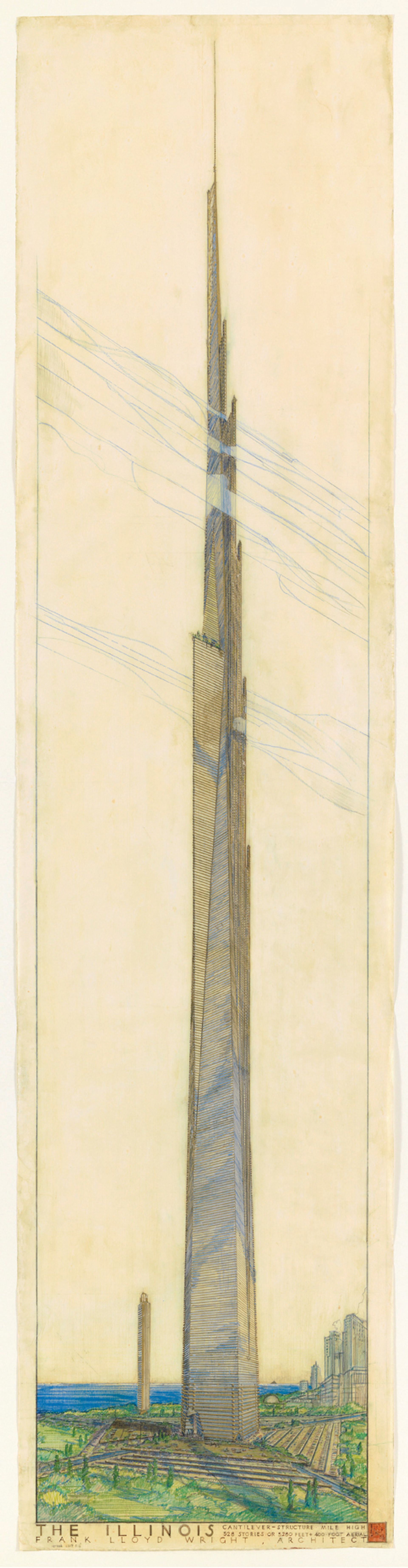

On 16 October 1956, Frank Lloyd Wright hosted a press conference at Chicago’s 1,700-room Hotel Sherman. Perhaps the US’s most famous architect needed a truly big venue to unveil the Illinois, a proposal for a mile-high skyscraper boasting 528 floors, served by 56 atomic-powered elevators, housing 130,000 tenants and equipped with a garage for 15,000 cars and twin helipads for 100 helicopters.

Knowing how to seduce the press, Wright’s 9ft perspective drawing of the 5,280ft tower—dramatic enough in its own right—was enlarged, photographically, to 22ft. This was not just thinking big, but radically, too. Strangely, or so it must have seemed, the Illinois was part and parcel of Wright’s belief that the modern city was a monstrous, sprawling creation that needed to be kept in check. Ideally, a city the size of Chicago could be housed in just a very few vertiginous skyscrapers surrounded not by streets but by fecund parkland. Wright’s religion was nature with a capital “N”. The Illinois was a way of protecting and encouraging nature by condensing and containing the modern city.

