Will the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, which will open on 22 September in Cape Town, South Africa, set a new benchmark for private museums? Billed as Africa’s first major contemporary art museum, Zeitz Mocaa is entirely privately funded, but the level of its ambition in every aspect of its operations—from collection building and programming to fundraising and governance—sets it apart from the scores of private institutions that have opened around the world in recent years.

Whether the vast Thomas Heatherwick-designed museum lives up to its initial promise remains to be seen. Paradoxically, its future success lies in establishing its reputation independently of its namesake, the German collector and former Puma chief executive Jochen Zeitz. Many private museums fail to achieve much beyond reflecting the individual tastes of their founders. Zeitz Mocaa aims to do much more than that. If it succeeds it will radically alter the landscape of contemporary art in Africa and put African artists firmly on the international map.

Mission

“For a very long time, the narrative of Africa has been defined by people from elsewhere,” says Mark Coetzee, Zeitz Mocaa’s executive director and chief curator. “This is our attempt at reclaiming that narrative.” The museum focuses on work by artists from Africa and its diaspora, with programming strands devoted to the moving image, costume, performance art and digital platforms.

Building

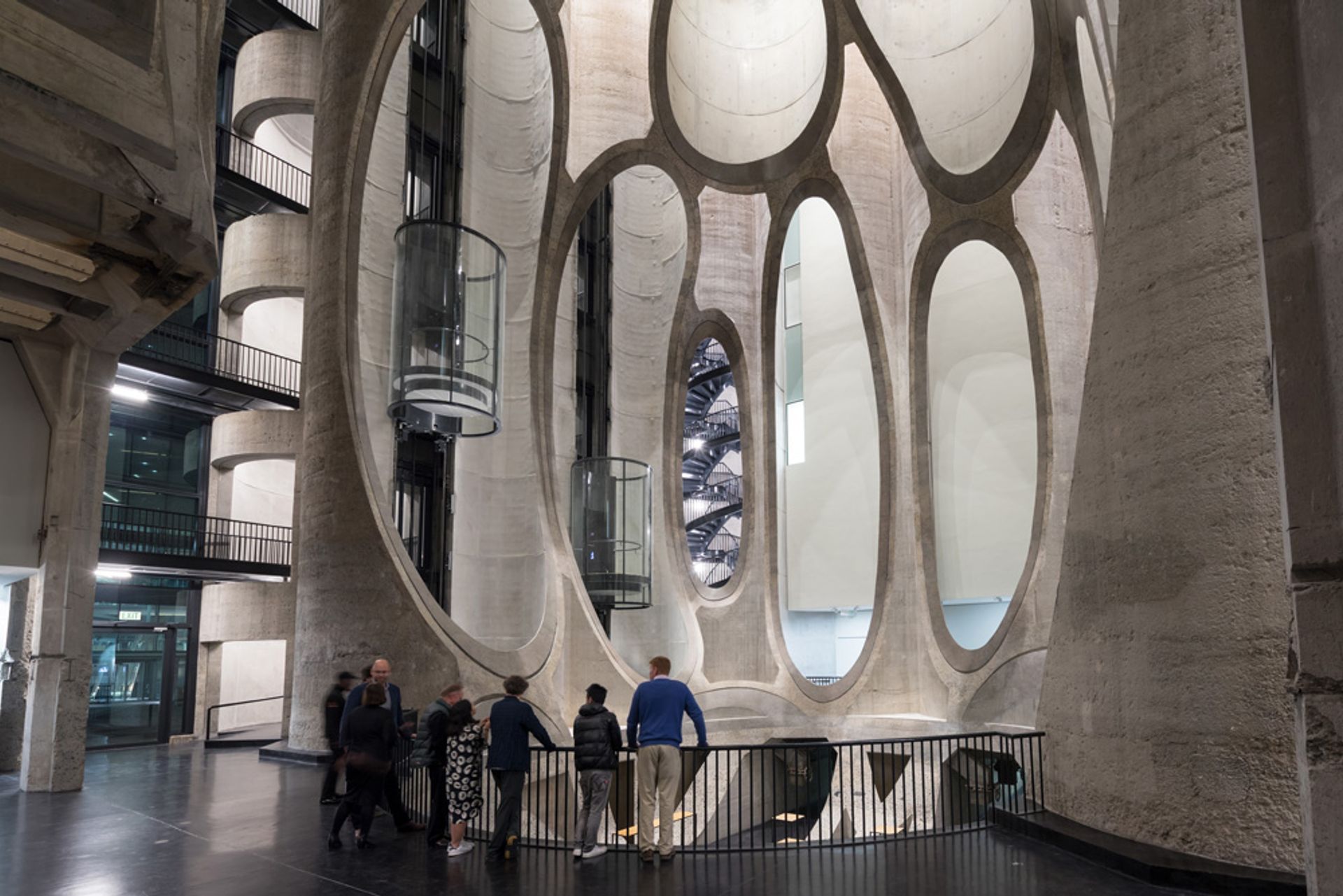

The museum is a collaboration between Jochen Zeitz and the V&A Waterfront, the commercial company which has developed more than 300 acres of waterside property in Cape Town. Its nine-storey 102,000 sq. ft building, a disused granary, was converted by the UK architect Thomas Heatherwick. The V&A Waterfront owns the building and has paid for its ZAR500m ($38.7m) transformation, giving it to Zeitz Mocaa on a 99-year renewable lease.

