After the previous edition of Pacific Standard Time (PST) closed in 2012, the Getty and the mayor’s office of Los Angeles held a celebratory press conference to share an economic impact report. Financial models were generated and revenues projected, including the extraordinary claim that PST had inspired $111.5m in visitor spending—hard to believe, considering that the initiative had little impact on museum attendance, according to a detailed Los Angeles Times analysis comparing numbers with the previous year’s figures.

Now, as the Getty and recipients of its $16m in grants ramp up for the second edition—Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA—devoted this time to Latin America and Latino art, PST leaders are getting back to basics. They are dispensing with claims of boosting cultural tourism and focusing on academic value. “The first time, we talked about the economic impact of PST a lot because we were uncertain otherwise of how to measure the success,” admits James Cuno, the head of the J. Paul Getty Trust. “But in the process of reflecting on it, we realised that success could be measured in publications produced and scholarship produced.

“We don’t want to overstate our claims,” he says. “But we think this will change art history by including in the canon much more Latin American art than what is usually considered.”

Cuno singled out one show, in the making for seven years, as particularly ambitious: Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, organised by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta for the Hammer Museum (15 September-31 December). The show includes 116 artists from 15 countries, some of whom have identified as feminists and others who, working in countries that have lacked an organised feminist tradition, are associated with left-wing, anti-dictator movements.

“This exhibition is about making visible an entire chapter in art history that has been made invisible,” Fajardo-Hill says. The show will do so along thematic lines, while the catalogue is organised by country to emphasise history and bibliography. Fajardo-Hill also hopes to publish a web resource to share their years of research.

The Getty museum’s own shows also promise to break new ground, from PST’s only antiquities exhibition (Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, 16 September-28 January 2018) to Making Art Concrete (16 September-11 February 2018), a survey of works from the collection of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. The exhibition will share insights gleaned from Getty conservation scientists working on objects by artists such as Lygia Clark, Willys de Castro and Hélio Oiticica.

As Gabriel Perez-Parreiro, the Cisneros Collection director, says: “Post-war geometric abstraction from Latin America is not unknown, but the industrial materials that artists used at the time are. We were labelling these things with absolutely no authority,” he says, describing how the media of Clark’s “cocoon” sculptures from the late 1950s, shown at her 2014 Museum of Modern Art retrospective in New York, were labelled inconsistently. Now, after spectrometry and other chemical analyses by conservation scientists, the Getty has identified the medium as nitrocellulose, which is commonly found in car-body spray paints.

Research in Brazil and Mexico

Video Art in Latin America at LAXArt (16 September-16 December), co-organised by the Getty Research Institute’s Glenn Phillips and the art historian Elena Shtromberg, is a sprawling show that involved research trips to over a dozen countries. Of these, Brazil is the best represented, with 13 of the around 60 artists included. Brazil also has the most artists in Radical Women, with 22 out of 116.

“It’s a huge country, with several centres of art: Sao Paulo, Rio, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte,” Fajardo-Hill says. “Also, women artists there have been freer to produce art. In other places it was so difficult to exhibit, they had to give up.” Shtromberg also credits Brazil’s museums, galleries and art schools, and praises the non-profit organisation Videobrasil for preserving so many works.

This Brazilian focus extends to other shows, like Axé Bahia: the Power of Art in an Afro-Brazilian Metropolis at the Fowler Museum (24 September-11 February 2018) and Xerografia: Copyart in Brazil, 1970-1990 at the University of San Diego (15 September-16 December), as well as to monographic shows, like Anna Maria Maiolino at the Museum of Contemporary Art (4 August-27 November) and Valeska Soares at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (17 September-31 December).

