It’s a tight, close-up, black-and-white shot taken with a wide aperture, and the print itself is small: just three by six inches. In the centre of the picture is an ashtray, and inside it, a book of matches. Across the book, three unpunctuated words appear in sharp focus—WHY PICTURES NOW—which brings into relief the focal blur from which the phrase emerges. There is no way to tell whether the capital emphasis is orthographic or typographic: the typeface used is Copperplate Gothic, a 1905 font for which there exists no lower case. The letters appear obliquely, as the closed matchbook is propped up at an angle on the side of a spotless glass ashtray. This luscious photograph, diminutive in scale and wide in aspect ratio, formally cool and collected, essentially noir in content and cinematic in width, contains two further surprises. On the bottom of the ashtray, in riotous cursive script, the first three letters of “Hotel” are clearly legible: Hot. And the whole thing, in its nondescript position along the second wall of Louise Lawler’s survey at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), is framed in a slender rectangle of outrageous canary yellow.

Hot and cold, noir and yellow, small and wide, cursive and uppercase, centred and not—this tiny yet flamboyantly dialectical photograph is the titular anchor of this long-overdue exhibition of Lawler’s four-decade career. To linger on her placid photo-conceptualism is to find oneself awash in detail. There are no strident positions in Lawler’s work. Indeed, even in her anti-war positions (against Vietnam and Iraq, for example) the approach is more mordant than politically militant (one announcement card for a gallery event in 2003 drily promises “No drinks for those who do not support the anti-war demonstration”). But irony is less a language than an inflection in the way Lawler speaks. A compulsively funny, self-aware, near-fatalism suffuses her work, which documents the circulation and display of a certain body of high-profile (and financially viable) Euro-American Modernism.

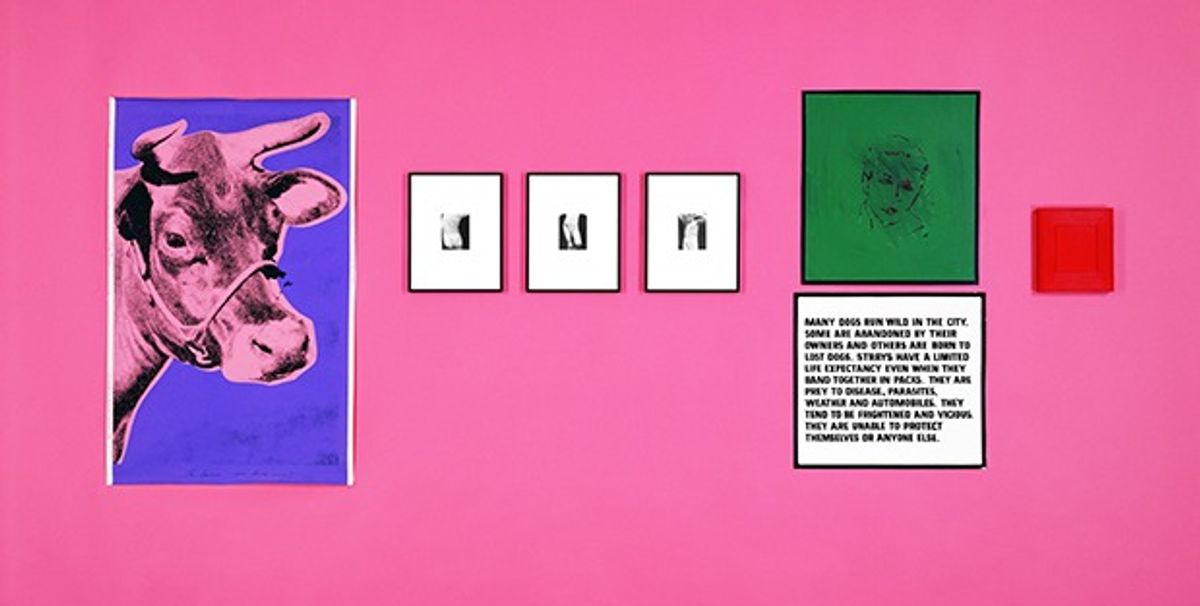

Deadlocked at the end of the 20th century, art (like capital or ideology) would seem for Lawler a fait accompli; it is already made, now it can only circulate. This sensibility is imbued by the market froth of the late 1970s and 1980s, the period in which Lawler emerged as an artist in New York. Then, as now, circulation was king. But in circulating through domestic interiors, auction houses, museums, galleries, magazines, films and advertisements, art, Lawler shows us, grows monstrous and strange, twisted and blurred. It is knotted in and by the world.

Such a sprawling endeavor invites freewheeling associations. Here is another: in the film based on Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (2000), there is scene of Wall Street anthropology in which bankers compare business cards. Paul Allen's has Copperplate Gothic as the font, which the filmmakers picked after their production designer recalled that a certain successful downtown gallery used the font for its logo. Although no account names it, the gallery in question must be Mary Boone's, who by 1981 was renovating a truck garage to fit her stable of big, bad painters not far from where Lawler had her first exhibition with Metro Pictures in 1982.

Lawler is no stranger to these linkages between culture and industry, art and capital. In 1982, she photographed works by artists including Robert Longo and Frank Stella at the brokerage firm Paine Webber. At least four images result, including Arranged by Donald Marron, Susan Brundage, Cheryl Bishop at Paine Webber, Inc., NYC (Adjusted to Fit) (1982/2016) and Untitled (Reception Area) (1982/1993). It's at least four because the first work belongs to Lawler’s “Adjusted to Fit” series, where she torques and stretches pictures to fit exhibition walls, so that a single photograph comes to have infinite permutations. The series is an elaboration of the anamorphism—the warping—that Lawler first introduced in her paperweight works of the early 1990s. In those, a crystal dome sits atop one of her photographs, so that the underlying image is distorted when viewed from above or flickers in bulbous fragments or vanishes entirely, depending on one’s vantage point.

