The cataloguing of the art of Gerhard Richter (born 1932) has reached the years 1968-76. By this time an established international artist and leading teacher, he began to move away from the collective group activities of his early years. The period was also when Richter started painting series in different styles in fairly quick cycles. Blurred black and white photo paintings were superseded by colour variants, often with landscapes as subjects. At the same time, he was formulating abstract paintings of colour charts, painterly multicolour works and monochrome pieces. Fortunately for the reader, the paintings are listed in their different series as groups, so the sequence of images is not bewilderingly various.

Gerhard Richter: Catalogue Raisonné Volume 2shows Richter at his most Romantic and most austerely modern. Colour paintings of clouds, seascapes and landscapes are mostly derived from his own photographs. They are contemporary Romantic landscapes: plangent, attractive, absent of figures. Sometimes single compositions are combinations of different photographs. The landscapes are flat and resist any Romantic immersion of the viewer in an environment. They are not picture-postcard pretty, but landscapes as seen from car or train window or viewed from a hotel balcony. The paintings have the disappointment of holiday photographs that fail to capture majestic panoramas and instead produce something lacking energy, depth and intensity. In that sense, these are landscapes of the snapshot generation. This is not a failure on Richter’s part but a deliberate choice and an intelligent one.

Richter engaged with the Old Masters by painting versions of Titian’s Annunciation, obscuring the Virgin and angel under a queasy flurry of brushmarks. In later years, he approached Old Masters indirectly by lifting poses and echoing compositions. Another sequence of paintings treats the death of a tourist, mauled by lions. Among the missteps in this period are a number of photo paintings based on double-exposed negatives. These montage images are rarely exhibited. The puzzle is that an artist as astute as Richter thought they could work.

The famous 48 Portraits (1971-72) was Richter’s installation for the German pavilion at the 1972 Venice Biennale. It is a grid of 48 same-size paintings of black and white photo portraits of notable men. As an installation it was effective and memorable; individually, the paintings are uninvolving and visually unpleasant. Richter was aiming for an affectless and seemingly neutral array. Seen alone, the portraits are cursory and—strategic blurring aside—lack clarity. Perhaps Richter needed to take a detached approach to the paintings so as not to jeopardise the overall visual unity, but identical weaknesses are found in his stand-alone portraits.

Photorealism limits practitioners in the variety and emphasis they can use to adjust paintings in aesthetic and naturalistic terms. It is a conceptual approach that is about the relationship between painter and photograph, not painter and depicted subject. Richter’s early portraits fail because close adherence to photographic sources produces bad portraits. 48 Portraits succeeds as a conceptual piece even if it fails as a painting.

So various is Richter’s abstract work (which forms a majority in his output) that it is hard to quantify. Richter’s in-paintings (paint applied to canvas and mixed there until the surface is covered) and grey monochromes (with stippling and visible brushmarks) are process art. Process art is an approach which depends on viewers’ knowledge of the production process, which is as important as the visual content of the work that is—to some degree—arrested at an arbitrary stage.

Richter created large in-paintingswhich were made on multiple canvasesthat were hung together. After being exhibited, the separate canvases were dispersed to various collections. This was an obvious development from Richter’s habit of working in series, especially on sequences of abstract paintings.

The gestural evocations of foliage seem to come from action painting and Art Informel. Giant colour-saturated paintings of lush impasto details depicted in a smoothly photorealist manner are sensual and drily self-referential. The large colour charts with their squares or oblongs of discrete colours arranged in grids are related to hard-edge painting of the era. The colour-chart paintings are randomly selected pixels of colour that subvert the expectations of order and design that we search for in art, yet they are attractive.

