In 1963, shortly after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which Martin Luther King Jr famously delivered his I Have a Dream speech, a group of black American artists including Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis formed the Spiral collective in New York. Their first—and only—group show opened two years later and they disbanded shortly thereafter. But the questions the group raised—among them, are artists’ primary responsibilities to themselves, or to their communities?—remain open.

The founding of Spiral is one bookend of the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, which opens in July at Tate Modern. The other marker is the 1983 African-American Day Parade in Harlem, in which the artist Lorraine O’Grady handed out empty picture frames to attendees and invited them to imagine themselves as works of art.

“We’re asking, what were the stakes of being a black artist” in this period?, says the co-curator, Zoe Whitley. “And we put forward different answers to those questions through the artists’ own responses.” The problems raised in the era “extend beyond the bounds of race”, she says. Many of the questions raised are “ones all artists ask themselves every day”—including the question of whether art is a worthy pursuit.

The show includes around 150 works by artists such as David Hammons, Faith Ringgold and Betye Saar and includes paintings, sculptures, photographs and installations. The works come from an array of institutions. There are big lenders, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Menil Collection in Houston, but Whitley stresses that many items come from smaller museums such as the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. One highlight of the show, a painting by Jack Whitten titled Homage to Malcolm (1970), commemorates Malcolm X, but has never before left the artist’s studio for public view.

Whitley says the emphasis of the show is on the work itself. “This is an exhibition about art and artists, rather than a social history of art and ephemera,” she says. “The drive has been to look at what these artists have done as artists, not as civil rights activists or social historians.”

Next year, the show travels to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the Brooklyn Museum.

Lorraine O’Grady's Art Is (Girlfriends Times Two) (1983/2009) (Copyright Lorraine O’Grady)

TWO VISIONS OF AMERICA

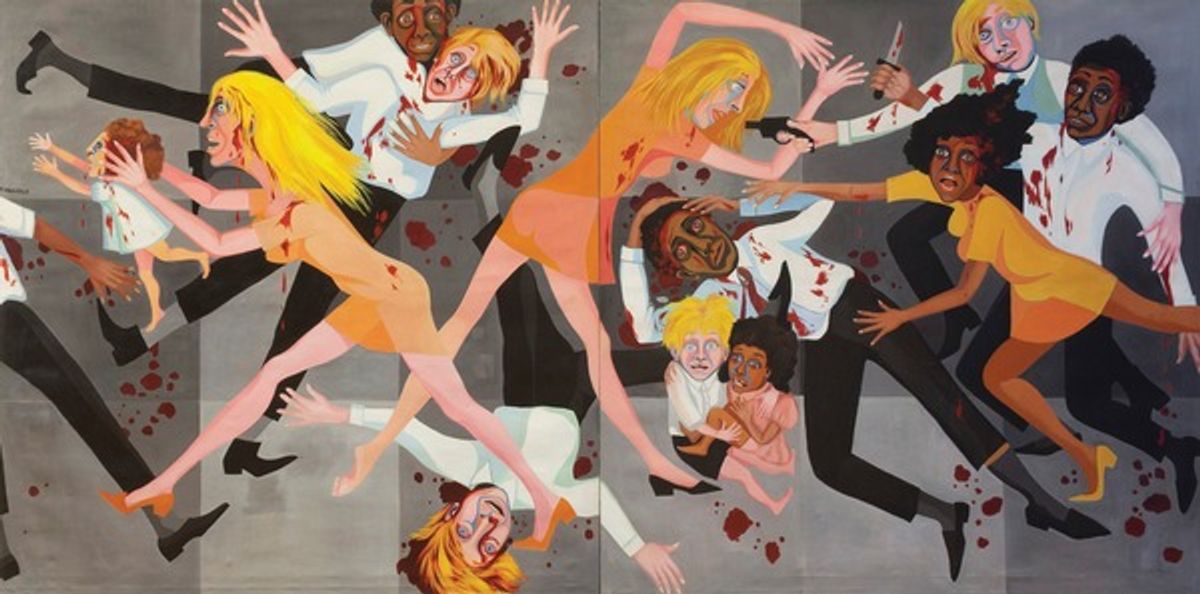

Faith Ringgold’s painting American People Series #20: Die (1967), top of page, was made at a fraught time. Although the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been signed three years earlier, racial tensions were still high because of white backlash against the measure. The pessimistic picture captures a mood of intense violence, although it has one small mark of hope: the black and white children who hold one another close in the centre foreground.

Lorraine O’Grady’s Art Is (Girlfriends Times Two), above, which is part of a project she undertook at the 1983 African-American Day Parade in Harlem, is altogether more optimistic. For the work, O’Grady handed out picture frames and documented parade participants posing not only as works of art, but also taking part in the creative process. The festive mood reflects a sense that there is always some reason to believe in redemption in America.

• Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Tate Modern, London, 12 July-22 October