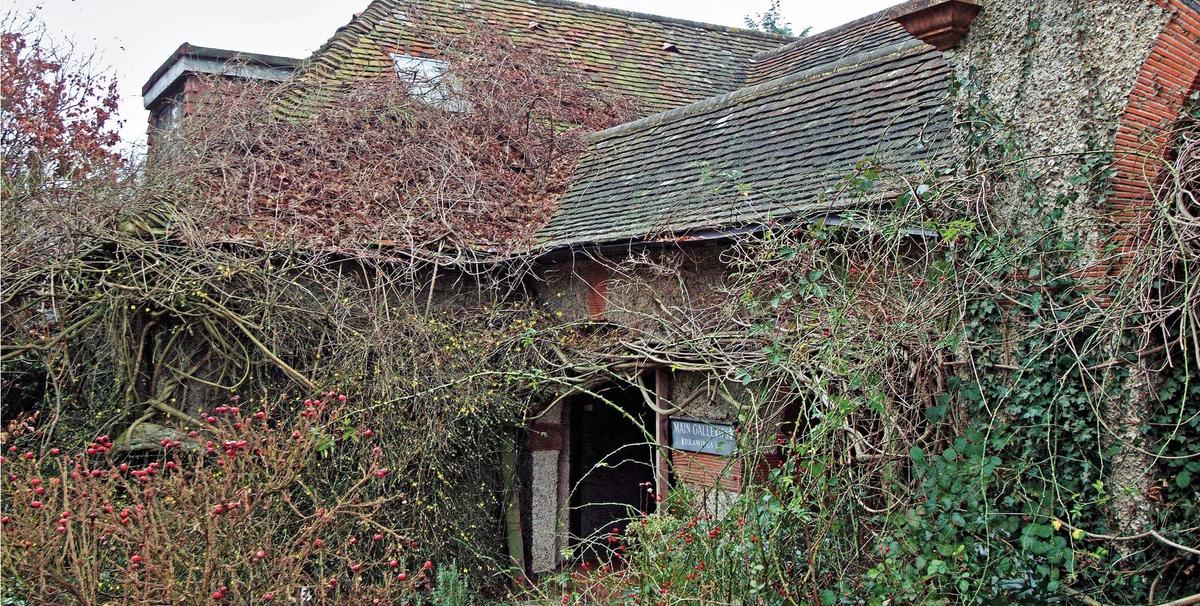

Some adored the Watts Gallery’s Sleeping Beauty look, but it was cold and dark, the roof leaked, the canvases sagged, and the tea room was poisoning its clients. What is more, few remembered its namesake, George Frederic Watts.

When he died in 1904, leaving in trust his art, gallery, studio, chapel and house in the Surrey woods, 40 miles from London, he was so famous that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had given him its first-ever exhibition of a living artist. But during the 20th century, the Watts Gallery became a picturesque relic, appreciated mainly by connoisseurs of Victorian art. In 2004, it was added to English Heritage’s “at risk” register.

Everything changed under the 12-year directorship of Perdita Hunt, who is leaving the Watts Gallery—Artists’ Village in July. (Alistair Burtenshaw, the current director of the Charleston Trust, will take the reins on 4 September.) She led the seven-year, £10m Hope project to restore the buildings (the chapel remains to be done), rehang the galleries and undertake conservation work on nearly all the art. Visitor numbers have risen from 10,000 to 65,000, the staff have gone from two to 50, while another 124 jobs are supported in the neighbourhood. An economic impact study by the University of Surrey in 2015 concluded that the institution contributed £7.7m to the UK economy.

Above all, the gallery has added energy, creativity and a sense of community to this part of southern England, known for its wealthy middle classes, but with hidden pockets of deprivation, and a large women’s prison, HMP Send.

This is how Hunt did it:

Find the right trustees There were eight when Hunt started; two could not imagine the kind of changes that were necessary, so they left, and she found four more with the qualities she needed. “Thank heavens I had Robert Napier, chief executive of a huge building materials company, when our builder went bust while the roof was off,” she says.

Develop a vision “I couldn’t just slap down a five-year plan,” Hunt says. “I had to ask, what is this place for? Why is it important? I went back to the founding vision of Watts himself: that the place would celebrate him locally, nationally and internationally, and fulfil his belief in ‘Art for All’.”

Fundraise, fundraise, fundraise “You have to believe that you can deliver the impossible and then you can convince others,” Hunt says of her ambitious fundraising campaign for the gallery. “Then, when you have everybody behind you, find out how much it will cost—and double it because things do go wrong.”

Her wide-ranging background, from the Heritage Lottery Fund and Arts Council to the World Wildlife Fund, certainly helped, as did the extreme need of the place. “There was raw sewage running down outside the building,” Hunt remembers. She secured funding from the Pilgrim Trust to pay for a new cesspit. Grants from the Lottery and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation enabled her to plan the Hope project properly and appoint a marketing manager—she had to remind the world who Watts was.

Hunt also took the controversial step of deaccessioning two works, by Albert Moore and Edward Burne-Jones, that were not part of the original collection, to raise £2m.

By a lucky break, the BBC featured the Watts in a television programme called Restoration Village in 2006. While the gallery lost the popular vote, it later won £4.9m of Lottery funding and raised a matching sum from five trusts and foundations, as well as many smaller donors.

Quality speaks, from the finish of the floor boards to the signage. It helps rope in the well-connected and well-off. Never serve bad wine.

Be relevant and idealistic “I asked myself, how can we express Watts’s moral purpose today?” Hunt says. She established an artist-led outreach programme for the women in Send prison, where participants are invited to respond to Watts’s works. “We give the prisoners canvases, paint, pencils, clay, and then we show their art in a selling exhibition at the Watts,” she says.

Avoid bureaucracy Bureaucracy is not efficiency. “We have just one staff meeting a week that never lasts longer than an hour, and one team management meeting,” she says. “Don’t do emails, because you can have a conversation and get far more out of it.”

• The writer is a member of the fundraising committee for the Watts Gallery—Artists’ Village