Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901-91) may well be one of the most fascinating artists you’ve never heard of—that is, until recently. An exhibition of the late Turkish artist that is due to open at Tate Modern on 13 June and the recent of sale of her seriously large abstract painting Towards a Sky (1953) for just under £1m (nearly twice its low estimate) is generating a buzz both around Zeid’s work and her incredible life story, which has all the makings of a feature film.

Born into an elite Ottoman family, she experienced her first (of what would be many) tragedies at the age of 12 when her older brother was convicted of murdering her father. Zeid turned to art as a way to cope. She would later buck social conventions to become one of the first Modern female painters in Turkey and a pioneering figure in the abstract art movement, who worked on a scale that was ambitious by anyone’s standards, and exhibited regularly in her native country as well as in France and the UK. Despite this, she remains a relatively obscure figure in the art-historical canon. The exhibition at Tate Modern sits with the institution’s mission to reassess the work of overlooked artists from outside Western Europe and North America and follows earlier shows on the Lebanese painter Saloua Raouda Choucair and the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El Salahi.

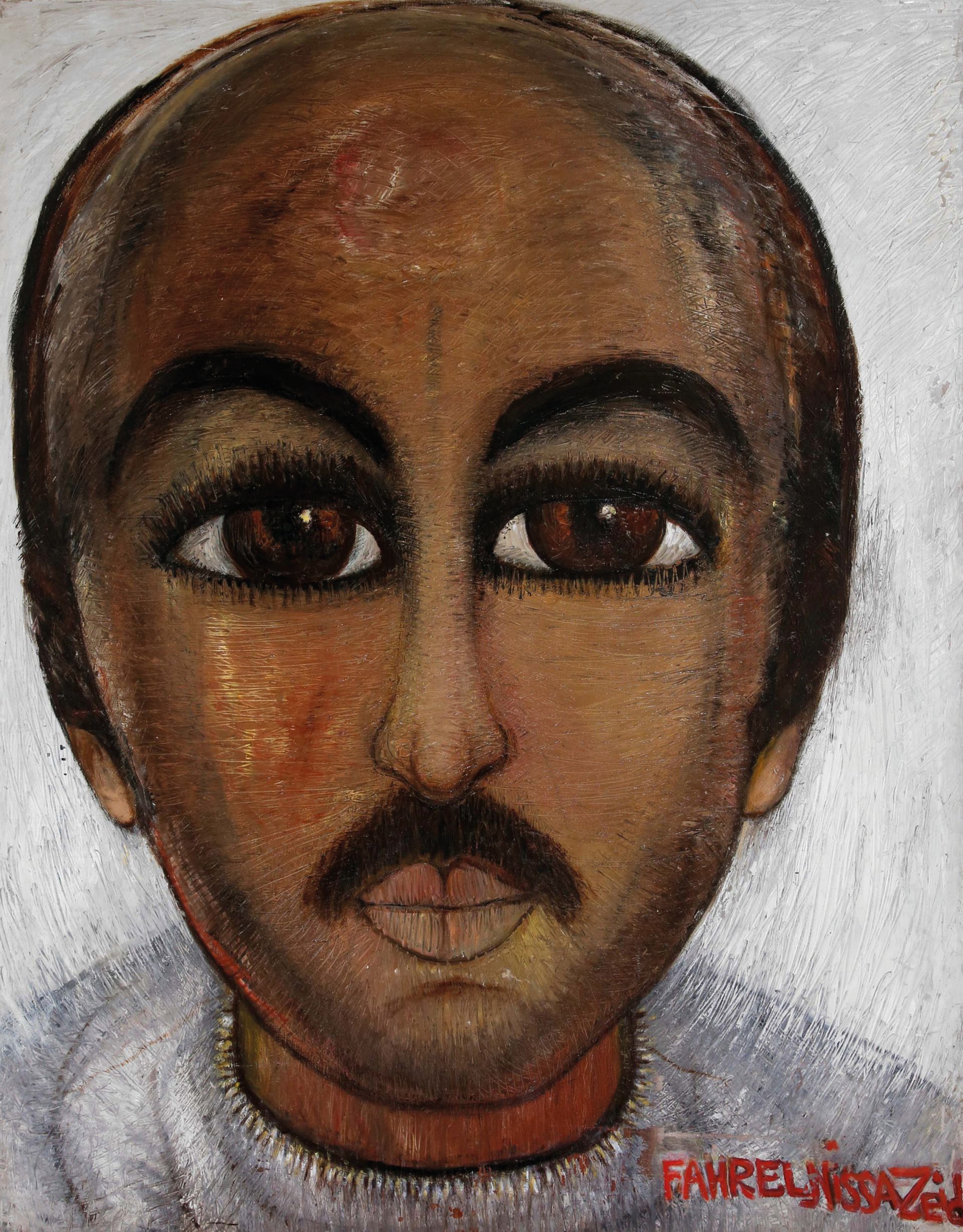

“She had a fantastic career from the late 1940s to early 1970s in London and Paris and yet has been completely written out of art history,” says Kerryn Greenberg, the Tate’s curator of international art and co-curator of the show. The exhibition traces Zeid’s expressionist beginnings through to her interest in abstraction, which arose from her first plane flight over Baghdad, to her foray into sculpture and return to portraiture late in life. Visitors can expect to see several of her bold, large abstract canvases such as My Hell (1951), which was shown at London’s Institute for Contemporary Arts in 1954, as well as early and late self-portraits. Emphasis is being placed on the internationalism of her career: she immersed herself in the art scenes of Istanbul, London, Paris (where she was part of the critic and curator Charles Etienne’s group) and Amman.

Her marriage into the Iraqi royal family meant that she moved within the upper echelons of society. The diplomatic postings of her husband, Prince Zeid bin Hussein, allowed her to mix with a staggering array of people, including Hitler (legend has it they discussed art when her husband was ambassador to Germany). The military coup in Iraq in 1958, which resulted in the assassination of Prince Zeid’s family, led to a drastic change in circumstance for her and her husband, who were living in London at the time. It was at this time that she began to create what she called her “paléokystallos” sculptures, made from painted chicken bones, which she cast in resin and placed on turntables so they could rotate. A few of these will be in the show.

