Dreamers Awake, White Cube (until 17 September)

Surrealism was a movement dominated by men and obsessed with women—especially their bodies, which the likes of Magritte, Ernst, Bellmer, Dali et al presented as a vessel for every conceivable male fantasy. But despite the female form suffering all manner of abuse at the hands of the surrealists, from the 1930s onwards many female artists were also associated with the movement, attracted by Surrealism’s liberation of the subconscious, its emphasis on the subjective imagination and its refusal to conform to convention—even if this meant they were relegated to muse status along the way.

A good number of these early female surrealists are represented in White Cube’s terrific survey, which also traces the continuing impact of Surrealism on the work of more than 50 female artists up to the present day. The subjective, the fantastical and the visceral are expressed in paintings, sculpture, prints and photographs as well as film and video—from the painted dreamlike scenarios of Leonor Fini to the sculptures of Kiki Smith and the punkish collages of Linder.

Bodily concerns are frequently explored but from the point of view of the owner, rather than the observer. As early as 1942 British Surrealist Ithell Colquhoun was painting a strikingly suggestive wooden knothole (complete with mossy pubic tuft) and this reclaiming of the female—and playing with the male—sexual organs continues through to Mona Hatoum’s chair with a triangle of pubic hair stuck to its seat, Helen Chadwick’s tumescent warty cucumbers cheekily ringed with fluffy fur cuffs and the bawdy sculpture of Sarah Lucas. A particular highlight is the room lined with the collaborative works of Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin, in which the classic headless female torso so beloved by old-school surrealists most emphatically gets her voice back.

Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017

Matisse in the Studio: Royal Academy, Sackler Galleries (until 12 November)

