How does it feel to cross the desert from Mexico into the United States while being hunted by US border patrol agents? To leave behind your family, friends and the only life you have ever known in the hopes of finding a better future? Or to flee violence and terror back home only to be terrorised once again by the experience of trying to enter America?

A new, hugely ambitious, virtual reality project by Alejandro G. Iñárritu, the Oscar-winning film director of The Revenant and Birdman, strives to recreate the fear, anxiety and uncertainty experienced by migrants on their long, exhausting journeys.

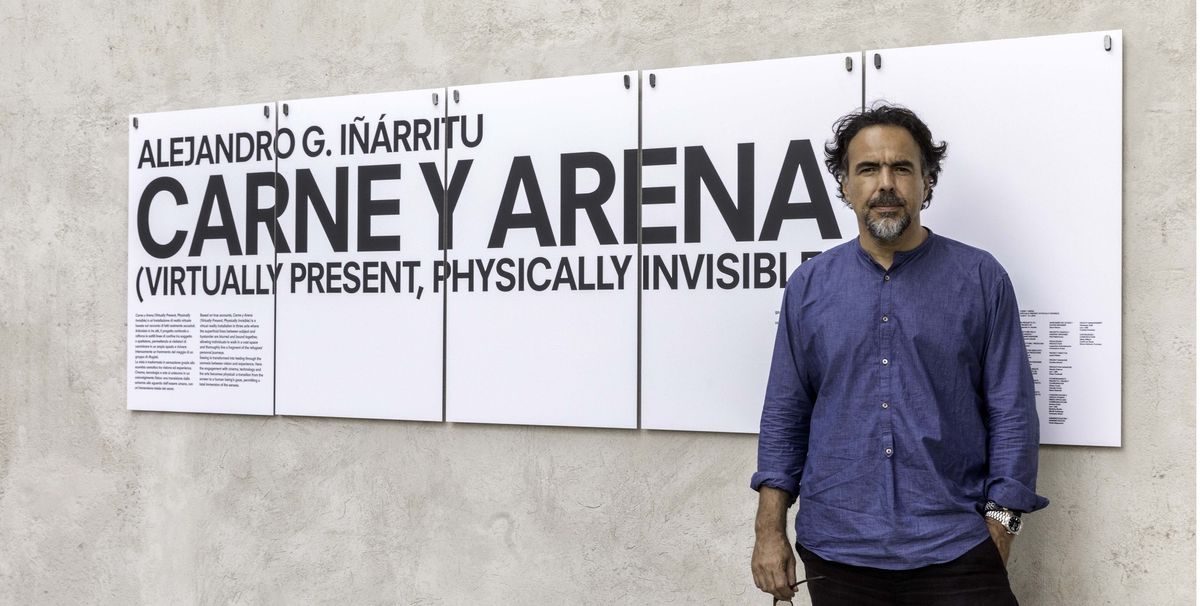

“We are all completely desensitised” to the desperate stories of refugees and migrants, Iñárritu told The Art Newspaper at the Fondazione Prada in Milan where the work, entitled Carne y Arena (Virtually Present, Physically Invisible), opens to the public this Wednesday, 7 June (until 15 January 2018). “We read horrific news almost every day about another boat with hundreds of people on board sinking [in the Mediterranean] and we just dismiss it. This is an attempt to convey something that I think we have lost the ability to feel.”

The experience begins in a darkened room which recalls the cells used to hold migrants and refugees apprehended coming into the US. It is strewn with shoes and other objects found in the Arizona desert near the US/Mexico border where 6,000 people have died attempting to cross. You enter alone; directions on the wall instruct you to remove your own shoes and wait for an alarm to sound. Then you proceed barefoot to the virtual reality chamber. The floor is covered with sand so that when the virtual reality film begins you feel as if you are walking through the desert at night alongside exhausted and scared men, women and children. Before long, a helicopter with a spotlight tracks you down. US border agents follow, point a machine gun in your face and shout instructions at you and those around you. Their barking dogs strain at their leashes to get at you. The noise is overwhelming, the effect terrifying.

“There’s a moment when your identity shifts a little bit and you lose the ability to rationalise what you’re experiencing and that’s the beauty of it: you start reacting with your heart and your emotions and not with your brain. That’s what I’m interested in,” Iñárritu said.

On the journey you hear snippets of the migrants’ stories. “Why do you speak such good English?” a border agent shouts at a young man. “I’m an attorney” answers the migrant. After the virtual reality experience is finished, you pass through a display where all the migrants who took part in the project tell their own stories and you learn that this young man is Luis, now 36, originally from Mexico, who was the first undocumented immigrant to graduate from UCLA Law school.

Iñárritu met Luis and the other migrants and refugees who participated in Carne y Arena through Casa Libre in Los Angeles, a shelter and advice centre for unaccompanied immigrant and refugee children run by the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law. He then set up a theatre workshop to help them work through their experiences in a safe environment before taking them to the desert for filming.

The challenges were immense: Iñárritu was directing non-actors and using new technology to try and create a narrative which is “precise and coherent and incorporates many different storylines in one space in a 360 degree experience,” he said.

The resulting work, created with the cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and funded and produced by the Fondazione Prada and Legendary Entertainment, humanises the very same desperate migrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries branded “bad guys” and “rapists” by President Trump. In so doing Iñárritu, who is himself Mexican, has arguably created the first great, anti-Trump work of our time. But he finds the description reductive.

“I hope it’s not read like that because I never thought of Trump [while making it]… we have made such a small, horrendous, embarrassing human being big by discussing him so much. We have to look deeper at the problems that drive these people to leave their countries, the government and corporate corruption, the amount of drug addiction and consumption, the supply of drugs by my country to the United States, the guns, and the money that corrupts the fabric of social things. The migrants are the victims of all these circumstances. Trump is just the tip of the iceberg…I started thinking about this [project] four years ago when he was just a clown on tv.”

New art form

Carne y Arena “is not cinema”, Iñárritu said but is an entirely new art form which has the potential to “shake the whole world.” Although virtual reality will inevitably be used for “stupid things” like video games and porn, “once artists start finding a fresh language for it, I think it will be something that can say things in a different way, that can submerge you in a completely sensorial experience.”

Cinema has lost some of its power to impress us, Iñárritu added. “One hundred years ago it was incredibly relevant and it could really shake people.” But we have lost some of our innocence in that sense.”

Meanwhile, “museums have become a little bit boring and elitist and predictable and it’s hard to experience real, disturbing emotions in them.” And the art world has been “polluted” by money, Iñárritu said. But a virtual reality experience can be pure. “You can not buy it, you can not take it home, it’s something that you experience. I love that. This is just somebody's imagination shared by you in a real-time moment. Nobody can corrupt it, nobody can own it. And that’s lovely.”

Asked if he might use virtual reality again, Iñárritu said that he “would love to” adding that he has “a couple of ideas” and would like to invite “friends of mine, artists I admire, to use the medium and explore its possibilities.” He named James Turrell, Olafur Eliasson, Anish Kapoor and William Kentridge as artists he would like to see working with virtual reality. “Can you imagine what an artist working at that level could do?”

Coming soon to a museum near you

Carne y Arena premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May and will open at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on 2 July. It will also be shown at the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco in Mexico City from August. It will likely travel to other cities too, Iñárritu said. “We have already received an offer from Paris and other museums are starting to approach us,” he said, adding that the experience would be relevant to audiences everywhere because migration “is a world problem. Anybody can relate to it. And no matter who we are, we were all immigrants once.”

• Visitors to Carne y Arena at the Fondazione Prada in Milan must book tickets in advance here