Despite the arts having a reputation for being a difficult field in which to find employment, and recent high-profile staff cuts at major museums including MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum, institutional jobs overall are shown to be stable positions, according to the American Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD)’s 2017 Salary Survey, made public today (29 June). Two hundred and ninety-one museums in the US, Canada and Mexico (a 94% response rate) participated in the 2017 Salary Survey, a partnership between the AAMD and the global strategy consultancy firm Stax Inc, which examines pay and other benefits for 2016. It also compares data from 2011 to 2016.

“As a [museum] director, this survey is invaluable,” says Lori Fogarty, the director of the Oakland Museum of California and the president of the AAMD. “There are very few surveys that are as comprehensive” in terms of covering positions at every level of the museum organisation, Fogarty adds. The survey looks at over 50 staff positions in every department, from curatorial to museum security. It also compares salaries in terms of museum location and budgets.

This year’s survey reveals that museums spend a great deal of their operating budget on payroll expenses: for around two-thirds of the museums that participated, this was 41%-60% of their budget. It also shows that museums are a stable workplace in relation to the overall job force, with an average median salary rise of 3% in 2016 (greater than the US economic growth rate). And from 2011 to 2016, curatorial staff—an in-demand profession for nearly a decade according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics—had a salary growth of around 4.6%.

Meanwhile, in that same period of time, salaries of Chief Operating Officers had a compound annual growth rate of 5.5%, around twice the average increase for salaries across all departments. Fogarty says this may reflect the growing importance of such roles, as the complexity of business and operational areas—such as facilities, human resources and technology—make a “number two” leader necessary.

On the other hand, museum director salaries had a 1.6% rise in median salaries and a compound annual growth rate of 1.2%. One reason this might be, Fogarty says, is because museum directors often sign multi-year contracts with a negotiated salary. And perhaps they do not want to have huge disparities with the salaries of their staff, she adds.

The survey has many uses for museums, such as getting an idea of the “competitive salary landscape” when hiring new staff, Fogarty says. The other areas of compensation, such as paid vacation time and a flexible work schedule—which Fogarty believes are especially valuable to job-seeking millennials—are also important, since museums cannot always compete with salaries in other sectors, especially in places with a high cost of living such as the Bay Area, where her museum is located. It can also be useful when speaking with museum boards about budgets.

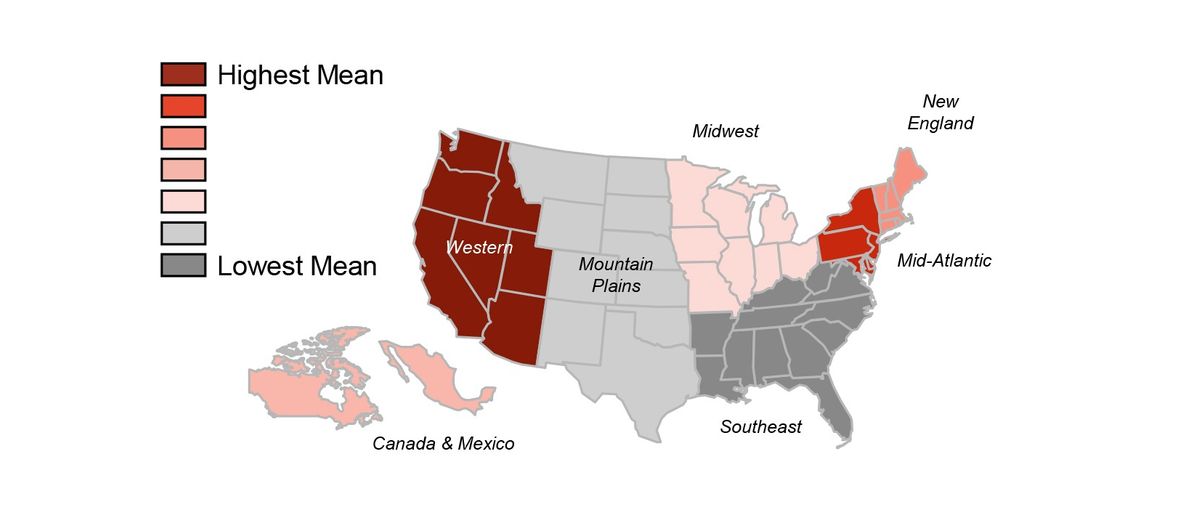

The breakdown also allows museums to compare salaries based on geographical areas, budgets and size, showing there really is no one-size-fits-all solution, Fogarty points out. For instance, the median salary for a chief curator or director of curatorial affairs in Mid-Atlantic states (including New York) was $168,600, compared to $93,846 in the Southeast, while the position had a median salary of $121,186 for museums with an annual operating budget of less than $1m, and $226,171 for museums with an operating budget over $20m.

The survey is also a useful tool for museum professionals, whether they are trying to negotiate a raise, or looking for new positions. Previously available for free to AAMD members, with a $100 fee for other users, the survey has been published without charge for everyone this year. This kind of research is “a big investment if you’re new in the profession and trying to understand what your expectations can be,” Fogarty says.

• The AAMD has been looking at data on museum salaries since 1918 (and has carried out a survey with a similar format to this year’s report since 1991).