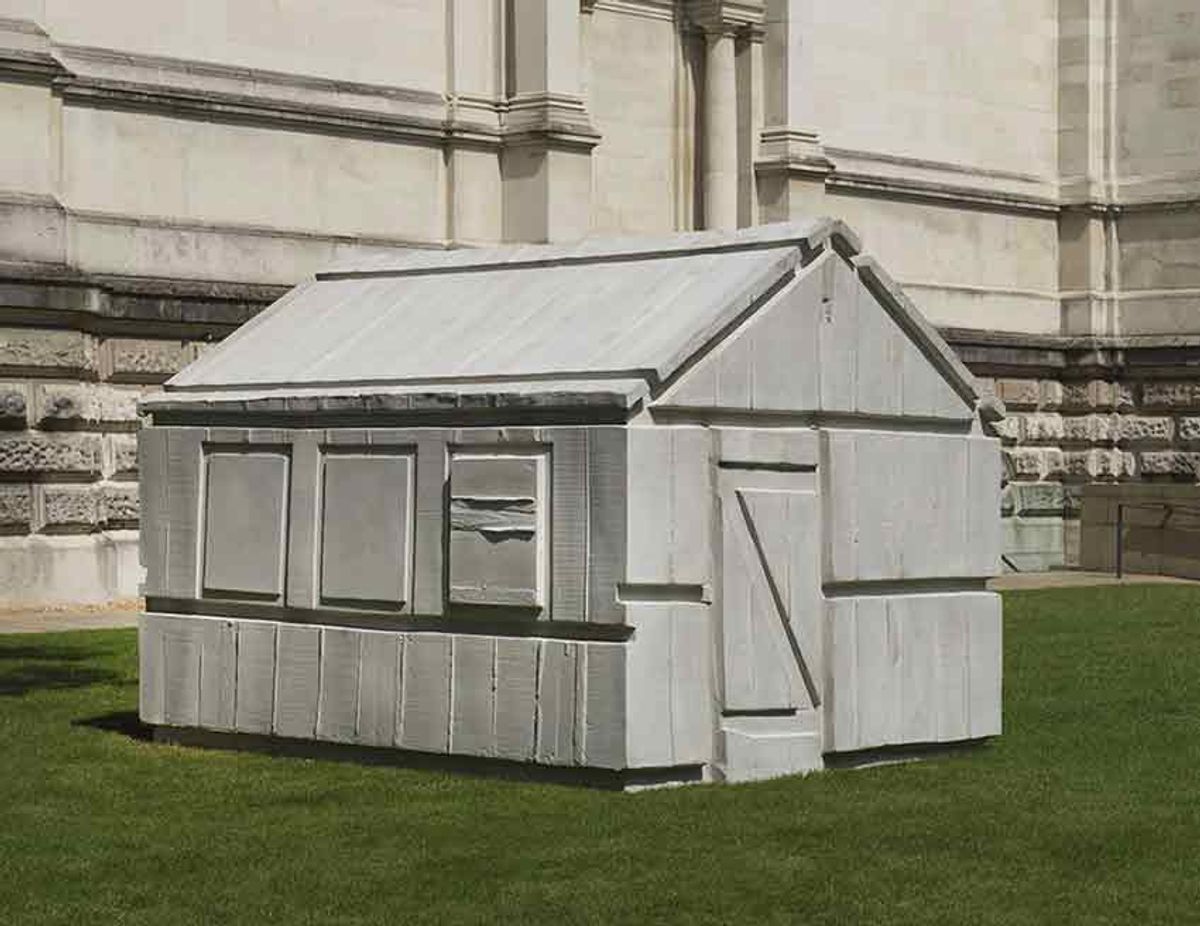

On very special occasions, Tate Britain’s 1979 extension is opened up into a vast, single, top-lit space. This is the case for Rachel Whiteread’s career survey (until 21 January 2018) of 30 years of work, from breakthrough sculptures made the year after she graduated from art school, to pieces fresh from the studio. Whiteread’s work has been remarkably consistent. For Closet (1988), she cast the interior of a humdrum wardrobe in plaster and covered it in black felt. Ever since, she has been “mummifying the air”, as she once put it. The point of the Tate exhibition, according to its curator, Ann Gallagher, is to show that “through consistency of process, there’s an incredible variation”.

Were it not for permafrost, we would know next to nothing about the Scythians. Originating in the 10th century BC in central Asia and Siberia, the Scythians spread to inhabit an area stretching from the Black Sea to the northern border of today’s China, and disappeared from history in the third century BC. But, having no written language, they left no records. All evidence about them comes from other (biased) sources, such as Herodotus and Achaemenid (Persian) writers. Their elaborate burial rituals involved the interment of many and various objects from which the exhibition Scythians: Warriors of Ancient Siberia (until 14 January 2018) at the British Museum weaves a story of their way of life.

“It’s splendid. I’m obsessed with it.” So wrote Matisse in a letter to the French poet Louis Aragon. The subject of his admiration was a Venetian chair that he had found in an antique shop. The chair along with the charming coloured pencil drawings of it, form part of Matisse in the Studio (until 12 November) at the Royal Academy of Arts. This small exhibition revolves around 35 objects—almost all from the French artist’s studio—shown alongside 65 works that depict or were inspired by them. The items range from a pewter jug and glass vase to a Roman torso and African masks. Influenced by the latter, one of the most striking works in the show is The Italian Woman (1916). This is the first of 50 paintings Matisse made in less than a year of a woman called Laurette, who had visited his studio looking for work in the winter of 1916.