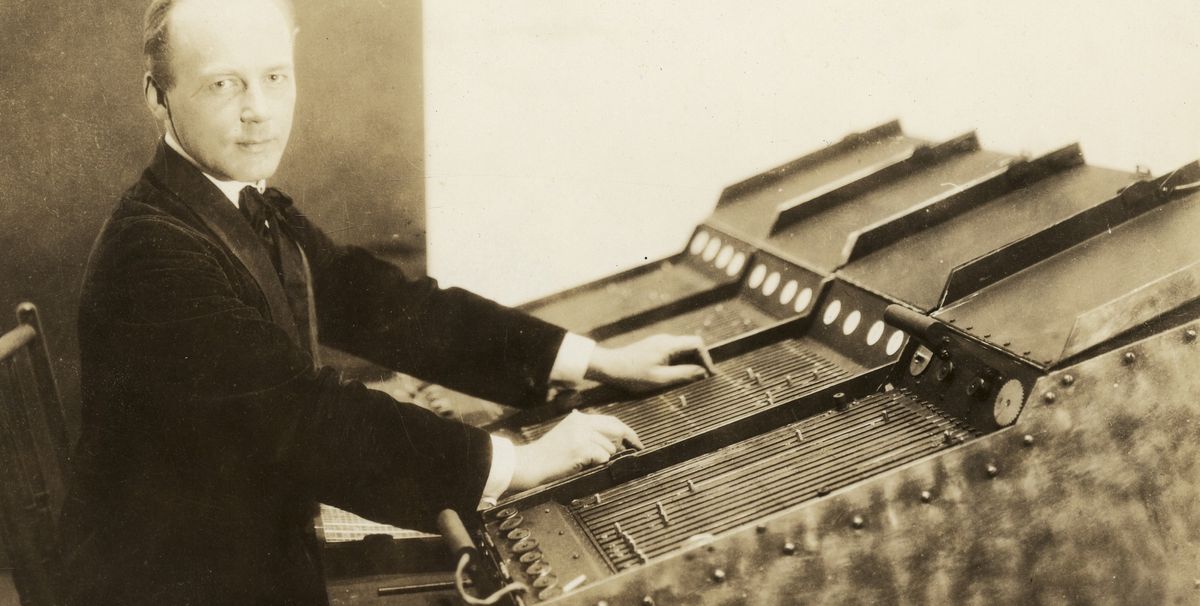

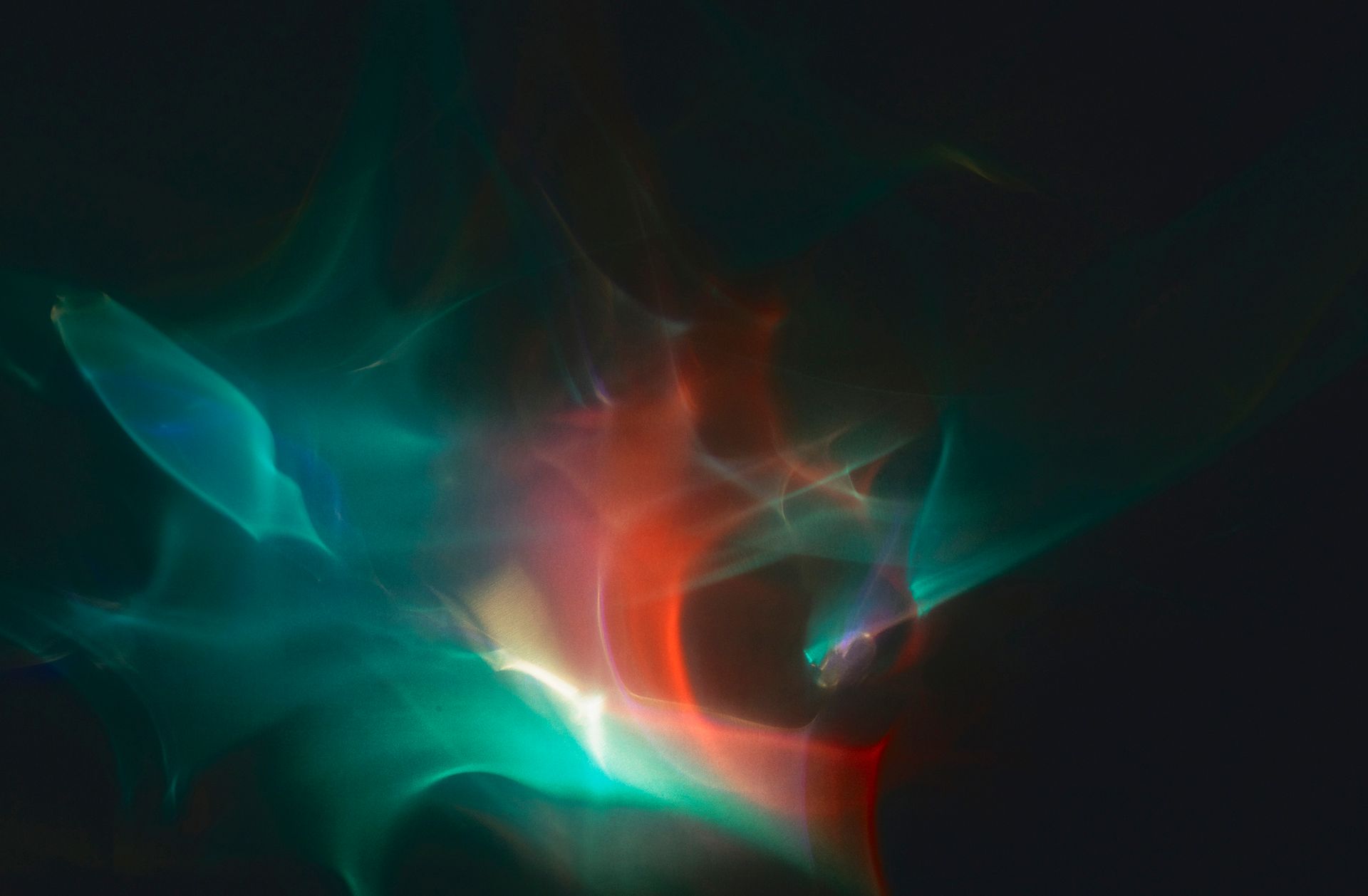

Nearly a decade ago, a Seattle-based collector visiting New Haven, Connecticut, asked to see three works from the 1920s and 1930s by the artist Thomas Wilfred in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery. The objects, two strangely resembling flatscreen televisions and one a lamp on a table, had remained deep in storage for decades. When the collector asked the accompanying curator and conservators to plug in and switch on the works, they were understandably hesitant. “One of us grabbed a fire extinguisher, just in case,” says Keely Orgeman, Yale’s assistant curator of American painting and sculpture, who has organised the gallery’s current survey of Wilfred’s light works. “But when we plugged the first one in, the ceiling was instantly filled with this multicoloured, swirling vortex.”

While Wilfred’s light pieces might not be as well known today, for a time they attracted thousands of viewers, in concert halls and theatres as well as in museums. The artist James Turrell remembers seeing one piece during a visit to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, that “stopped me in my tracks”, he writes in the foreword to the exhibition catalogue. Another room-sized installation, Lumia Suite, Op. 158 (1963-64) remained on permanent view at MoMA from the year it was completed until 1980,

when it was carefully dismantled and put into storage.