Larger-than-life figure The Tate sent conservator Natasha Walker to Jordan, where Zeid spent her final years, ahead of the exhibition to stabilise ten paintings from the Zeid family collection—a major lender to the show along with Istanbul Modern. After conducting a condition check on the works months earlier and determining that only minor treatment was required, Walker returned to Amman armed with a suitcase full of supplies and set up shop in the home of Zeid’s son, Prince Ra’ad bin Zeid. She soon found herself regaled with hundreds of anecdotes about Fahrelnissa. “She was a truly larger-than-life figure,” Walker says. “She was eccentric and very colourful and that comes across in her work. She was not the most meticulous painter and did not always bother to finish things like other artists. [Her work] is more spontaneous.” Walker heard tales of Zeid being in a trance-like state while painting, emerging hours later exhausted with no memory of what had occurred around her.

Rough treatment Whenever she moved home, her paintings went with her and her desire to surround herself with her canvases has left its mark. The treated works showed signs of having been handled and moved around a lot. “They were in Berlin, Baghdad, Paris, London and Amman, all of which have very different climatic conditions,” Walker says. “They were regarded more as personal possessions so may have been wrapped in a rug or bubble wrap, whereas now we put them in climate-controlled, foam-lined packing cases to protect them from fluctuations in relative humidity and temperature.” As well as issues such as unstable paint brought on by climatic change, the pieces also suffered from small tears or dents—typical of the type of wear and tear often brought on by being propped against furniture. Zeid’s Paris studio was so packed with art and other things that her family jokes that there was not even room for a razor, Walker says.

Zeid’s own less-than-gentle treatment of her works also has had an effect. Photographs show how she nailed her large abstract paintings, as much as six metres tall, to the wall and tacked others to the ceiling. She was also known for a peculiar party trick that involved unfurling her large canvases to create a red carpet from the gate to her front door. “The only way for guests to get into the party was to walk over the canvases,” Greenberg says. “She was actually quite rough with the works herself.”

But these traces of past use are part of the works’ history and something that Greenberg says they were keen to retain, unless they posed a threat to the work. “We are not seeking to tell a different story. We want that life to be part of the life that the pieces communicate; we’re just trying to stabilise them,” she says.

“She was a pioneer in so many respects,” Greenberg says. “She pretty much turned all of the stereotypes and standard conventions on their head and did pretty much what she wanted to, which took a lot of courage and determination and gives you an indication of what kind of person she was.”

Walker says: “Later in her career she wanted recognition. Maybe earlier in her lifetime, [art] was something she enjoyed doing and she got a lot out of her occupation but later she wanted to be recognised.” The Tate show is sure to bring the overdue name recognition she craved.

• Fahrelnissa Zeid, Tate Modern, London,

13 June-8 October