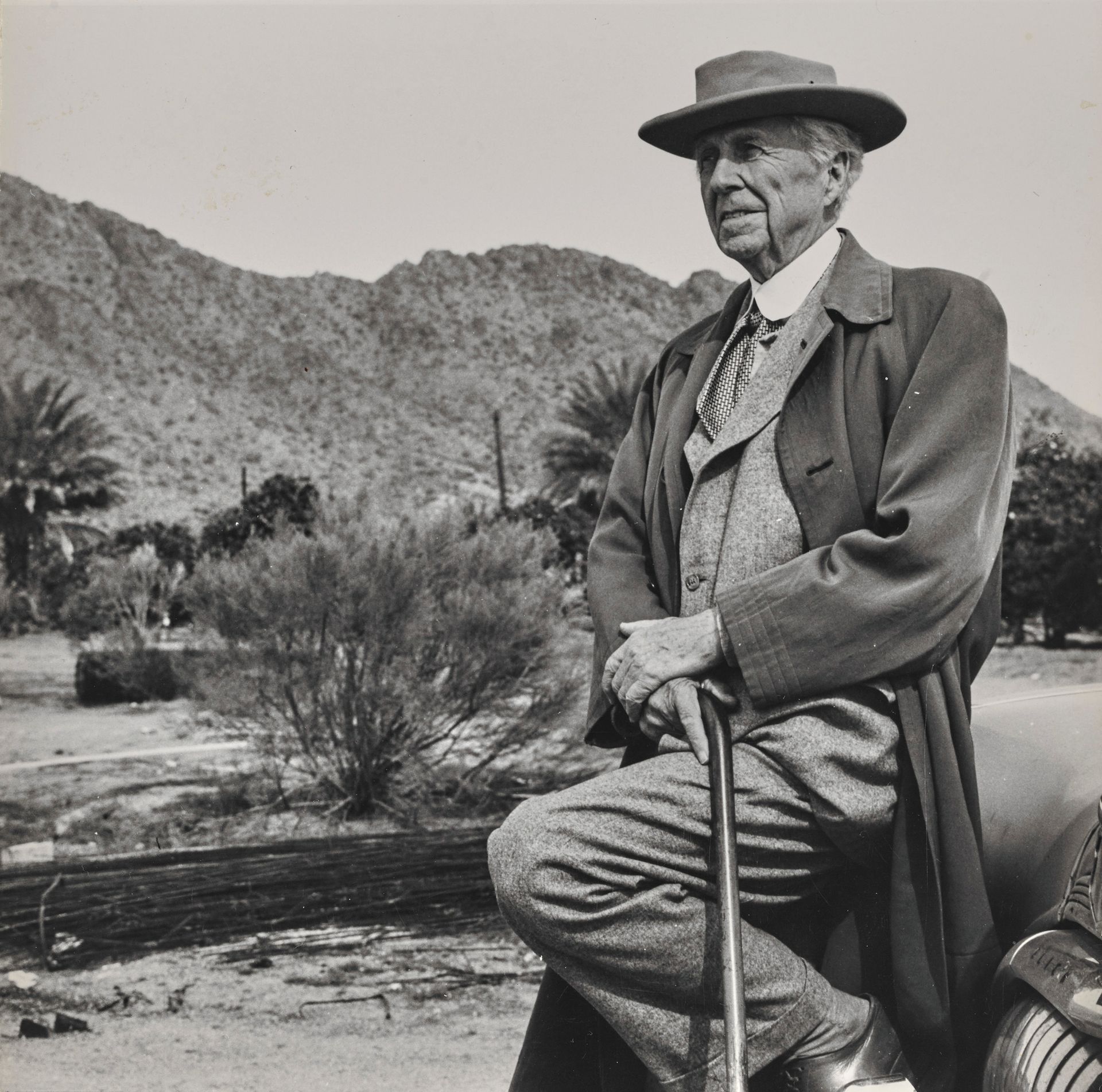

The press lapped up the story. The 88-year old architect was good copy, as he had been for much of the past 70 years. Controversial, outspoken, witty and inspired, Wright thought big and acted on a very large stage indeed. His life had been the stuff of high drama and headline-stealing tragedy. Homes (two) burned down. Mistress and her children murdered by a mad axeman. High-profile divorces. And, lest any US newspaper journalist forget, a succession of brilliant and innovative buildings and design proposals almost from the day he set up shop under his own name in 1893. Frank Lloyd Wright contained multitudes.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, the archives he left for posterity are on a multitudinous scale. In 2012, these were transferred from Wright’s former Taliesin studios in Wisconsin and Arizona to Columbia University and New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Since then, curators have been unpacking around 55,000 drawings, 300,000 sheets of correspondence, 285 films and 2,700 manuscripts.