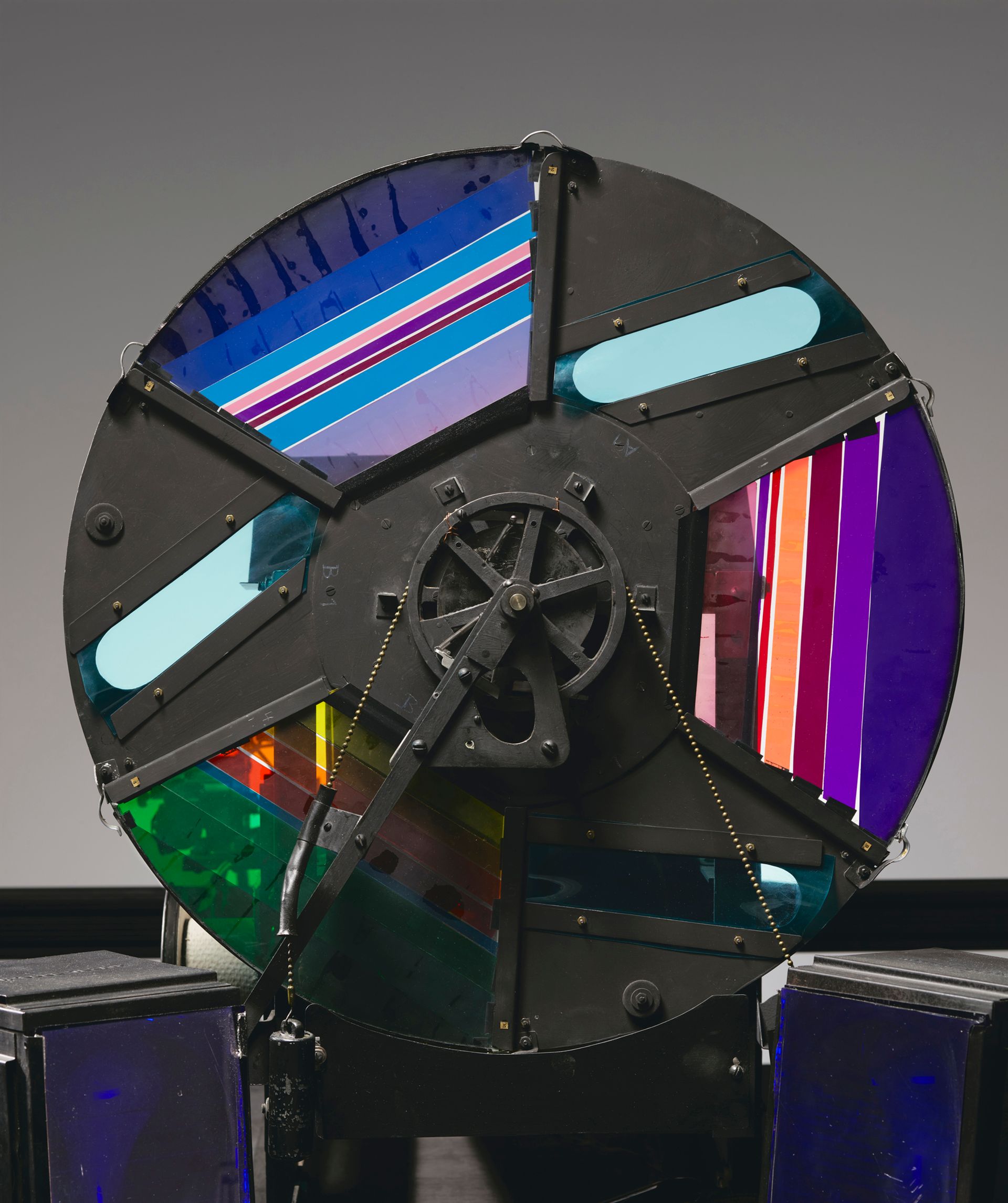

When Yale started planning its exhibition, the institution contacted MoMA about the works in its collection, including Lumia Suite, Op. 158. After some negotiations, the two museums agreed to collaborate on restoring the work at Yale’s state-of-the-art Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. “Boxes and crates of stuff arrived and we had to figure out what piece was what,” says Carol Snow, Yale’s deputy chief conservator and senior conservator of objects. “We started to develop this mantra of ‘some assembly required’.”

Fortunately, Wilfred had the foresight to write a detailed 50-page technical manual for the work, which clearly explained the specifications for every component, and how the fit together. “Wilfred was a genius for writing and leaving that,” Snow says.

As well as testing and updating the electrical wiring, creating a new screen and building a new black anodised aluminium mobile structure to house the projection elements, Snow had to track down a replacement for a key part: the 1,000-watt tungsten-filament GE light bulb at the heart of the work. No longer in production, the bulbs were originally manufactured for airport runways and lighthouses. “I wrote to the Coast Guard, I called airports, I found retired GE employees. I left no rock unturned,” Snow says. With no way of sourcing the original bulbs, Snow turned to the Portland, Oregon-based glass artist Dylan Kehde Roelofs, who hand-crafts light bulbs for his own sculptural work. He created a set of new bulbs for Lumia Suite that will replace the halogen ones found as a back-up for when the show travels to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC (6 October-7 January 2018).

• Lumia: Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, until 23 July