Unlikely as it seems today, Paul Cézanne’s paintings were reviled for much of his lifetime, his portraits perhaps most of all. Soon after he died in 1906, his dealer and later biographer, Ambroise Vollard, bought the contents of the artist’s studio in Provence. While the still-lifes, landscapes and bathers found buyers—including an admiring Henri Matisse—the portraits lingered in Vollard’s stock. An exhibition of 24 of them at his Parisian gallery in 1910 was, until now, the only show ever dedicated to Cézanne’s portraiture.

On 13 June an exhibition of around 60 portraits spanning five decades of the painter’s career will open at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The relative neglect of the theme can be traced back to a preconception of Cézanne as a “quasi-abstract artist” that emerged in the early 20th century, says the show’s curator John Elderfield, the chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “What was most of interest were the works that seemed to amplify that—it meant that pictures with a human narrative were just less popular,” he says.

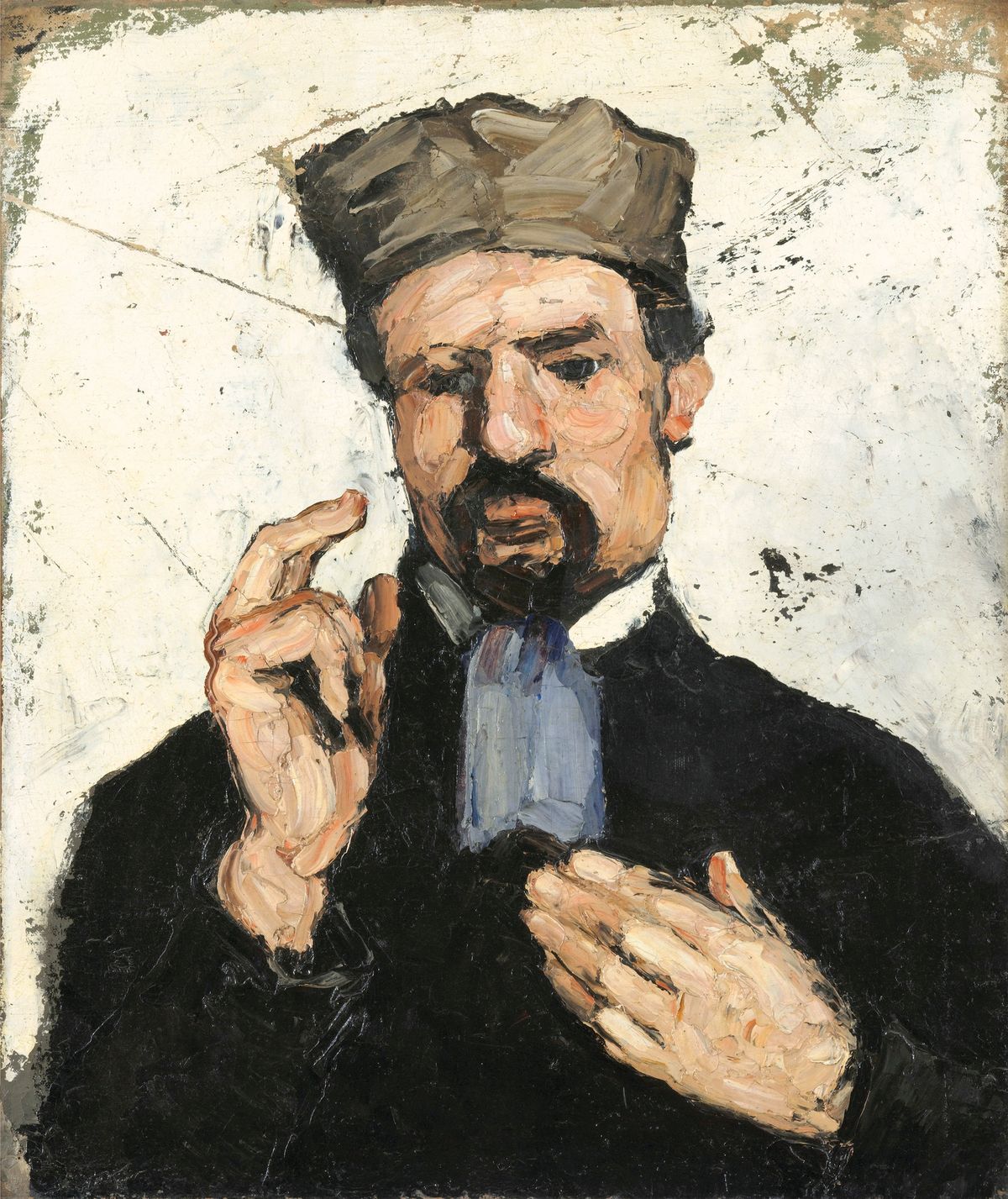

Cézanne treated his wife Hortense and his own prematurely balding head as recurring motifs, just like the more celebrated apples and the Mont Sainte-Victoire. By assembling chronological pairs and groups of related works, from the dark 1860s portraits of Uncle Dominique to the sympathetic 1900s depictions of working-class labourers, the exhibition will reveal how Cézanne returned repeatedly to the same inner circle of subjects. Using details of domestic decor and dress as footholds in addition to stylistic changes, curators stand “a better chance” of reconstructing the development of an oeuvre that he rarely signed or dated, Elderfield says.

Shunning commissions even during his final decade, when he was suddenly in demand, Cézanne was interested in capturing “presence more than likeness” in a portrait, Elderfield says. He experimented formally, sometimes painting from photographs and earlier paintings rather than from direct observation. “There’s this image of him as tormented, doubtful, slightly crazy,” Elderfield says. “The other side of him was calculating; he really thought clearly about making pairs and short series of works.”

• Portraits by Cézanne, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 13 June- 24 September; travels to the National Portrait Gallery, London, and National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC