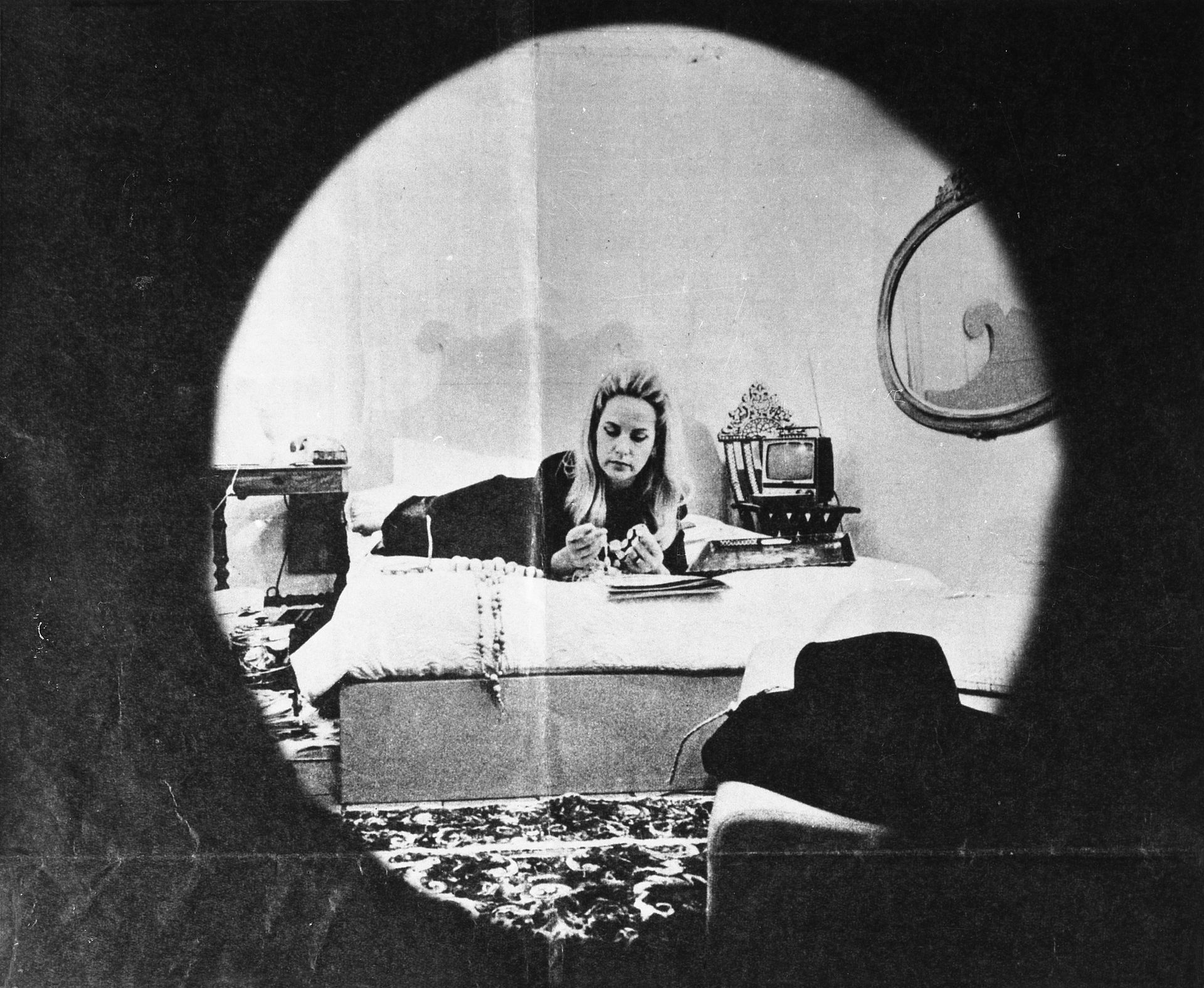

From afar, there was not much to see. On 6 May 1968, Galleria La Tartaruga in Rome looked closed. The door had been sealed off and there was no way in. Yet a sign reading “The optical spy by Giosetta Fioroni, or my bedroom action by Giuliana Calandra” implied that something was going on. Visitors who got close enough could see a peephole cut into the wall revealing a young woman in a bedroom sitting in bed, reading a book, manicuring her nails.