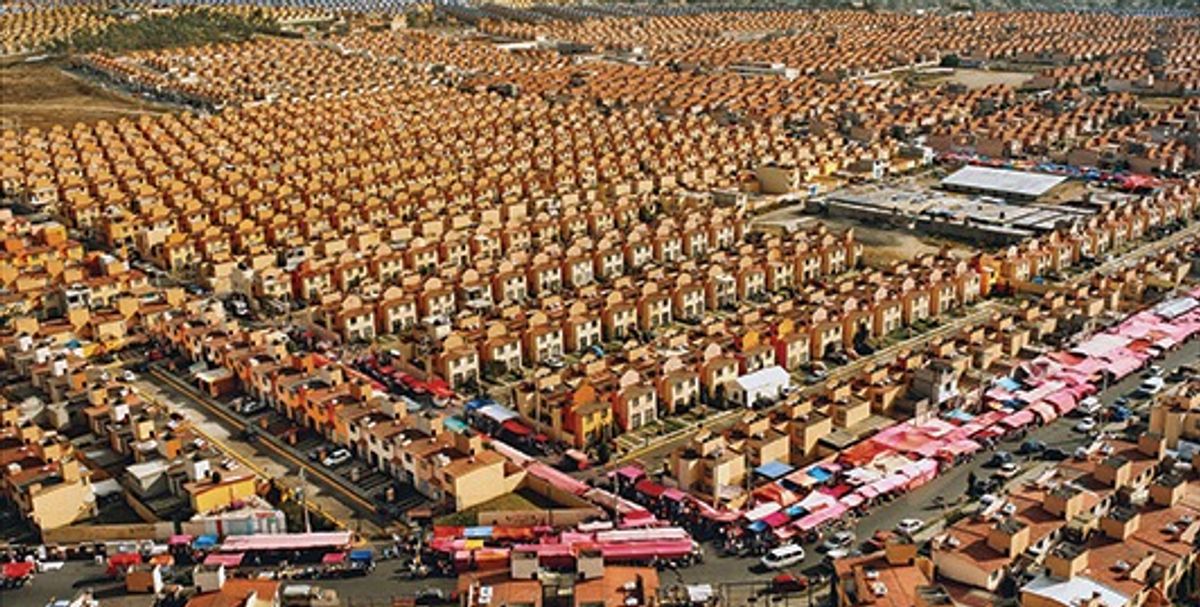

Mexico is another country that, naturally, will feature prominently across several PST shows. Perhaps the most ambitious are Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-85 (17 September-1 April 2018) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), and Lacma’s 18th-century paintings show, Painted in Mexico: Pinxit Mexici, 1700-1790 (19 November-18 March 2018).

The latter, due to travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in April 2018, focuses on a century that the curator Ilona Katzew calls “an ugly duckling” for the way it has been denigrated by scholars. Instead, she and her co-curators will unveil a mix of dramatic portraits, landscapes and lush religious paintings, some still owned by churches. Around 70% of the material, she says, had never been shown in a museum before, and most of those needed restoration. (While now marketed as part of PST, the show was not funded by the Getty because it was already in development by the time grant-making began.)

Chicano and Latino studies also stand to benefit, with over a dozen shows devoted to this area. One standout is Axis Mundo, organised by the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries (9 September-31 December). Axis refers to the broad network of queer Chicano art in Los Angeles that Edmundo Meza, an artist-activist performer and fashion innovator, participated in during the 1970s and 1980s.

Meanwhile, one of the most ambitious shows, Home—So Different, So Appealing: Art from the Americas since 1957 (until 15 October), organised by Chon Noriega, Mari Carmen Ramírez and Pilar Tompkins Rivas at Lacma, integrates Latin American artists with those of Latin or Mexican descent (known as Latino or Chicano artists) living in the US.

“This is probably the first show to say: we are looking at Latino and Latin American artists and not grouping them by nation, by generation or genealogical roots,” Noriega says. Instead, the show explores how artists grapple with emotionally and politically loaded ideas of home. Often, the artists use actual materials associated with domesticity—“not representations”, he notes.

Radical Women also shares this move to integrate Chicano/Latino art with Latin American art. Several experts note that integrating the two fields, which historically have been delineated and have found homes in different university departments, could prove important in itself.

Likewise, given the vast scope of the Getty’s overarching topic this time around, several PST shows promise to make connections between Latin American countries that are rarely studied together.

Ramírez, a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, who is perhaps the best-known US-based curator of Latin American art and who served as an adviser for PST, says: “We don’t have anything like a comparative history of Latin American art. But I think a number of these shows are moving in that direction by showing affinities among artists from different countries.” The initiative “has the potential to really shake up the field of Latin American art.”

But as for long-term effects, Ramírez sounds less certain. “I wonder whether all this activity will stimulate institutions to take the next step and make Latin American and Latino studies an integral part of their programmes in a systematic way, with curators dedicated to the area. That, for me, is the open question.”