There was a sombre but celebratory mood at Studio Voltaire last night (6 September) during the preview of Putti’s Pudding, the first showing in the UK of drawings by the Italian artist Vittorio Scarpati.

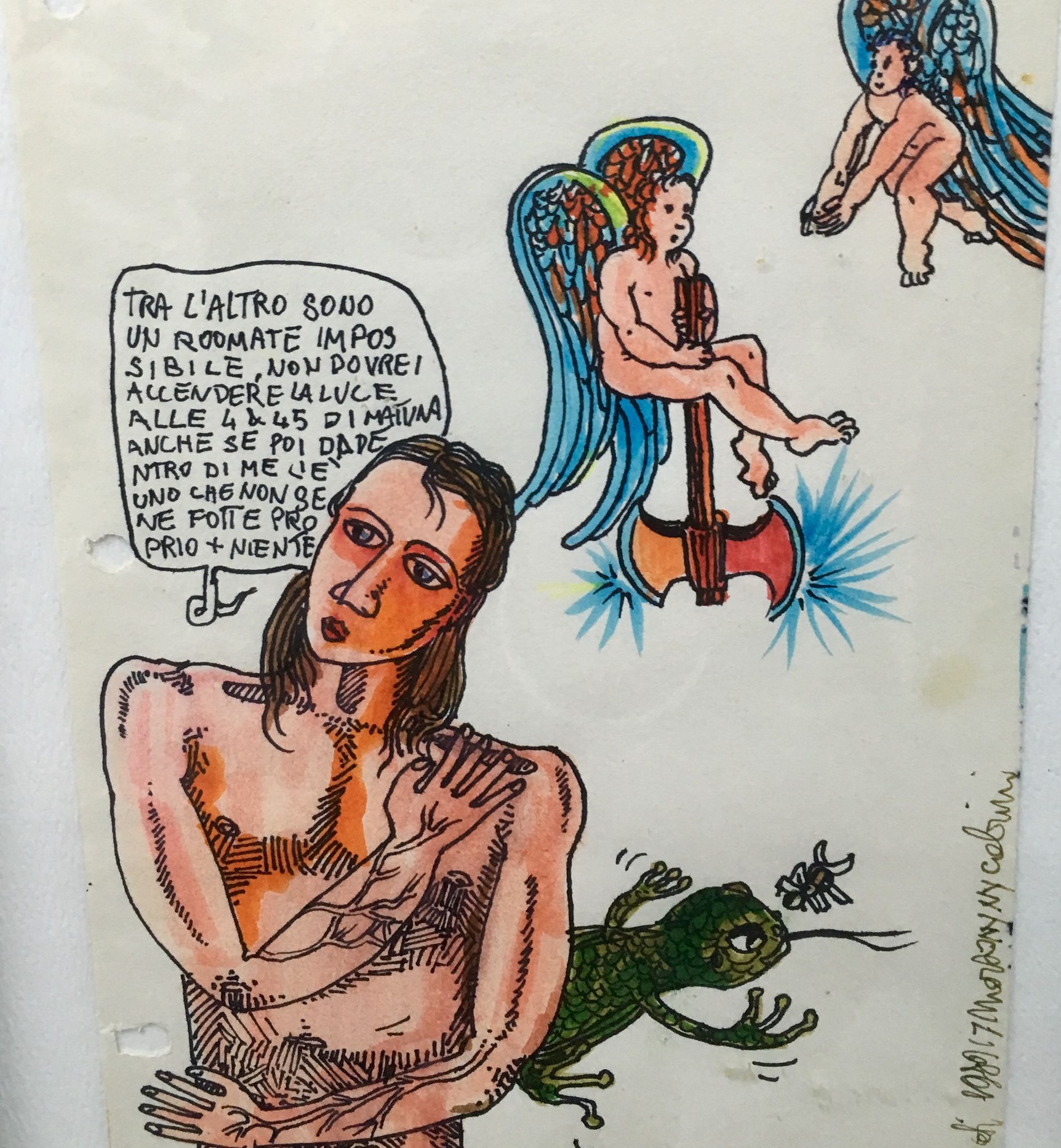

The works in the show were made from Scarpati’s hospital bed in the months before his death from Aids-related complications on14 September 1989. This sometimes savage but never sentimental visual record of a life cut short, is vivid, animated and often very funny while at the same time being heart-wrenchingly sad.

