As institutions across the Netherlands continue to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of De Stijl, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague turns towards the movement’s greatest and most important artist: Piet Mondrian.

This month, the museum opens a show of all 300 works by the Dutch master in its collection—more than double the number included in the most recent career survey of his work, which was held there in 1994.

The current show, which will be organised chronologically, expands and corrects the narrative set out in that previous exhibition, says the museum’s director, Benno Tempel, especially for audiences who saw it at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, to where it travelled in 1995.

“In the American exhibition, almost none of the early works were included,” he says, referring to Mondrian’s representational paintings. That show presented “a very Modernist view of the artist; it was about the art and nothing else. Especially nowadays after Postmodernism, that’s a very strange way to look at art history, without the context of his time and his personal life.”

To bring that context into the show, curators have assembled photographs of Mondrian along with his letters and personal belongings—including his cherished gramophone collection. (Mondrian was a lifelong admirer of American jazz, and the painter Lee Krasner once recalled dancing with him at a club in New York in the mid-1940s.)

The Gemeentemuseum has a long association with the artist. Shortly after it opened in its current building in 1935, friends of Mondrian donated his landmark 1933 painting Lozenge Composition with Four Yellow Lines (see box). “It was one of the first really abstract paintings in the collection, so it could not be combined with anything else in the museum,” Tempel says. Eager curators found a simple solution by installing it in a staircase.

Many of the Mondrian works in the museum’s collection came to it in the 1950s and onwards, when the director, Louis Wijsenbeek, worked closely with the collector Salomon Slijper. Both men were Jews who survived the Second World War and “instead of looking backward, they looked forward”, Tempel says. “They wanted a style that could include everybody, no matter your background or religion,” he says—a mould that Mondrian fitted perfectly.

The show is accompanied by two new Dutch publications: a biography of Mondrian by Hans Janssen (published by Hollands Diep) and a book focusing on the pictures in the Gemeentemuseum (published by Waanders).

