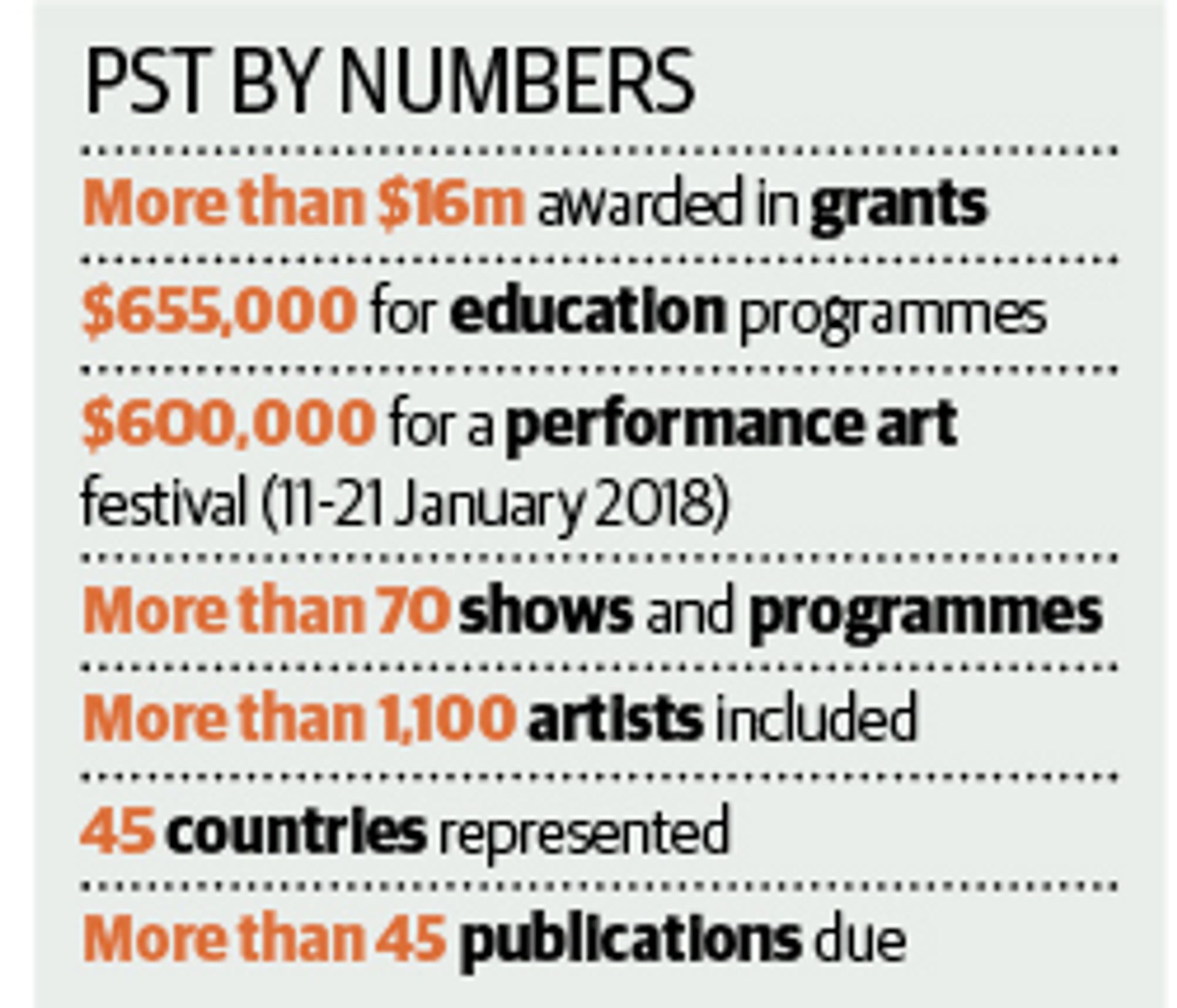

The 2011 inaugural edition of Pacific Standard Time (PST)—the sprawling, J. Paul Getty Trust-backed series of exhibitions and programmes across Los Angeles cultural institutions—was an enormous undertaking ten years in the making. It included 68 museum shows, an extensive oral history project, the publication of more than 40 books and an effort to archive photographs, papers and videos at the Getty Research Institute.

The size of the project did not deter organisers from trying it again. “Even before Pacific Standard Time closed in 2012, there was enthusiasm for doing another one,” says Joan Weinstein, the deputy director of the Getty Foundation.