For his first museum project, Heatherwick has carved a spectacular atrium in the shape of a kernel of corn out of the vertical silos once used to store grain. He has exposed the original, weathered concrete and incorporated the building’s industrial quirks into his design. Around 80 traditional white cube galleries are positioned around the central atrium.

Iwan Baan

Collection

Jochen Zeitz has granted the museum the use of his growing African art collection—assembled with the advice of Mark Coetzee—for his lifetime. “I hope my children will be interested in continuing the collaboration but it would not be fair to impose this on them,” Zeitz says. The museum is also building its own permanent collection through purchases and gifts. Spread over two floors are displays from both collections, including works by the Ghanaian artists El Anatsui and Jeremiah Quarshie; the South Africans William Kentridge, Nicholas Hlobo and Zanele Muholi; the Congolese painter Chéri Samba; UK artists Chris Ofili and Isaac Julien; and Glenn Ligon, Kehinde Wiley and Hank Willis Thomas from the US, among many others.

Courtesy of the artist

Exhibitions

The inaugural temporary shows are dedicated to three African artists. The Angolan photographer Edson Chagas won the Golden Lion for best national pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale with his stacks of posters depicting the country’s capital, Luanda. Coetzee acquired the entire show, which is now restaged in the museum’s basement tunnels (until 13 January 2018). On the third floor, photographs and posters by the Zimbabwean artist Kudzanai Chiurai question the heroic posturing of African male leaders (until 31 March 2018). On the fourth floor, sculptures of the female body, fashioned from cowhide by the Swaziland-born, South Africa-based Nandipha Mntambo, completes the trio (until 27 January 2018).

Courtesy of the artist

Staff

The museum has three full-time curators and plans to hire eight more. Also on staff are three adjunct curators, 11 assistant curators and 11 trainee curators on temporary placements (with funding in place for another 14). The hope is that these trainees will spend a year or two at the Zeitz and then “run other spaces in Africa”, Coetzee says. Zeitz Mocaa has also hired four high-profile curators at large, including RoseLee Goldberg, the South African founder of New York’s Performa biennial, as curator of performative practice and Raphael Chikukwa, chief curator at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, for painting and sculpture.

The museum’s large curatorial staff is unique among galleries set up by private collectors. The Broad in Los Angeles has three full-time curators (the director Joanne Heyler, an associate curator and an assistant curator), while François Pinault’s Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice have just one (chief curator Caroline Bourgeois).

Funding

The museum’s major sponsors include Bloomberg; BMW, which is paying for the commissioning and display of installations in the atrium for the next three years; and Standard Bank, Africa’s biggest bank, which is underwriting free entry to the museum on Wednesday mornings and on South African public holidays. Among its many individual patrons, the South African psychologist and artist Wendy Fisher, who also serves as president of the board of New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, has provided ongoing funding for 13 trainee curators.

Iwan Baan

The museum will also generate its own income through ticket sales (full adult price ZAR180; $14) and revenue from the bookshop, cafe and restaurant. David Green, the chief executive of the V&A Waterfront, is optimistic about the visitor numbers Zeitz Mocaa will attract. The waterfront’s restaurants, shops and tourist attractions draw 24 million visitors a year and Green expects more than one million to come to the museum (of which around half will pay for admission; under-18s enter free).

Jochen Zeitz and the V&A Waterfront have agreed to cover any shortfall for at least a decade. Meanwhile, the museum is raising funds towards a target endowment of ZAR600m ($46m), which Coetzee hopes to reach within five years. This will eventually support 75% of its operating costs, he says. The revenue from a luxury hotel on top of the museum goes to the V&A Waterfront.

Governance

The museum’s board of trustees and advisors, which meets four times a year, includes the UK artist Isaac Julien; the Kenyan-born, New York-based artist Wangechi Mutu and the anti-apartheid activist and retired judge Albie Sachs, among others. The co-chairs are Jochen Zeitz and David Green of the V&A Waterfront.

Governance is key not least because the museum’s director, Mark Coetzee, is involved in acquisitions for its permanent holdings (all purchases and donations are reviewed by an acquisitions committee) as well as for Jochen Zeitz’s personal collection. Critics have pointed to a potential conflict of interest in Coetzee’s dual role and questioned whether museum curators will come under undue pressure to exhibit works belonging to Zeitz.

Coetzee is pragmatic about the arrangement. “Government-funded museums in South Africa are struggling. They have no budget for acquisitions and no money for routine maintenance; they are failing to fulfil their primary role which is the preservation of work for future generations,” he says, noting that the Johannesburg Art Gallery temporarily closed earlier this year after falling into disrepair. “We had to find a new model to make this museum possible on this continent,” Coetzee says. Zeitz’s collection is a “great asset” that museum curators are not obliged to display, he adds. “This independence is enshrined in the contract Zeitz has signed with the V&A Waterfront.”