Lebanon’s surprise museum boom shows no signs of losing momentum. Despite political paralysis and a refugee crisis driven by civil war in neighbouring Syria, there are more than half a dozen museum projects in the pipeline for the capital, Beirut. The latest addition to their ranks is the privately funded Beirut Arab Art Museum, which is set to become the city’s biggest art museum when it opens downtown in 2020.

The planned 10,000- to 15,000-sq.-m institution will house the 4,000-strong Modern and contemporary Arab art collection of the Beirut-based Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation. It will join the still-unbuilt Beirut City Museum, designed by Renzo Piano and backed by the Lebanese government, and the private, non-profit Beirut Museum of Art.

“There is enough demand to accommodate them all,” says Basel Dalloul, an IT entrepreneur and the managing director of the Dalloul foundation. “Lebanon is a cultural centre in the region and it has always been considered that way historically. Downtown is the traditional hub of Beirut and it’s accessible [to] everyone.”

While the location is still under consideration, Dalloul says the future museum will have temporary exhibitions as well as spaces for education, research and the conservation and authentication of Arab art. It will be free to enter, he says. He has ambitious plans to partner with international institutions including the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and London’s British Museum.

The foundation spends around $5m a year on acquistions and is considered one of the world’s largest collections of Modern and contemporary art from the Middle East. It is also actively lending pieces to major museums abroad. Four works by Dia Al-Azzawi were on show at the Mathaf museum in Qatar earlier this year and there are loans planned for 2018 exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Reina Sofia in Madrid and Tate Modern in London.

Dalloul’s father, the Palestinian businessman Ramzi Dalloul, began collecting almost 40 years ago in the hopes of building a legacy of pan-Arab art. “For years, people have only heard stories about death and destruction coming from the Arab world and forget that it is the cradle of civilisation,” Basel Dalloul says. “We’d like to show a better face of this part of the planet.”

With works spanning 150 years, the collection is mostly devoted to painting but also includes photography, sculpture, ceramics, video and conceptual art. Increasingly popular 20th-century artists such as the Egyptian Mahmoud Saïd and Lebanese Saliba Douaihy are represented, as well as contemporary artists who have achieved international recognition, including Etel Adnan, Dia Al-Azzawi and Mona Hatoum.

Ahead of the 2020 opening, the foundation is looking for other ways to share its art with the public. A collection database is expected to go online by the end of the year and Dalloul hopes to stage pop-up exhibitions in some of downtown Beirut’s vacant buildings next year.

“Our collection is quite unique in its quality as well as its diversity,” Dalloul says. “We look forward to educating and inspiring generations to come, not only from the region, but the world over.”

Three key works in the collection

1. Suleiman Anis Mansour

Jamal Al Mahamel III (2005)

This is one of the best-known paintings in Palestine, and arguably in the Middle East. With a title meaning “the camel” or “carrier of hardships”, the work is a larger version of the 1975 work that belonged to the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, thought to have been destroyed in the 1986 US bombing of Tripoli. The Dalloul foundation purchased it from Christie’s Dubai in 2015 for $257,000.

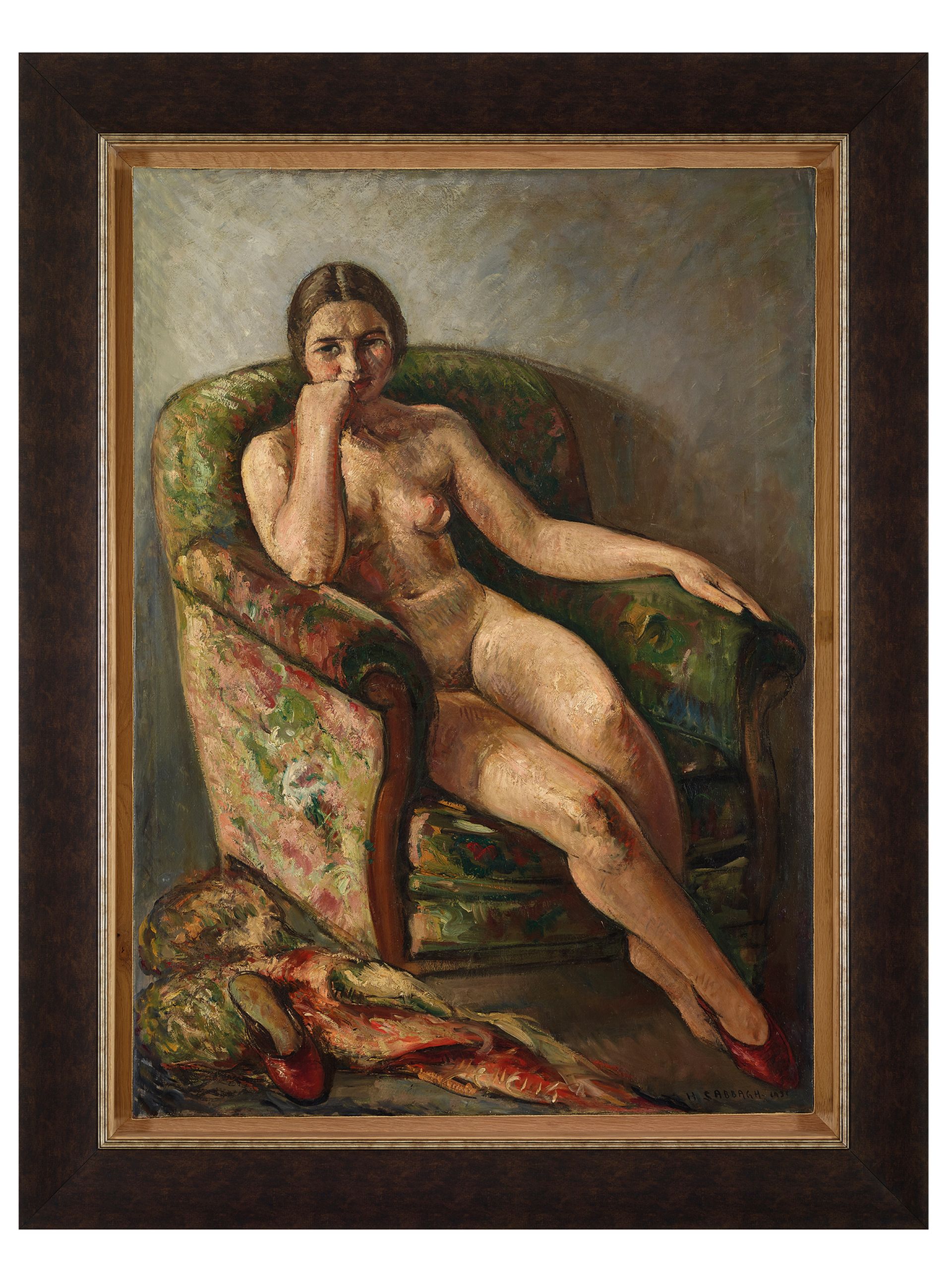

2. Georges Hanna Sabbagh

Nu au Fauteuil (nude in armchair) (1930)

The Egyptian Modern painter spent much of his life in France and was associated with the École de Paris. He worked in the European tradition of portraits, landscapes and nudes. “Beirut is a more open place than many in the region—we will be able to show a variety of subjects from nudes to political works,” Dalloul says.

3. Abdul Rahman Katanani

The Tornado (2015)

This three-metre-high sculpture was made by hand from more than 500 metres of barbed wire. It is a visual metaphor for refugees caught up in natural disasters. “This Palestinian artist could live anywhere but he chooses to live and work in the Sabra refugee camp to teach kids about art,” Dalloul says.