Stepping back into the wider arena of the exhibition, we recognise that Louise Lawler has designed a business card for Dan Graham (1979), announcement cards for exhibitions, invitations, posters, postcards, publications, gift certificates, miscellaneous stationery and matchbooks—so many matchbooks. Much of this ephemera is in the last of four galleries of Lawler’s exhibition, dominated by displays of her printed ephemera. Before that, there are dozens of her photographs of works by other artists, stretched-to-fit wallpaper versions of those photographs, a handful of paperweight sculptures and a suite of “collaborations” with artists including Cameron Rowland, Allan McCollum and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The title of one work offers a self-consciously comedic summary of Lawler’s method and the influential community to which she belongs. It is named The Presentation of a Photograph of Louise Lawler Presenting a Work of Lawrence Weiner Presented by Documenta 7 Based on a Photograph Used by October Magazine to Illustrate an Article by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh to Participate in an Exhibition at Franklin Furnace Curated by Robert Barry and Viewed by a Public (1983).

Given this ferment of (re)production, it is no surprise that Lawler’s work has been interpreted through Walter Benjamin’s essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935). That reading, by Rosalind Krauss in a 1999 essay, accurately situates the conditions within which Lawler has worked. But we would do well to remember another point made by Benjamin in his earlier essay, A Short History of Photography (1931). Recounting the French physicist François Arago’s 1839 speech on the uses of Daguerre’s then-seismic invention, Benjamin notes that Arago articulated this novel technology’s potential use in the construction of historical memory. After photographing the stars, Arago proposes that we turn Daguerre’s camerae obscurae downward. Here, Benjamin writes, “we find the idea of establishing a photographic corpus of the Egyptian hieroglyphs.”

This is an intended procedure in Lawler’s work, which does, to some degree, record a historical corpus. For her, joining a gallery meant inheriting a readymade heritage not unlike the one made imperially available to Daguerre. But that earlier will toward total knowledge is gone; Lawler is much more uncertain than Arago was, and much more circular. In one of the few published interviews she has given, Lawler describes her process basically as an act of documentary feedback. “A gallery generates meaning through the type of work it chooses to show," she told Douglas Crimp of her first exhibition at Metro Pictures. "I self-consciously made work that ‘looked like’ Metro Pictures.”

In 1981, Crimp, one of Lawler’s most prominent interlocutors, wrote: “What Lawler’s photographs have shown is that institutional critique not only may be leveled at the impulse toward making pictures—‘Why Pictures Now’—but can take the form of a picture.” This is one of the least convincing yet common claims about Lawler’s work—that it is a form of institution critique—and it is unconvincing for a very simple reason: Lawler operates within a closed system of production, circulation and display; it's not in the outside position of critique, but the inside position of embodied reflection. The effect of this move can be critical, but it is not critique. Rhea Anastas moves the question along in her contribution to the MoMA catalogue: “I wonder whether Lawler’s reflexivity may be working differently, now that the conditions of the artist’s own reception are in forward motion at varying speeds or scales.” (The catalogue is rich, as is much scholarly writing on Lawler, and it follows an imporant 2013 October Files collection of critical writing on her work.)

Speaking of institutions and conditions of reception, it is worth attending to the ways in which MoMA's interpretation of Lawler’s work has changed between 1987 (when it held her first solo show at the museum) and 2017. In a brief essay by MoMA’s Cora Rosevear for Lawler’s 1987 exhibition, the artist is said to use “already existing works of art” to supply “insight into the external conditions of art display.” This remains an essential summary of Lawler’s procedure, which the museum still recognises. For the current show, curators have even allowed her to supply wall labels offering a sketchy and incomplete list of the corporate, institutional and individual owners of each edition, underlining her imbrication in the system that is the subject of her work.

But in the 1987 MoMA exhibition, no clear mention was made of Lawler’s feminist implications. The bibliography accompanying that show's catalogue did include Craig Owens’s 1983 essay The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism, but nothing more. This is one key way in which the museum has changed the way it presents her work. In the new exhibition, the point is made on the very first line of the very first wall text: "For the past forty years, Louise Lawler’s witty and slyly feminist work has raised questions about the cultural circumstances that support art’s production, circulation, and presentation."

In her essay for the catalogue, MoMA photography curator Roxana Marcoci adds significantly to the feminist account of Lawler’s practice. While a number of feminist discussions of Lawler’s work have appeared since Owens, Marcoci provides a vital and comprehensive reading. “Lawler has positioned her feminist work in relation to the economies of collaboration and exchange throughout her career,” Marcoci writes, noting especially her dedication to “undermining the idea of stand-alone authorial recognition.” But given Lawler's habit of rigorous institutional accounting, a discussion of how her feminism was elided by the museum’s 1987 catalogue (which, in its first paragraph, compares her to three tangentially relevant men: Michael Asher, Daniel Buren and Dan Graham) would have been good revisionist practice.

There are afterlives in Lawler, not only in the sense that forms by other artists survive in her work, but also that images, including her own, are necessarily seen through the metabolism of their circulation. When she stretches or torques her pictures for her wallpapers, she stresses the point. So it is not the mere corpus of cultural artifacts on hand but its metabolism that matters—the way art moves and is consumed, the way it breathes (ventilation is a recurrent feature in her photographs of interiors, as in a 1996 photograph of stacked ducts titled HVAC). Lawler’s scope is canonical—she generally looks to the established Post-war vision of Euro-American art history—but her method is anti-canonical, and in the slippage between these two lies much of her work's value, and its complications.

Mostafa Heddaya is a writer, editor and doctoral student in the Department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton

Louise Lawler: Why Pictures Now, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 30 July