The French artist Sophie Calle's work almost always satisfies my basic requirements: that art has something to look at plus something to think about. She has worked across many media, but image, text and performance, often sub rosa, remain her principal instruments. She shows how dramatically viewer engagement and depth of content may vary when she—or anyone—tries to bring those dimensions artfully into tension. In the process, she continually re-weaves thematic threads of attachment, loss and surprise, of the irresistibility of time and of desire and its frustration.

The largest exhibition of Calle's work yet seen in the US, organised by the non-profit Ars Citizen, is on now view at the Fort Mason Center for Arts and Culture in San Francisco. Titled Missing, the event consists of four older projects staged in three buildings in a de-commissioned military base on a spectacular waterfront site, long since designated a national park.

Concurrently, Fraenkel Gallery's auxiliary space, Fraenkel Lab, brings visitors nearer to the present tense of her work with a selection titled My mother, my cat, my father, in that order, which wistfully (and a little wryly) documents three deaths particularly important to her.

The most extensive and engrossing project at Fort Mason, Take Care of Yourself (2004-07), has the largest venue to itself. Composed of dozens of texts and portrait photographs and a great bank of video screens, it was Calle's contribution to the 2007 Venice Biennale and makes concomitant demands on a viewer's stamina.

Like many of her pieces, Take Care of Yourself purports to draw directly upon her life experience. I say "purports" only because viewers today encounter this work against a political background of disinformation and sour scepticism, which have leached into American civic life. This context heightens one's alertness to the quotient of invention that even the most flatfooted documentation incorporates. Calle seems long ago to have intuited that such scepticism can benefit art in ways denied to journalism or memoir.

Regarded literally—and nothing in the work invites us to view it otherwise—Take Care of Yourself amounts to an epic act of public revenge for privately spurned love.

After receiving an unctuous, self-justifying e-mail breaking off a years-long affair, the infuriated artist handed out copies of the note to more than 100 women of her acquaintance and solicited their responses. They include creative personalities as famous as Jeanne Moreau, Miranda Richardson and Laurie Anderson, professionals in fields such as classics, psychiatry, law, literature and espionage, as well as a "teenage girl" and a "parrot."

The psychiatrist, a criminologist, a clairvoyant and an editor inferentially eviscerate Calle's lost lover's character. "Take care of yourself... because I won't be taking care of you" is what a family counsellor takes from the closing of the former lover's e-mail. A French intelligence officer renders the break-up letter in unintelligble code, while another interlocutor compresses the original into a more comic and strangled version.

The parrot—in fact, probably a cockatiel and presumably female—appears on video grasping a miniature printout of the letter, consuming it, then squawking "take care of yourself, take care of yourself" in French.

More than one respondent wonders, as many viewers will, about the final cipher in the e-mail: X. A farewell kiss, the writer's initial, a marker of the affair's ending?

Visitors will stagger out of this spectacle admiring Calle's productivity and the social dexterity implied by her many female relationships and her openness to so many moods and ambiguities. But we are also unsure whether Calle—or the persona that emerges from this hall of mirrors—is someone one would wish to know.

The burden of our ultimate unknowability by one another comes forward in other pieces, especially the multi-media elegy for her mother, Rachel Monique (2007), which occupies the Fort Mason chapel. Its centerpiece is a nearly still video projection of Calle's mother on her deathbed. It makes one queasy in its invasiveness and ambiguity—can we recognize the moment of death?—but the work is dignified by its place in a long history of final portraits that stretches back to antiquity.

Copies of a luxurious French edition of Monique's diary replace hymnals behind the pews. Subdued audio readings from it, in English, and framed texts and photographs on the walls and floor offer various angles of approach to Calle's memory and our imagination of the deceased. But the effect of this posthumous portrait, like those of related pieces at Fraenkel Lab, is to evoke our common bafflement by death.

The cognitive pessimism at the heart of Calle's work hits hardest in the small series of portraits titled The Last Image (2010), which is in Fort Mason's firehouse. In texts accompanied by photo portraits, people Calle met in Istanbul who had suddenly lost their vision to accident or disease describe their final visual memories.

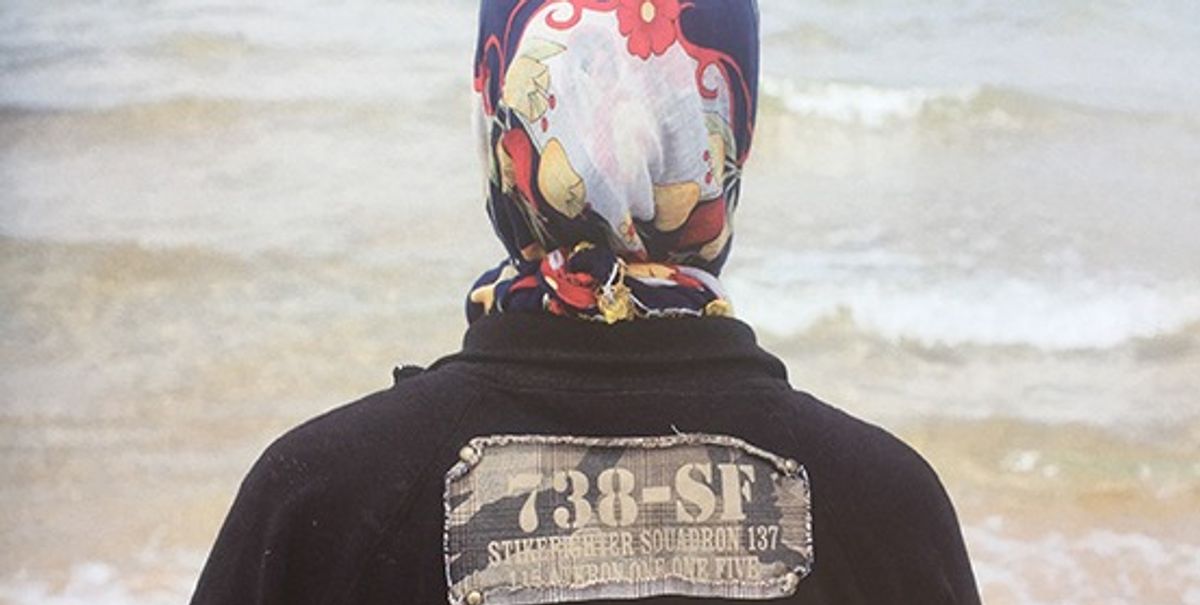

An accompanying work, Voir la mer (2011), offers video portraits on five screens of other Istanbul residents looking at the sea for the first time. Their responses, when they turn around to face Calle's camera, are inscrutable, owing to... what? Their inhibition? Our cultural distance? Wind-lashed San Francisco Bay, right outside the firehouse windows, intensifies the mystery.

Much conceptual art disturbs our sense of how different registers of information (static and moving imagery, text, etc.) function and interact. We see just enough in Missing to understand that the disruption extends to all information. What most disturbs is the difficulty of sharing our experiences.

Kenneth Baker retired in 2015 after 30 years as resident art critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. He is an Art Newspaper correspondent based in San Francisco

Sophie Calle: Missing, Fort Mason Center for Arts and Culture, San Francisco, until 20 August

Sophie Calle: My mother, my cat, my father, in that order, Fraenkel Lab, San Francisco, until 26 August