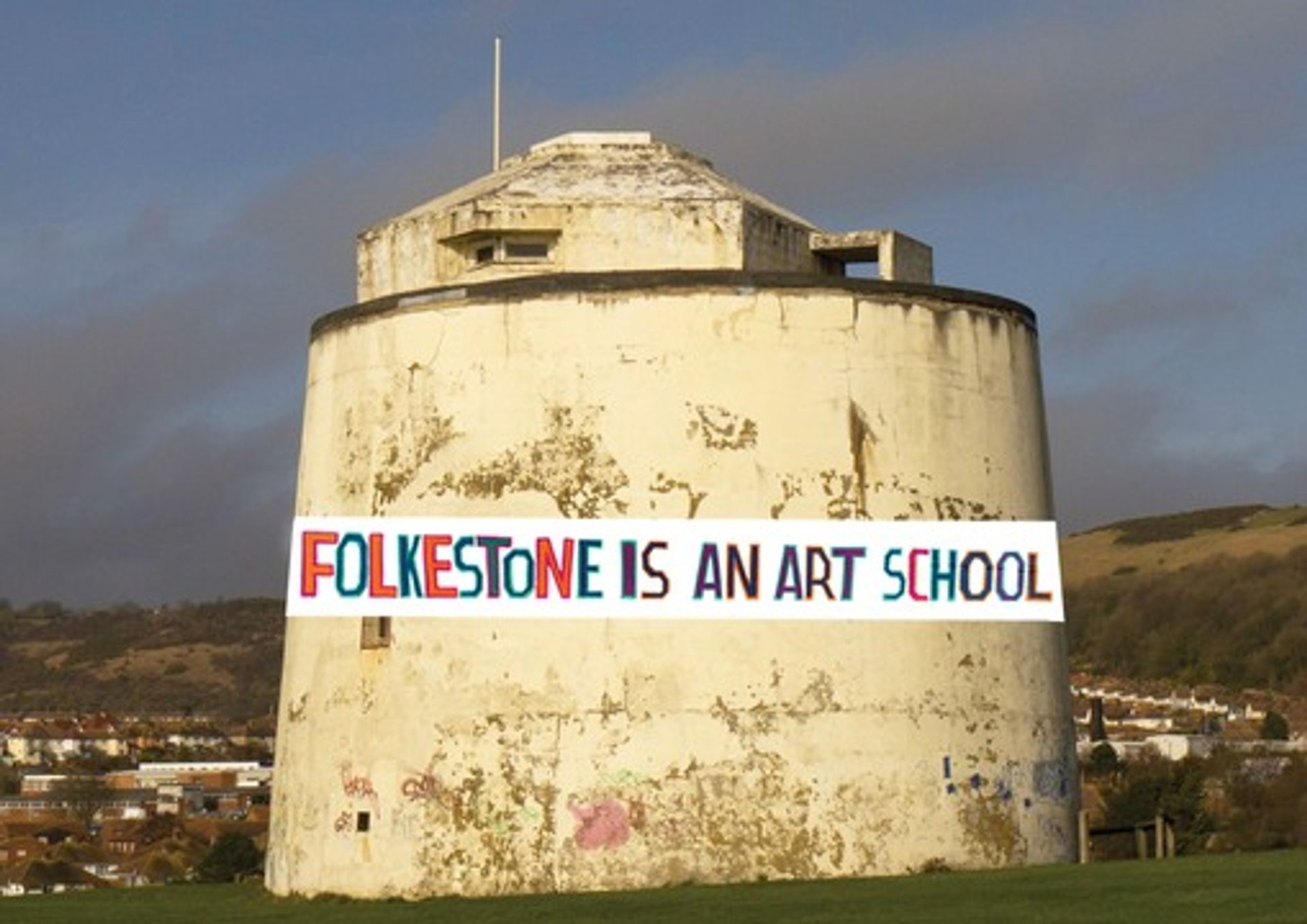

The fourth edition of the Folkestone Triennial, an exhibition of site-specific public art, includes artist-organised salsa dancing lessons, a floating house in the local harbour, and a declaration by Bob and Roberta Smith that the entire town has become an art school (see below).