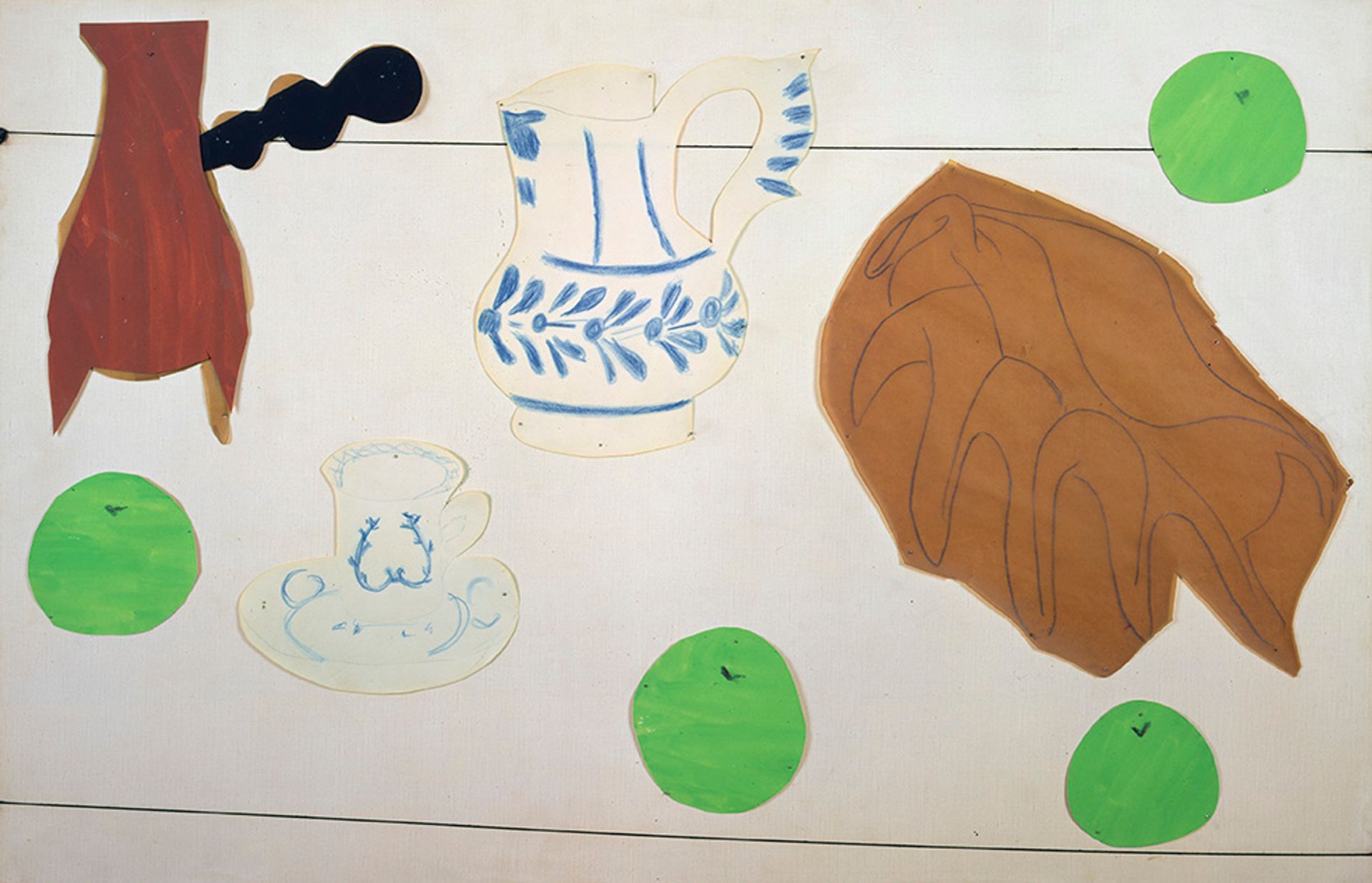

There’s certainly a frisson in seeing the actual furniture, textiles, sculpture and bric-a-brac that feature so prominently and repeatedly in Henri Matisse’s work shown alongside the paintings and drawings that they engendered. But this deftly curated exhibition is much more than a fetishistic relic-hunt or basic ‘compare and contrast’. It confirms how the objects with which Matisse obsessively surrounded himself in his various studio homes not only appeared as props in his paintings but also acted as inspirational triggers. We see the same chair, vase or sculpture offering multiple points of creative departure, cropping up again and again across decades and in often surprisingly different guises.

Revelatory moments abound. It becomes immediately evident that Matisse’s cut-outs owe an undoubted debt to the lacquered wood Chinese calligraphic panel—a 60th birthday present from his wife—which hung above his bed in Nice and which here is displayed above a parade of these late, great works. In another room African Kuba textiles owned by Matisse hang next to the vivid Red Interior. Still Life on a Blue Table (1947) and are the obvious inspiration for its all-over zig-zag composition. Placing the actual objects alongside the various reinterpretations of, say, Matisse’s silver chocolate pots or the gloriously bonkers shell-backed, dolphin-handled Venetian chair (which he described to the poet Louis Aragon as “the object for which I’ve been longing for a whole year”) provides a revelatory insight into how the artist’s mind worked and the rich range of creative possibilities he found in these often humble items. Not for nothing did the artist describe his possessions as “actors” and “a moveable library”, and it is a treat to be shown how they were made both to perform and inform.

The Henry Barber Trust, the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt, National Portrait Gallery (until 22 October)

Drawing is famously the most intimate and immediate of mediums, and nowhere is this more evident than in this compelling exhibition of Old Master portrait drawings—some of which have barely seen the light of day for decades—and which here have been especially selected to capture the direct encounter between artist and sitter.

This small jewel of a show presents works by some of the stellar names of the Renaissance and Baroque, including a male nude by Leonardo da Vinci from the Queen’s collection, a sheet of figure studies by Rembrandt and eight portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger. But name checking is beside the point in front of works that speak across the centuries, movingly evoking the living presence of these long dead and often unknown individuals, whether Holbein’s frankly gazing Woman Wearing a White Headdress (around 1532-43) or Annibale Carracci’s timeless portrait of his lutenist friend Guilio Pedrizzano (around 1593-94), whose handsome, dynamic vigour is conjured up by the merest, deftest strokes of the pen.

The whole gamut of humanity and human emotions is here. One minute I found myself rather embarrassingly close to tears in front of the awkward demeanour of a mid-16th-century young man, brought to life by an unknown Venetian artist, and the next laughing out loud at Leonhard Beck’s louche young man who sports a snazzy red cap and a woozy, dissolute demeanour. Again and again, in a multiplicity of media and styles, the highly personal spark of engagement between portrayer and portrayed is electrifyingly conveyed.