By many measures, the second edition, which officially opens in September, is even larger. The Getty has awarded more than $16m in grants to various institutions, whereas for the 2011 programme, it handed out around $11m. Last time, there were 60 partner institutions; now there are nearly 80.

The geographic scope is also larger. While the first edition looked to the history of art in Los Angeles from 1945 to 1980, the current one, titled LA/LA, looks beyond the city and into Latin America, with a focus on cross-regional dialogues.

How is such a large event managed and funded? The Getty awards PST grants in two phases: first for research and later to implement programming and publish catalogues. “We learned from the first Pacific Standard Time that the research would change how people thought about their exhibitions,” Weinstein says.

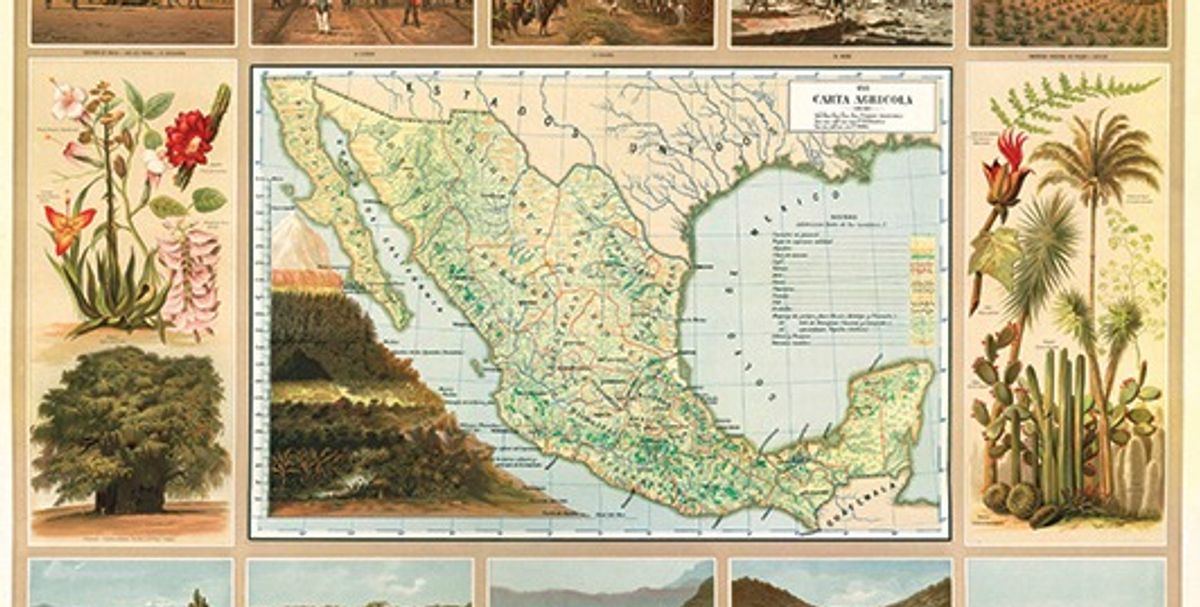

Catherine Hess, the chief curator of European art at the Huntington and a co-organiser of Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin (16 September-8 January 2018), says an initial grant of $200,000 was used to get a lay of the scholarly land. “We brought together a team of advanced scholars to do presentations and look at Huntington materials to see what we were missing from our perspective,” she says.

The money was also used to organise an advisory committee and fund travel. “The travel was hugely important because we needed not only to identify where the best material was but also to begin the process of negotiating loans,” Hess says.

Not every project has such a clear distinction between research and implementation. A Universal History of Infamy (20 August-18 February 2018), an exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) and the 18th Street Arts Center, will primarily present newly commissioned work, which blurs the lines.

“For us, implementation was happening immediately,” says Anuradha Vikram, the artistic director at 18th Street. “We got comments from people that we were a test case for PST as a whole because we were doing things as others were thinking about what to do.”

For the show, 16 artists from around the world took up residencies of various lengths at 18th Street. A total grant of $160,000, supplemented by an additional grant to Lacma (where much of the work will be shown), was used in part to hire a research assistant to help artists organise trips around Los Angeles and gain access to various sites.

The Getty’s role, after awarding grants, is to oversee and promote the events. “PST is somewhat decentralised, but the Getty is at the centre of it,” Weinstein says. “Most of the knowledge about the various exhibitions is here.”

So has this second, larger edition garnered the same enthusiasm for yet another PST? Asked at a press conference in New York in April, James Cuno, the head of the J. Paul Getty Trust said: “Yes, we’re already thinking about it.”