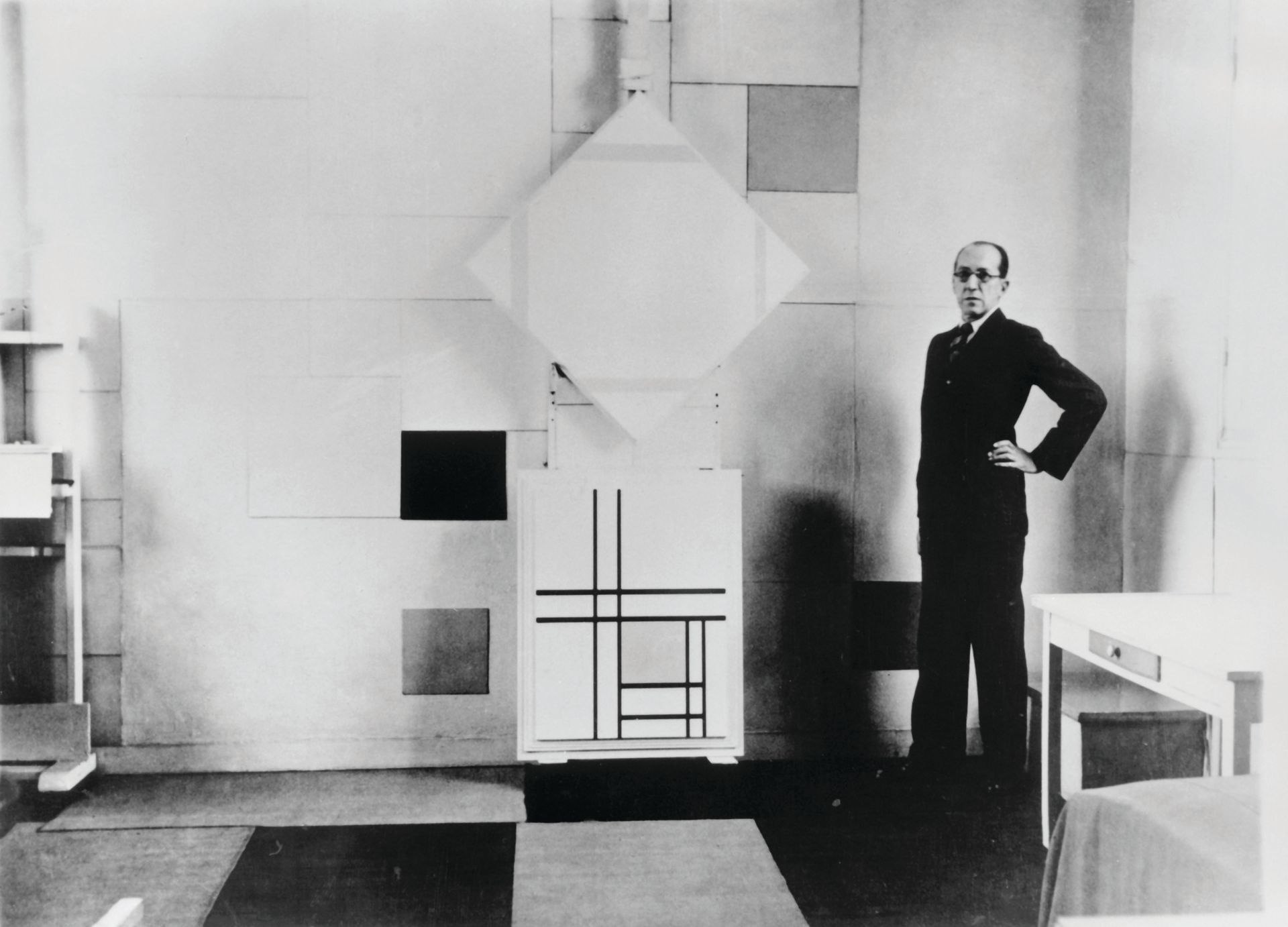

Piet Mondrian in his studio, 1933 photograph by Charles Karsten

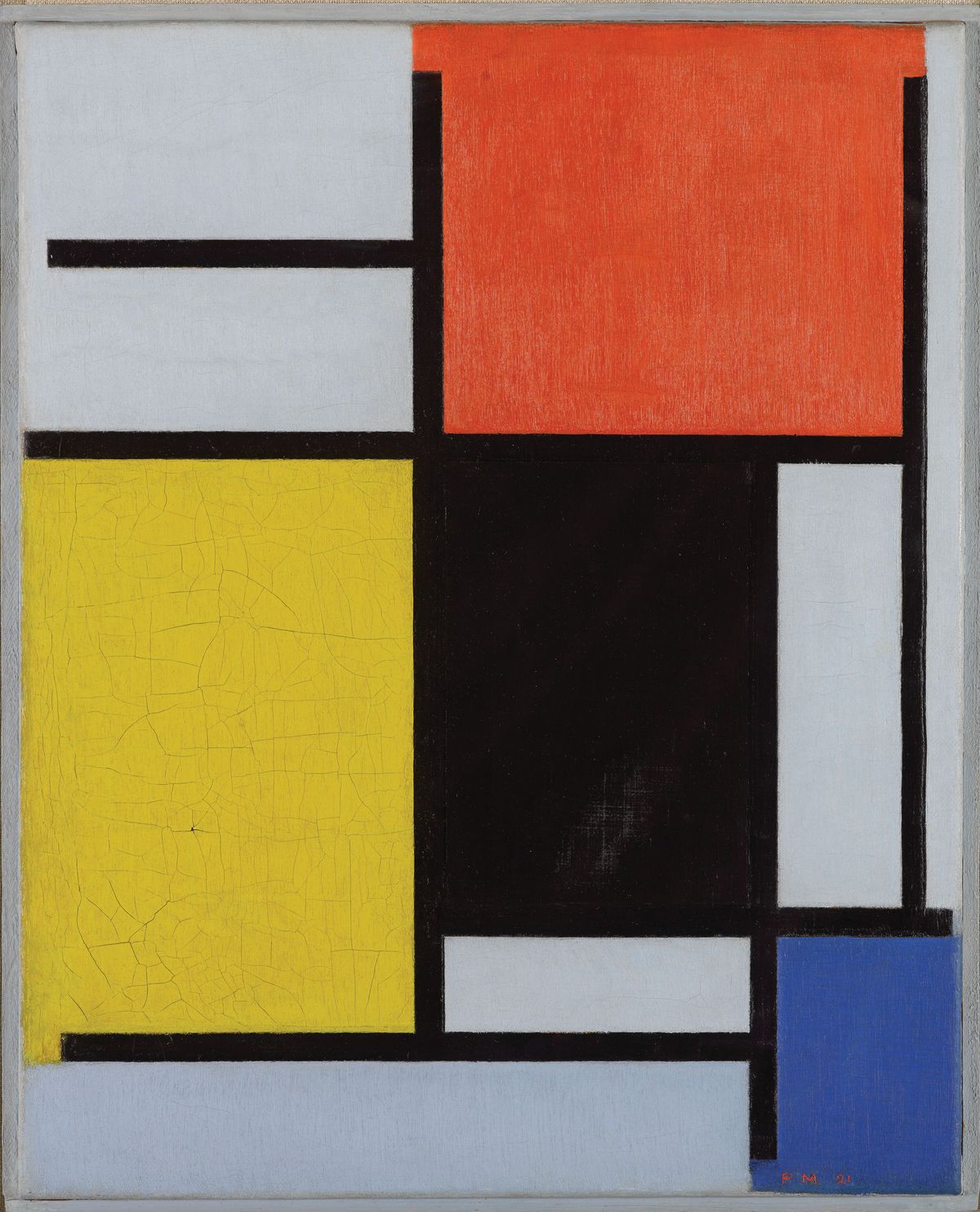

The Dutch architect Charles Karsten may not have realised it, but when he took this photograph of Piet Mondrian in the painter’s Paris studio in October 1933, he was documenting a radical change. Between 1920 and 1932, Mondrian had carefully built the style for which he is best known, with blocks of primary colours (and sometimes grey) kept in check by black vertical and horizontal lines. But after 12 years, be began to feel restricted. The painting pictured at top, Lozenge Composition with Four Yellow Lines (1933), was an early attempt to rid his paintings of black altogether. That idea flourished in his final, unfinished work, Victory Boogie Woogie (1942-44), which is a patchwork of red, yellow and blue. The other painting in the photograph, Composition with Double Lines (finished 1934), spoke to an altogether different and paradoxical idea. As Mondrian put it: “I am presently involved in new research into painting with double lines. Thus in a sense I do away with the black which I find less and less appealing.”

• The Discovery of Mondrian, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, 3 June-24 September

• For more on this story, see Dutch museum’s entire Mondrian collection gets a health check

• For a round-up of De Stijl, see De Stijl in the Netherlands: a round-up