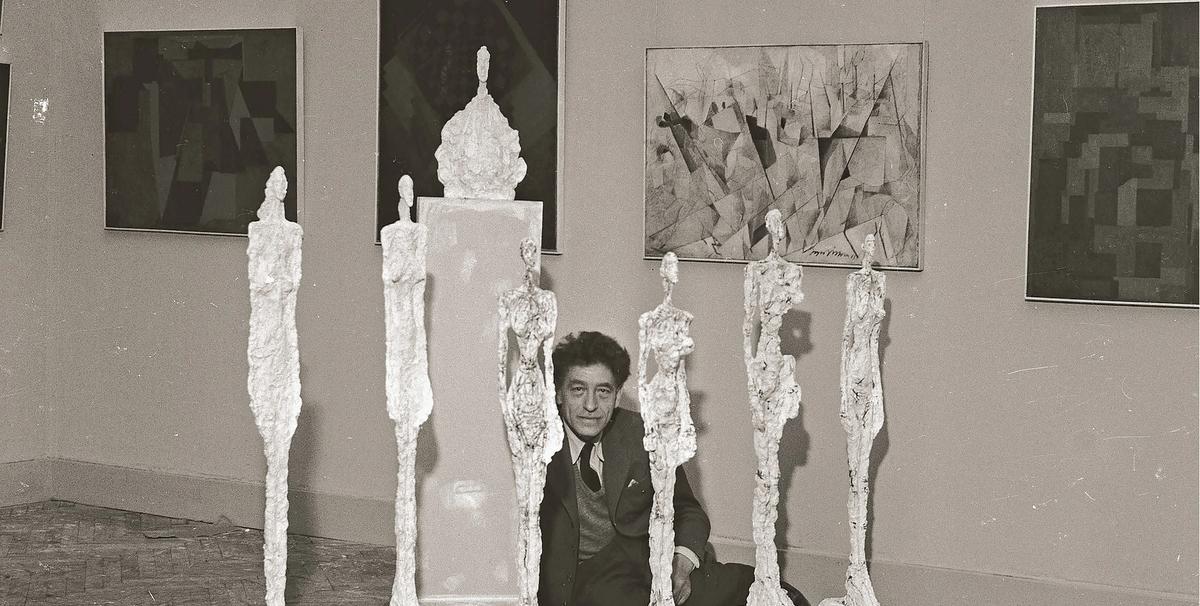

Bronze editions of Alberto Giacometti’s Women of Venice can be found in major museums across the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. But what happened to the six plaster originals, first shown in the French pavilion at the 1956 Venice Biennale, that were used to cast these bronzes?

In pieces and too fragile to go on display, they sat in the storeroom of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti in Paris for decades. Tomorrow (10 May), thanks to the efforts of a team of conservators, the restored pieces will go on display together for the first time in more than 60 years at London’s Tate Modern. They form the centrepiece of the museum’s first major UK retrospective of the Swiss artist in 20 years.

The painstaking restoration of the Women of Venice plasters took around a year and involved a team of conservators, including specialists in plaster and armature, says the foundation’s director and co-curator of the Tate show, Catherine Grenier. The team faced two main challenges. The first involved using a laser to remove the brownish-orange shellac applied to reinforce the plasters’ surface before the casting process. The goal was to recover both the original paint, as Giacometti painted some of the plaster figures, and tool marks that had been lost under the shellac. Lena Fritsch, Tate Modern associate curator and the co-curator of the show, says the dark-brown paint gives them an “archaic effect” unlike some of his earlier, brightly coloured painted plasters such as Head of a Woman [Flora Mayo] from 1926.

Reassembling the sculptures, which had to be cut into pieces to be cast, and stabilising them so they could stand safely on their own was the second obstacle and, in Grenier’s eyes, possibly the more challenging of the two, especially as any intervention needs to be reversible in accordance with current thinking in the conservation field. Grenier stresses that the sculptures, although restored, remain fragile and so will not be shown often at their premises in Paris. Other plaster works treated ahead of the show include another statue of a standing female figure, Woman Leoni (1947-58), and The Nose (around 1947-49).

Women of Venice, modelled after the artist’s wife, Annette, represent the culmination of Giacometti’s search for the adequate representation of the female form, says Fritsch. He made ten plaster figures in total (only nine were cast in bronze): six were shown in Venice and three were exhibited in his solo show at the Kunsthalle in Bern, which coincided with the Biennale. The Tate show features eight of these plaster works.

They are being displayed near a series of sketches Giacometti made of Egyptian funerary sculpture—a major inspiration for his Women of Venice series. “You can see the influence in the figures’ stance and large feet,” Fritsch says. Grenier adds: “As usual, he took inspiration from both the modern and the ancient, namely from the model, his wife Annette, and from ancient Egyptian statuary. He was mixing the real–the portrait–with the antique– Egyptian figures.” Showing the diversity of Giacometti’s influences—antiquities, Surrealism, Cubism, Post-Cubism—is one of the key objectives of the show. “He was a real innovator who experimented with a range of styles and looked at different art historical sources and materials,” Fritsch says.

Another aim is to stress the materiality of his practice. “People tend to associate Giacometti with his bronzes, particularly here in the UK. We want to show his interest in many different materials and textures,” Fritsch says, adding that the 250-piece exhibition includes bronzes, plaster works and paintings. It also features a selection of drawings—many of which have not been exhibited before—on loan from the foundation’s sizeable collection of works on paper by the artist. The foundation is the largest lender to the exhibition.

“We hope the exhibition will help to reassert Giacometti’s place along with big names like Matisse, Picasso and Degas as one of the great painter-sculptors of the 20th century,” Fritsch says.

• Alberto Giacometti, Tate Modern, 10 May-10 September