The performance—arranged by Fioroni, with Calandra playing the woman—was the first in a series of exhibitions at La Tartaruga titled Teatro delle Mostre (theatre of exhibitions). On most days for the rest of May, a new artist installed or performed a new work, with a new poster going up each day. “The idea was that it wasn’t announced, so to know what there was to see, you would go to the opening each afternoon,” says Cecilia Alemani, the director of the High Line park’s public art programme and curator of Frieze Projects. At the New York fair this week, Alemani has organised a four-day event with four artists (Fioroni, Ryan McNamara, Adam Pendleton and the estate of Fabio Mauri) that recreates and responds to Teatro delle Mostre.

Living sculptures For years, La Tartaruga’s founder, Plinio de Martiis, had encouraged artists to experiment with performance. At the opening of Piero Manzoni’s solo show at the gallery in February 1961, the artist “signed the bodies of some models and visitors so that they took on, thanks to his signature, the [status of] a work of art, or rather sculture viventi—living sculptures,” says the art historian Ilaria Bernardi, whose 2014 book Teatro delle Mostre chronicles the exhibition’s history.

A few years later, Paolo Icaro installed a prison-like sculpture that visitors were invited to enter. At the opening, the sculptor Pino Pascali “dangled from its bars while pretending to be a large monkey in a cage”, Bernardi says. But perhaps the most famous performance at the gallery was overseen by Andy Warhol. In February 1968, he had actors dress as cowboys and Indians dance together in a room full of prints and paintings that depicted a dead Che Guevara, the Marxist revolutionary killed the previous October. Warhol filmed the event.

In a sense, Bernardi says, these shows were Teatro delle Mostre forerunners “because they were equally ephemeral, site-specific, and required the participation of visitors”.

When de Martiis opened Galleria La Tartaruga (Turtle Gallery) in 1954, there was little sign of a radical programme—the first show was of lithographs by Honoré Daumier. But de Martiis had catholic interests, performance in particular. He was fascinated by the Italian Futurist Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s theatrical work, which inspired him to found the Teatro dell’ Arlecchino just after the Second World War. Its cabaret performances drew artists like Giorgio de Chirico and writers like Alberto Moravia.

“He was very influenced by new experimental tendencies that were popular in the 1960s,” Alemani says, citing the Polish director and theorist Jerzy Grotowski, who coined the term “poor theatre” in 1968 for productions stripped of elaborate costumes and extravagant sets. Grotowski and de Martiis aimed “to destroy the barrier between audiences and actors”, she says.

Some events during Teatro delle Mostre complicated that aim. For example, instead of collapsing the ‘fourth wall’, Fioroni’s work made it literally solid. Calandra knew she was being watched, but acted without interference. The artist Cesare Tacchini’s show a few days later, in which he “cancelled” himself, was equally distancing: he sat in a room behind a pane of glass and painted it white till he was no longer visible.

