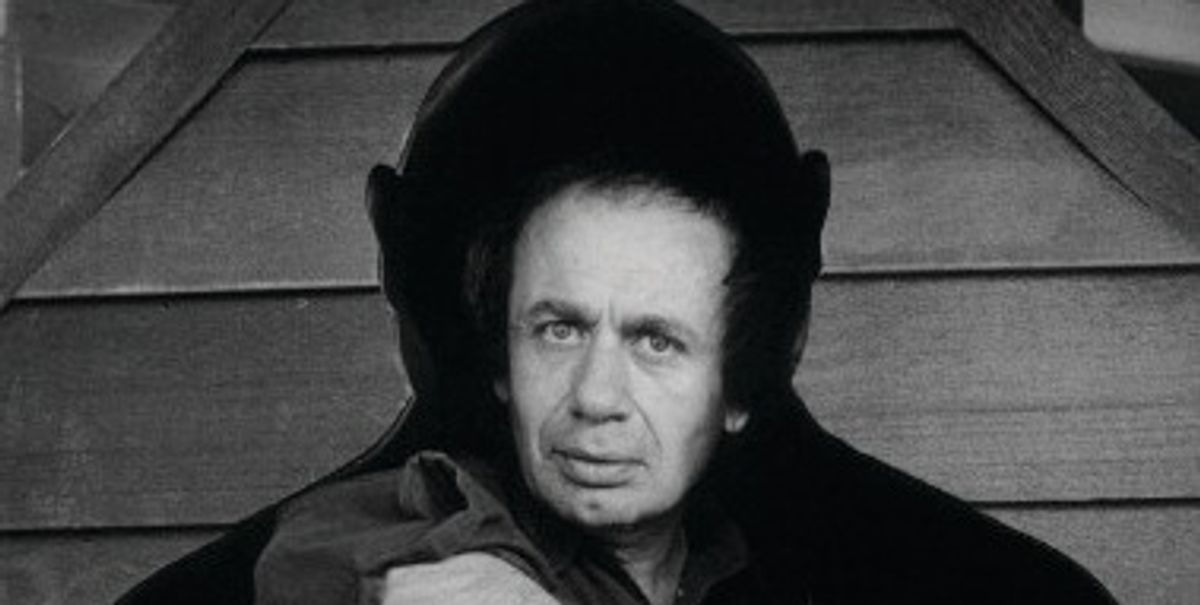

Poet, sculptor, performance artist and architect, and many other things, Vito Acconci died on 27 April, aged 77. Acconci was an artist who built an early reputation on acts that would make an audience uneasy. At the end of his life, in a career survey, he was recognised as the pioneer that he had been for 50 years. A man always clad in black, with a dour, weary face that made him look like the Rodney Dangerfield of the art world, Acconci was a prodigious speaker, but it was when he combined talk with action, at a time when performance art was a term few knew, that controversy came.

Architecture is about time rather than space, Acconci liked to say. He was also convinced that the future of architecture was mobility. Studio Acconci’s many projects, most of them modestly budgeted, included the exterior wall of the Storefront for Art and Architecture in Manhattan (with Steven Holl, 1992-93), and the floating Murinsel (2003), a “person-made island” in Graz, Austria.

“Your relationship to your body is determined by the times that you inhabit, and it’s either a comfortable one or an uncomfortable one,” said Bob Riley, a curator who acquired and exhibited Acconci’s work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “He understood that, and documented the uncomfortable aspects of his presence in the world, and he brought that into a working method with all materials—with handwriting, with photographs, with architecture, with video, with space-specific installation.”

Violate limits of acceptability The signature moment in Acconci’s early career is Seedbed (1972), a performance in which he sat under a floor at Sonnabend Gallery in New York with a microphone and masturbated during an eight-hour period while speaking of his fantasies about people who were sitting above. Comments about that work’s “seminal” influence have been a running joke in the art world ever since. “How often that could be done in the course of an eight-hour day is a little absurd, and points to the humour of the proposition,” said David Carbone, a New York artist. Critics also cited Acconci’s willingness to violate limits of acceptability, often offending or disgusting the public. His performances did both. Women, and his own body, were frequent targets. “He was male, and it was not heroic,” said Riley.

Acconci was one to deflate grandeur with an irreverent jab, even when it came to the monumental works of Richard Serra, whom he insisted on calling an architect. “I’d like it so much more if when you got inside a Torqued Ellipse there’d be a hot dog stand inside so that there’d be something for you to do,” he said in 2012, repeating a comment that he had made in many interviews.

Vito Hannibal Acconci was born in the Bronx in 1940, son of an Italian-born father and an Italian-American mother. His grandmother, who spoke no English, was named Crocifissa or Crucifix. In an interview conducted in 2008 for the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution, he spoke about his fascination with language from an early age. He also spoke of drawing pictures of his mother in the kitchen.

Acconci attended Catholic schools and college. “Probably the best decision I could have done because, maybe if I had gone to Yale, Amherst or Columbia, I might be a practising Catholic,” he said in 2008. He went on to study creative writing, wrote poetry, and published a literary magazine inspired by numbers used by Jaspers Johns in paintings.

He soon turned to performances where words and his body were each a medium, moving through photography, video, sculpture, design and eventually the practice of architecture. “He once told me, ‘When I did Seedbed, I wanted to be part of the building,’” recalls Conrad Skinner, a Santa Fe architect, who introduced Acconci to local colleagues. “Back in 1972 he was already talking about his engagement with physical space,” he says. “Vito wanted to take what he had done in his performances, and expand that into conditions where people who were interacting with his buildings would have the same kind of experience, so that they would somehow get physically involved in the building.”

Limitless self According to the MoMA PS1 director Klaus Biesenbach, who organised a retrospective of Acconci’s early work there last year, “he very radically explored the boundaries of his mind, of his body, and his boundaries as an artist. Then he finally decided to become an architect, both to be truly public and to interact with the public sphere.”

More than 40 years ago, according to Biesenbach, Acconci was exploring his own image. “His photographs documented so many early performances and interventions, and many early actions were videotaped and filmed,” he says. “Many of the early works looked like selfies or YouTube channels of exploring.”

Yet Acconci wouldn’t be limited by much, and certainly not in the range of his influence. “For all the conceptual ideas of performance art, Acconci was interested in the humanness of the human body”, says Carbone. “In an age of abstraction, Acconci brought to centre stage the importance of the human figure. Even when he was biting himself to make signs on his flesh, it was about the experience of being alive in your body, and exploring that.”

• Vito Acconci, born 24 January 1940, died 27 April 2017