To celebrate Wright’s 150th anniversary, MoMA is putting around 450 works from the archives on display in a new exhibition, Unpacking the Archive. Alongside these, it has published an ambitious catalogue featuring wide-ranging essays attempting to interpret this architectural wealth. It does need some interpretation, for over a 72-year career, Wright’s style of design and drawing evolved, like those of long-lived painters, through a number of “periods”. What these have in common is compelling and often quite brilliant draughtsmanship, displaying the successive influences of the Arts and Crafts movement, Japanese printmaking, the Viennese Secession, Art Deco, European Modernism (not that Wright would ever admit this, especially given his influence on the latter), automotive styling—Wright owned 85 cars in his lifetime—and even, perhaps, Hollywood.

Wright would have made a particularly fine art director and set designer. His own dramatic life was, in part, the inspiration for Ayn Rand’s best-selling novel, The Fountainhead (1943), given a melodramatic Hollywood treatment in 1949 with Gary Cooper in the lead role. Although the main character owed as much to Le Corbusier in his outlook and ideals as he did to Wright, there was no question that the picturesque Wisconsin architect was anything other than a star. And Wright knew it. Asked for his occupation in a court of law, he had replied, “The world’s greatest architect”. When his third wife, the Montenegrin ballet dancer Olgivanna Lazović, remonstrated with him, he replied, “I had no choice, Olgivanna. I was under oath.”

Talent scout In the late 1950s, as the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum rose on Fifth Avenue, and as his studios continued to produce unprecedented proposals for future buildings, Wright appeared on television several times, proving to be engaging, amusing, memorable and profound, and certainly so in the live interviews he gave in September 1957 for The Mike Wallace Interview on religion, war, mercy killing, art, critics, America’s youth, sex, morality, politics, nature, death and his mile-high skyscraper.