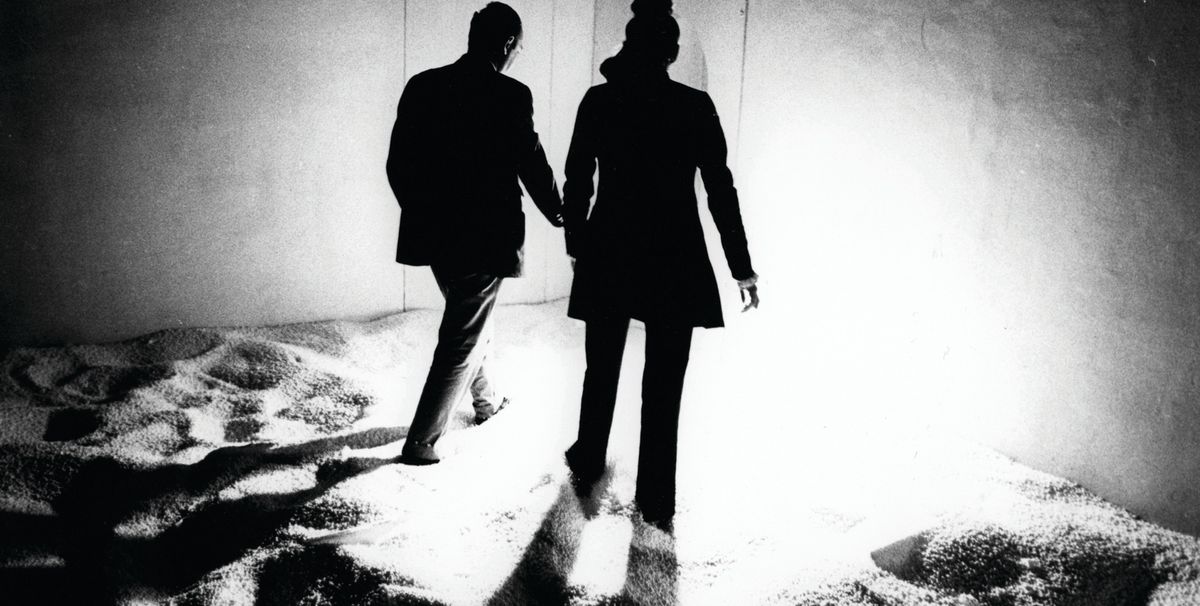

Yet other works made it practically impossible to avoid fellow viewers. With his Luna (1968), in which he made the gallery resemble the moon, Fabio Mauri encouraged visitors to sit and relax on layers of polystyrene; some stayed for hours. Another artist, Franco Angeli, lowered the gallery’s ceiling for his show to create a claustrophobic environment, with visitors clustering together and forced to interact.

But in each case, the object lost its privileged status. Works of art became experiences, rather than just paintings or sculptures. “It was a break with the passive white space of the museum,” Alemani says. Or, as one critic put it in his review of Teatro delle Mostre, it meant “a big acceleration of what art criticism calls art as process”.

Art as process: four days, three performances and one installation

Giosetta Fioroni

Thursday 4 May

Just as Fioroni inaugurated Teatre delle Mostre, she will open the Frieze Projects tribute. On the first public day of the fair, her La Spia Ottica (1968) will be recreated and viewers invited to “spy on the life of a woman in her seductive and ordinary everyday intimateness”, Fioroni says. The artist considers the work especially important in her career arc, in part because “it has been one of my very few performances.” Prior to the 1968 work, Fioroni was known primarily for her paintings. With the performance, she says, “I was trying to grasp an idea of femininity, and not feminism, as many others were doing at the same time.”

Ryan McNamara

Friday 5 May

McNamara’s performance responds directly to Fioroni’s. In place of Fioroni’s bed, McNamara will install a stage from which an actor will give instructions to eight others. Along the walls of the booth, McNamara will place domestic objects that could conceivably exist in Fioroni’s bedroom. “I wanted to do some mirroring,” McNamara says, adding that there will also be major differences between the two works. His performers will patrol the fair with latex masks of their own faces. “The booth is sanctuary for these humanoid creatures,” he says. “Once they need to go to their rejuvenation station, they head back to the room, where they are allowed to shed their human skin.”