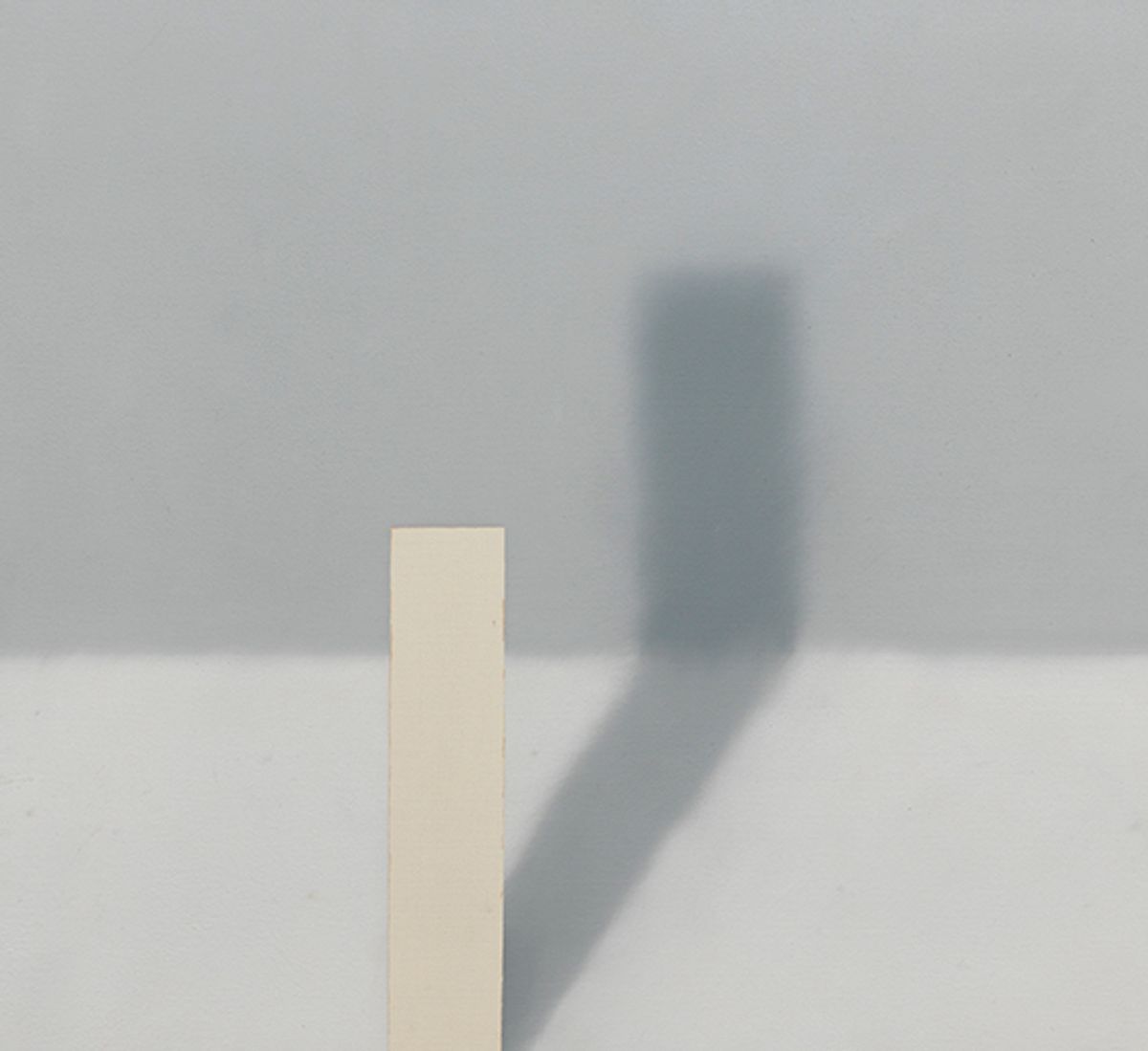

One of the least known groups of paintings is of simple geometric forms on canvas surfaces, which cast illusionistic renderings of shadows. They are conceptually elegant and visually satisfying. It is a shame that Richter did not pursue them for more than a few months. One of the drawbacks of Richter’s facility and stylistic variety is that he sometimes abandons an approach before he has thoroughly realised its full potential.

Viewing the grey paintings, one has the impression of a painter working through an idea to the point of ne plus ultra. Where some artists become locked into styles or methods, Richter has had the independence of spirit to be able to move sideways to new ideas. Due to the many underlying linking themes and approaches, Richter’s moves never seem like shallow opportunism or capriciousness. A network of intellectual sinews keeps Richter’s body of work connected.

As with the previous volumes in the catalogue raisonné, this one has introductory essays in English and German but English-only catalogue entries. It contains no discrete bibliography, only bibliographies and exhibition lists as part of entries. It includes sculpture and a handful of drawings alongside paintings, although there are no prints and only one multiple is listed. Illustrations are generous and clear. There are some comparative illustrations, showing works in the studio or exhibition. As usual in the Hatje Cantz series, the volume is impeccably designed, printed and bound.

• Alexander Adams is a British artist and writer. His latest book, London, Winter, is published by Aloes Books

Gerhard Richter: Catalogue Raisonné Volume 2, 1968-76, Nos. 198-388

Dietmar Elger, ed

Hatje Cantz, 656pp, €248 (hb, cased)