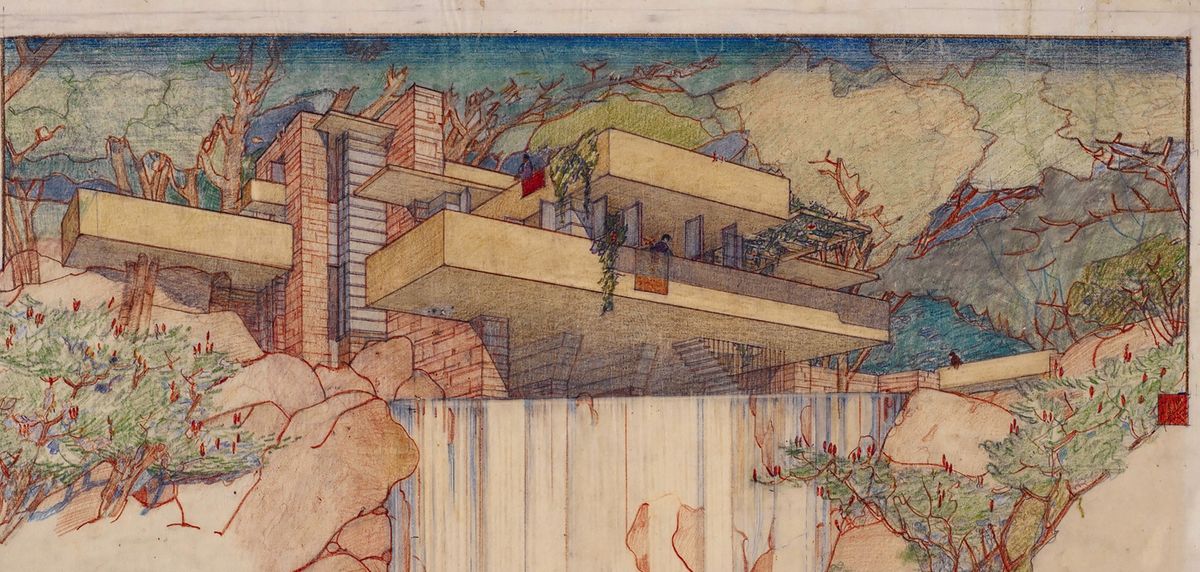

Driven by big ideas and a desire to reach nationwide audiences, Wright mastered any number of presentation techniques, from coloured pencil drawings to books, magazines, exhibitions, monographs, films, radio and television. He even appeared on the popular TV quiz show, What’s My Line? He also knew—the MoMA exhibition is very good on this—how to attract talented young assistants, some straight from high school, who, quite simply, drew beautifully. In fact, the MoMA exhibition reveals many of the set-piece Wright drawings to be the work of assistants, notably Jack Howe, known as “the pencil in FLW’s hand”, who, joining the studio in 1932 aged 19, was its chief draughtsman from 1937 when Fallingwater in Pennsylvania—one of the most renowned of all US buildings—was under construction.

Wright’s very first assistant, taken on in 1895, was Marion Mahony, one of the first women to receive a degree in architecture. Her contribution to Wright’s work was considerable, her drawings and watercolours superb. In 1910, the Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth produced a two-volume folio of 100 line-drawing lithographs of plans and perspectives of Wright’s buildings to date. Drawn in a consistent house-style, more than half were by Mahony. Not only had she set the tone and style of the portfolio drawings, but she had also—in a trice, and in Wright’s name—won the minds and pens of key members of the first generation of European Modern architects.

A copy of Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright was despatched to the Berlin studio of Peter Behrens. Work there is said to have stopped for a day as the German architect’s apprentices pored over the drawings. These happened to be Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. Other copies made their way into the hands of the young Austrian architects Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, both of whom were to emigrate to the US and work for Wright before doing their special bit to create a recognisable modern Californian architecture. Drawings at the end of the First World War of Wright’s proposals for American System-Built Homes were made by Schindler together with the young Czech architect Antonin Raymond who, in the wake of the Second World War, was one of the fathers of modern Japanese architecture.

Wright read Whitman poems to apprentices and assistants at Taliesin West

Wright’s connection to Japan—he had a lifelong love of Japanese prints, which he collected—was always strong. The MoMA exhibition shows a rare photographic portfolio of Wright’s Imperial Hotel (1913-23), a complex building damaged by the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923 and demolished in 1968. Designed, said Wright, “as a system of gardens and sunken gardens and terraced gardens, of balconies that are gardens and loggias that are also gardens and roofs that are gardens”, it served as a bridge between his early and middle periods as an artist-architect and as a link between Eastern and Western design.

Wright spent much time in Tokyo, drawing on Japanese rice paper and rolls of tracing paper that, back in the US, he continued to order for his Taliesin studios. In the 1920s, his assistants included the Japanese husband-and-wife architects Kameki and Nobuko Tsuchiura who had worked on the Imperial Hotel. Nobuko was the first Japanese woman architect.

Later assistants and apprentices, working at Wright’s idealistic Taliesin West studio—part “back-to-the-land” farm, part architecture studio—included Elizabeth “Betty” Bauer, the head of MoMA’s architecture and design department during the Second World War. “Betty is in the trenches in blue overalls,” wrote Wright to a friend, “and all outdoors sweating like a colt. Much of the New Yorker has been shed with the perspiration.”