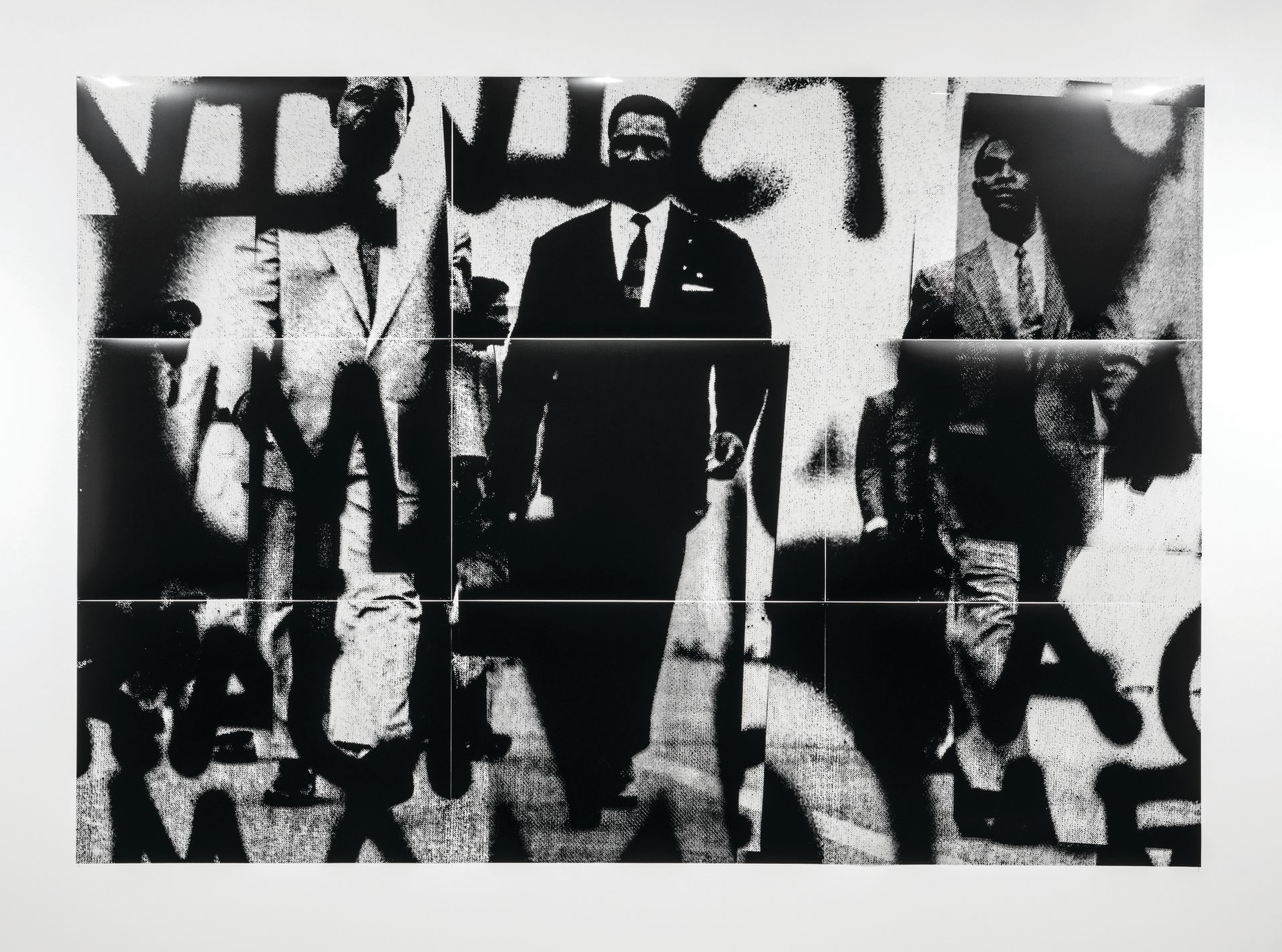

Adam Pendleton

Saturday 6 May

“When I’m presented with the idea of responding to historical material, I think of parallel tracks, rather than trying to get into the same lane,” Pendleton says of his performance, which is done in collaboration with the singer and songwriter Alicia Hall Moran. With a string quartet and two gospel singers, Moran will perform an aria she composed, for which Pendleton wrote the libretto. “The booth will be on the spare side,” Pendleton says, focused on an installation based on an earlier collage of his that will “function like a traditional theatrical backdrop”. His libretto is also based on an earlier work: it expands on his 2007 Performa commission, The Revival, which was the first project he collaborated on with Moran.

Fabio Mauri

Sunday 7 May

On the final day of the fair, organisers will restage Mauri’s Luna (1968), which will be installed “just like it was, in a dark room, with a black ceiling and two portals” through which visitors can enter the space, according to Alemani. The booth will be filled with Styrofoam “pearls”, which in the original work came up to one’s knees. In retrospect, Mauri’s work was prescient: he first staged it more than a year before the Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969. Luna also provided a new outlet for Mauri’s performative work (in addition to being an artist, he was a playwright). The work will be installed in consultation with his estate.