The festive atmosphere is the result of years of investment. At the turn of the millennium, this town in Kent, in south-east England, was in a sorry state. “Folkestone’s grandeur is not so much faded as bricked up,” according to a 2001 BBC news report. The year before, the town’s cross-Channel port closed after almost half a century of dwindling fortunes. An article in the Telegraph newspaper declared that Folkestone “desperately needs investment and government funding, and these are, sadly, not forthcoming”. Its heyday as a high-end destination for British holidaymakers from the mid-19th century onwards (Charles Dickens called the place “delightful”) was long gone.

In 2008, with major financial backing from the chairman of the Creative Foundation, Roger De Haan, who is a local multimillionaire businessman, the triennial was launched to revive the town’s fortunes. “He was pretty certain that creative activity could be a way to change the atmosphere of the town, its economy and its look,” says Alastair Upton, the chief executive of Creative Foundation. The Creative Foundation’s first step when it was launched in 2002 was to establish a creative quarter “in the most rundown part of town”, Upton says.

Richard Woods's Holiday Home (2017) five-part installation (Photo: Thierry Bal)

Around £40m worth of capital went into buying and restoring property that “is now used for creative activities”, Upton says. “On any given day, there are 500 people living and working in the area.” The town itself has a population of around 46,000.

Developments like the creative quarter are a draw for artists and some are now settling permanently. The British artist Terry Smith chose to relocate from London 18 months ago as the capital is “becoming uninhabitable financially for many people”, he says. After considering Glasgow, Newcastle and even Venice, Smith chose Folkestone. “The Creative Foundation offers affordable rent and studio space”, he says, and there is “an extraordinary community of artists and people involved in creativity”.

Folkestone still has its challenges. The town remains “very rough around the edges”, says Simon Davenport, an artist who grew up in the town. But it is “changing every year as people realise the very obvious benefits of living here”, he adds. For this year’s curator, Lewis Biggs, one of those benefits is that the show is about the community. “It’s important to me that Folkestone Triennial is seen locally as a festival, as well as being an exhibition that attracts visitors from elsewhere,” Biggs says. The 2014 edition drew 135,000 visitors, who contributed an estimated £2.8m to the local economy.

“Documenta made the mistake in the 1980s of thinking that it didn’t need to bother with the people of Kassel, and the people quite rightly revolted,” Biggs says. “The 100 days’ programme [of events in Folkestone largely taken up by local residents] has been influenced by that revolt.”

Sol Calero's Casa Anacaona (2017) at Womad music festival before travelling to Folkstone (Photo: Jamie Woodley)

Antony Gormley's Another Time XXI (2013) (Photo: Thierry Bal)

A mock-up of Bob and Roberta Smith's Folkstone is an Art School (Photo: Thierry Bal)

WHAT'S ON

The fourth Folkestone triennial, which opens in September, features 20 artists including Antony Gormley, David Shrigley, Lubaina Himid and Amalia Pica. All apart from Gormley are producing new site-specific works.

For her contribution, the Venezuelan artist Sol Calero lived for a month in Folkestone to make Casa Anacaona, a tropical-coloured pavilion that will be installed on one of the town’s beaches. The work, co-commissioned by the Womad festival, was constructed with the help of an “amazing group of young people” from the area, Calero says. As well as activities such as salsa classes, the pavilion will also be a place “where people can just show up, read, even just basically hang out”, she says.

Bob and Roberta Smith’s work for the triennial involves a series of videos, banners and collaborations with locals to turn the entire town into an art school. Patrick Brill, who uses Bob and Roberta Smith as his pseudonym, says: “The town has already been transformed by art, but it has lots of problems which can’t reasonably be solved by a few art projects.”

Meanwhile, the British artist Richard Woods’s five-part installation Holiday Home (2017)—which will be spread across the town and includes a floating house in the harbour—was inspired by an estate agent’s leaflet looking for sellers in Folkestone, claiming there was a “booming” holiday-home market.

• Folkestone Triennial, various locations, 2 September-5 November

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'Triennial-at-sea returns to Kent coast'