Vittorio Scarpati

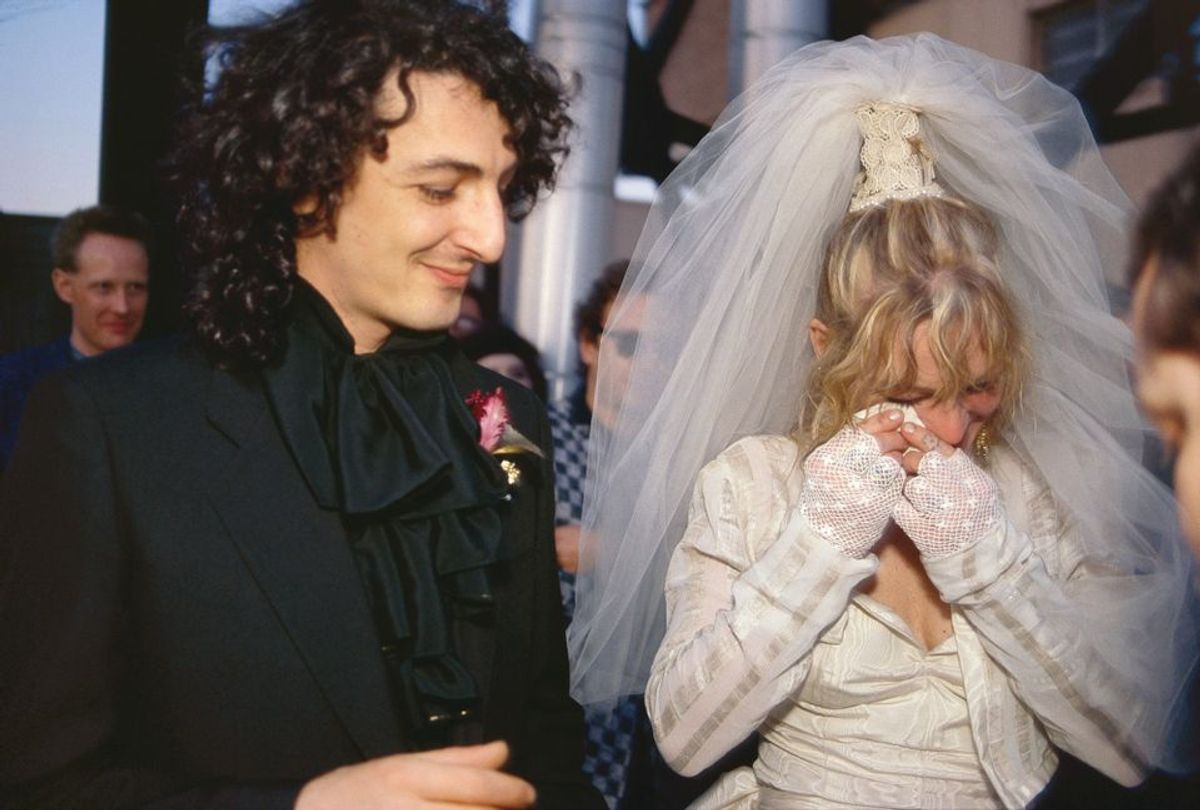

It is also a chronicle of a lover’s dialogue, with a number of the drawings accompanied by short texts written by Scarpati’s better-known wife, Cookie Mueller. The writer and cult figure of New York’s downtown scene, Mueller is immortalised both in the early films of John Waters and the photographs of Nan Goldin. Mueller only outlived her husband by three months and died from Aids-related illnesses on 10 November 1989. (At the end, they shared a room in New York’s Cabrini Medical Center.)

During an illuminating conversation between the exhibition’s curator Paul Pieroni and the writer Charlie Porter, we also learned that Scarpati’s three notebooks of annotated drawings from which this show is drawn are—so far—the only surviving body of work by this immensely talented and hitherto largely overlooked figure. Scarpati had worked as an animator, a graphic artist and a restorer of sculpture, but according to Mueller “just couldn’t bring himself to sit down and do his own work”.

Louisa Buck

This changed when Scarpati’s lungs collapsed and he was unable to speak. Friends brought him pens and drawing pads and he made some 300 works in three months, to the astonishment of all those around him—especially the doctors. As Mueller observed, “did he need to be physically tied down to finally do his important work?”

From the depths of his plight and in one of the last drawings in the show, Scarpatti writes: “HIV has decided to bless me. My life for good and for worse has had a series of uncontrollable spins, in which I complacently continue to rotate.” Mueller also emerges as a more nuanced and complex figure. As Pieroni puts it, “she was a party girl who also published in Semiotexte”.

These voices, emerging from the epicentre of the 1980s Aids crisis in New York—when discrimination was rife and the art scene and city changed forever—now seem especially crucial at a time when tolerance, creativity and a sense of community are all being assailed on both sides of the Atlantic.

• For more on this story, see On the side of the angels