Christine Macel, the director of the 57th Venice Biennale and the chief curator of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, promised an exhibition with “art and artists at its centre”, and an exploration of the way that artists, in her words, “wish to reinvent the world”. Her exhibition, called Viva Arte Viva, welcomed invited guests yesterday; it will open to the public on 13 May and runs until 26 November.

What Macel has given us is a thoughtful, logically-argued show, if one that tends towards the cerebral and at times is a little cold. While she has been criticised for failing to significantly increase the number of women and non-white artists above Biennale norms, she has clearly been making an effort to present less well-known artists, both critically and commercially. Of the 120 in the two-site exhibition (in the Giardini and Arsenale), around 70% have never been seen in Venice before, with an emphasis on mid-career, older and some dead artists, over hot young things.

The exhibition starts in the Giardini, in the central pavilion, with two of Macel’s nine main sections, or “trans-pavilions”. This is a journey that begins in the artist’s studio and ends in the Arsenale in an exploration of art’s power to transcend everyday concerns and even touch the sublime.

The first trans-pavilion is the Pavilion of Artists and Books which looks at the different ways artists find inspiration and make their work. Among the highlights is Olafur Eliasson’s Green Light project, created in collaboration with Vienna's Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, bringing together refugees and visitors to collaborate to make lamps that the Danish-Icelandic artist has designed (for sale at €250 to support the project) and share stories and experiences. This is placed at the heart of the show.

The work takes a darker turn in the Pavilion of Joys and Fears which brings together art that deals with the body and the strong emotions that arise from it. Perhaps most disturbing is the work of the late Hungarian performance artist and photographer Tibor Hajas. Atmospheric photos have been manipulated so that the naked artist’s body appears to disintegrate.

Meanwhile, in the medieval ship-building yard, the Arsenale, the majority of the work and artists chosen by Macel can be found, along with the remaining seven trans-pavilions. The journey could be daunting—from the Pavilion of the Common to Time and Infinity (in two parts)—but the curator has paced the many large-scale works skilfully. Theoretical overload, longueurs and other curatorial pitfalls are avoided.

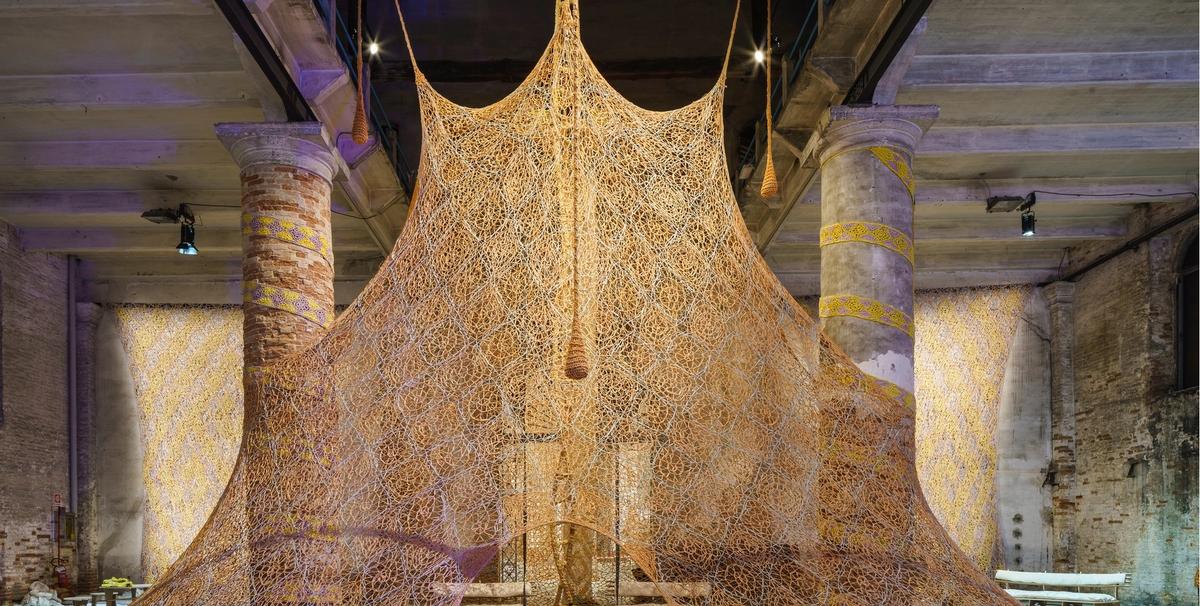

The US artist Charles Atlas’s large-screen video work The Tyranny of Consciousness (2017), narrated by the drag queen Lady Bunny, conveys her dismay at American politics to a disco beat. The artist as shaman section revolves around Ernesto Neto’s A Sacred Place (2017), a tent-shaped structure suspended from the roof in which members of the Amazonian tribe, Huni Kuh, are in residence.

The Vietnamese-born, Paris-based Thu Van Tran’s installation The Red Rubber (2017) and accompanying works, including film, wax casts of tree trunks and large-scale abstracts that refer to the exploitation of natural resources impresses nearby. If such works sounds worthy, the reality is visually seductive and formally impressive, best summed up by young, Swiss-born, Berlin-based Julian Charrière’s Future Fossil Spaces (2017). Hexagonal towers of stone incorporate lithium, or “white petroleum” which complement the brick columns of the Corderie building. As with many of the works, the political remains a subtext while surfaces seduce.

One of the most successful site-specific installations is the US-born, Paris-based artist Sheila Hicks’s Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands (2016-17), which forms a technicolour cliff of great fabric balls. Nearby hang paintings by another veteran artist, this time Italian. Giorgio Griffa’s riff on Agnes Martin’s subtle colours is among many surprises Macel has in store. Most of the 120 artists she has annointed in Viva Arte Viva are perhaps better known to other artists. Until now.