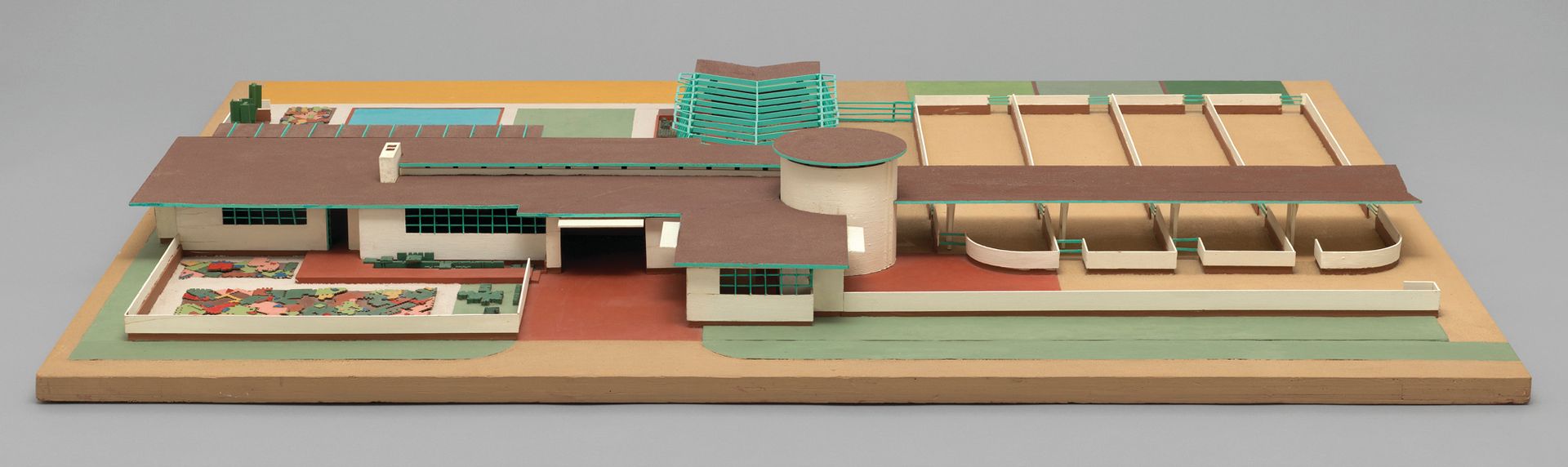

Romantic ruralism The MoMA show places significant emphasis on Wright’s love of nature and belief that life is best lived well beyond the city. In 1932, on the back of Roosevelt’s New Deal and in co-operation with Walter Davidson, an engineer, accountant and management consultant to the US food industry, Wright drew up plans for “Little Farm Units”: one- to five-acre, self-reliant smallholdings unifying farms and co-operative roadside markets. Models and drawings of these remain compelling. Imagine living this way—Wright’s way—rather than in the rural commuter dormitories of the 21st century that have little or no connection to either nature or the land they smother.

The Little Farm Units scheme came to nothing, although models and drawings take us to the heart of Wright’s romantic ruralism. His abiding love of nature and his preoccupation with individualism were rooted in the 19th-century writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. All three—essayists and poet—sung the praises of a self-reliant, independent and individualistic American rural way of life. Wright read Whitman poems from his 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass (1855) to apprentices and assistants at Taliesin West. And, evidently, he lived his life according to this sentiment expressed towards the end of Thoreau’s Walden; or, Life in the Woods (1854): “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”

Wright’s was a massive and very particular presence, yet he did not walk alone. In the exhibition, this is well expressed by the model and drawings of Broadacre City—“architecture + acreage” according to Wright’s equation—a project begun in the early 1930s proposing a kind of low-density garden city, a riposte to New York and Chicago shaped by a host of young architects. The presentation of this unrealised suburban utopia, even if you disagree with the anti-city philosophy underpinning it, remains as exciting as it was when first exhibited in the Rockefeller Center, New York, in April 1935.

Broadacre City morphed into the Living City project of 1958, complete with futuristic cars and science-fiction style flying machines to bring it up to date for new and younger audiences. It was a companion piece to Wright’s mile-high skyscraper. Wright might have wanted Americans to lead a self-sufficient rural life but—boy—did he know how to woo urban audiences through these eye-catching projects and through every media channel available.

What Unpacking the Archive shows us is that, aside from being a highly original architect with the ability to pick talented assistants, Wright, whatever you make of his ideas, his projects and his ego, was a brilliant communicator. He has been the subject of more exhibitions than any other architect. His work featured in MoMA’s very first architectural show—Modern Architecture: International Exhibition (1932), curated by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson—and here he is again, 85 years on, as alive and as thought-provoking as he was when, in downtown Chicago and aged 88, he revealed that unearthly skyscraper.

• Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 12 June-1 October, moma.org