The first ever sale of African art by Sotheby’s London on 16 May reflected both the current interest in the art and the immaturity of this market, and posed the question, what is African art anyway.

The ultra-chic Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris is showing (until 28 August) a selection of the biggest collection of African art in the world, put together by the Frenchman, Jean Pigozzi. This is proof of interest in the subject, even though the show’s title—Art/Africa: le nouvel atelier (the new studio)—suggests an unawareness that African art is not a new discovery, having featured prominently in Venice Biennales and Documentas over the past decade, while the specialist art fair 1:54 has been bringing African artists to London, and also New York, for the past four years.

On the other hand, the auction achieved only £2.3m (hammer prices), with 32 of the 115 lots (28%) unsold, even at very low estimates, revealing that there may simply not have been enough people bidding.

In the case of such a large and disparate territory as “Africa”, about which many Westerners still know very little, the comfort of institutional backing is necessary to persuade them to risk their money. This institutional support is almost non-existent in sub-Saharan Africa but also in major Western museums such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Tate, the Centre Pompidou, all still without departments of African art. Nor is there the promise of a boom economy: the commodities-driven 5% p.a. growth rate of 2010-14 is over and the increase in Africa’s GDP slowed to 1.3% last year.

Thus, of the two works by Romuald Hazoume, who riffs on the theme of African masks using industrial rubbish, one sold for £7,000 and the other was bought in, despite the fact that masks by him are being used to publicise the Fondation Vuitton exhibition and he has been widely shown in Western exhibitions.

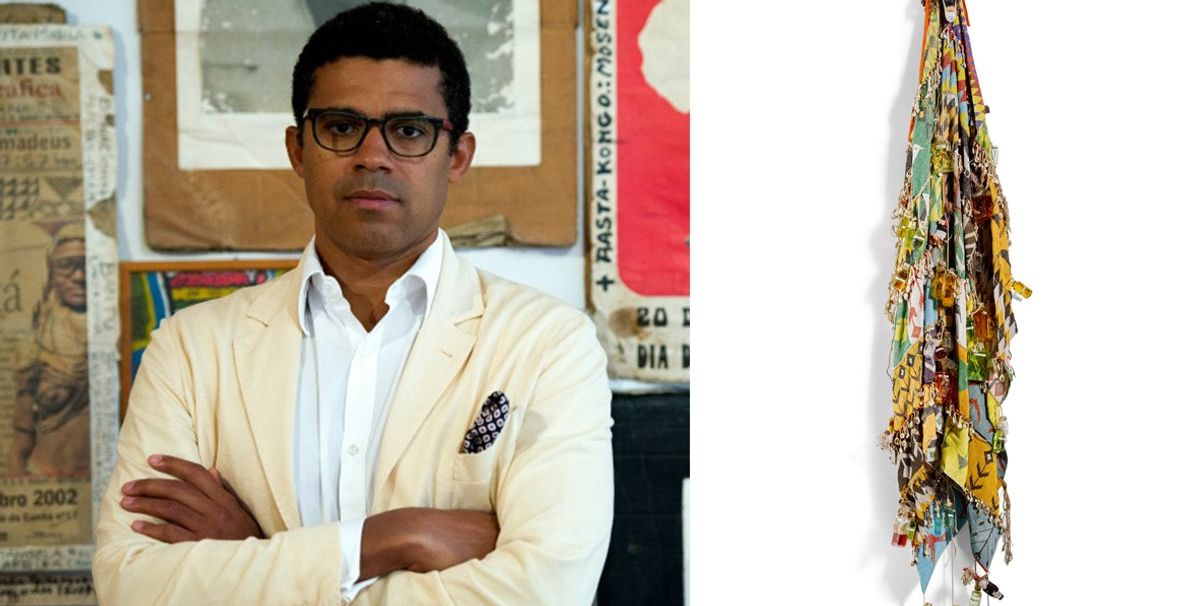

The sale total would have been even more modest without the £600,000 paid for a large, decorative, bottle-top hanging by Nigeria-based El Anatsui, a darling of Western museums, and £340,000 for a 1942 still life of sun-flowers by Irma Stern, a prominent but unexceptional (by international criteria) South African artist. These high prices can be explained by the fact that both artists have established markets of their own, the former in the West, the latter in South Africa.

Two other high prices were for artists who both have good sales records in international contemporary art sales, so their market identity is not African at all: Yinka Shonibare’s red car with a figure dressed in his characteristic African, printed textiles sold for £180,000, and Franco-Algerian Kader Attia’s sculpture made from a scooter shell fetched £19,000.

“African” is a broad, probably too broad, category, and the sale included a group of South African, genteel, colonial landscapes by Jacob Pierneef that looked very out of place in this context and did not find buyers. Such works need their own dedicated sale.

William Kentridge, on the other hand, also South African, but firmly in the category of international contemporary art, sold predictably well, with the prominent Angolan collector Sindika Dokolo buying his six linocuts of birds for £17,000. Dokolo also acquired a wall sculpture by the South African Willem Boshoff for £7000; a woven textile and rubber work about sexual identity by Nicholas Hlobo, a South African with a strong exhibition record in Western museums, for £48,000; an imposing textile and scent-bottle work called Cache-Sexe by the Cameroonian Pascale Marthine Tayou, whose gallery is the powerful Galleria Continua, and two works by Angolans: a mixed media wall sculpture by António Ole for £16,000 and a painted diptych by Francisco Vidal for £10,000.

There was good work to be had at this sale at very affordable prices and there is no doubt that the entry of a major auction house into the market process would help the African art scene develop, just as the 2006 Christie’s auction of Middle Eastern art in Dubai persuaded locals that art was something to take more seriously. The way forward might be a sale of a more focused body of sub-Saharan contemporary work, with more introduction of the artists and their origins.