Annette Messager: Avec et sans raisons, Marian Goodman Gallery, London (until 27 May)

Annette Messager may now be in her 70s but she’s more exuberant than ever. In this gathering of rumbustious recent work, the everyday turns nasty and body parts run riot. Floppy figures made from flaccid stockings cling pathetically to outsized objects—scissors, a hammer, earphones, a handbag— that are sown out of shiny black leatherette and dangle from the ceiling, with their sadomasochistic undertones amplified by an infestation of netted rats at floor level. Barbie dolls are chopped up, painted black and pierced by hooks, while a wooden Pinocchio doll is strung up and engulfed by his own stuffed fabric entrails.

The female body dominates throughout this exhibition with an often hilarious ferocity. One room is lined with wallpaper printed with delicately coloured uteruses, some with fallopian tubes that end in a flicking middle finger. This up-yours uterus also reappears as a soft sculpture, while another uterus sculpture dons a tutu and is blown around the room by an electric fan. Things get more angry in watery acrylic paintings of menstruating women emblazoned with the words “Bloody Mary” or “My Ketchup”. These are joined by bobbing rows of breasts and pictures referring to the Ukrainian group Femen, whose naked torsos carry slogans such as “Fuck Your Morals” and “I am my Own Prophet”. In the world of Messager, nuns go topless and paint “In Gay we Trust” across their breasts. But while it’s hard not to applaud the vehemence of this one-woman pussy riot, at times her fury can tip into farce.

Double Take, Skarstedt Gallery, London (until 27 May)

An important and tightly curated show examining how the practice of appropriating existing photographic images has evolved from the so-called Pictures Generation of the late 1970s and early 1980s—Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler—to be reinterpreted and expanded by a new generation of younger artists. In a line-up spanning more than half a century, it is fascinating to plot the many and various ways in which printed pictures plucked from our ever-proliferating visual glut have been reproduced, reframed and then reintroduced back into our collective cultural consciousness, armed with additional message and meaning.

Here, varying forms of appropriation can often be underpinned by shared preoccupations. Explorations of representation through the image of the female body range from Robert Heinecken’s 1963-67 photograms of fashion models lifted and superimposed from magazines, through to Louise Lawler’s 2002-03 photograph of Gerhard Richter’s painting Ema (Nude on a Staircase) (1966), ignominiously lying on its side and propped against MoMA’s wall. And most recently, Anne Collier’s double image of a female nude re-photographed last year from the endpapers of an art book. There’s also an especially potent confluence of desire, aspiration and cliché to be found both in Richard Prince’s now-classic cowboys and Steven Shearer’s collaged multitude of Guys. In the latter, the occasional recognisable celebrity, such as the late hellraising English actor Oliver Reed, pop up amidst a sea of unknown male faces lifted off the internet. In today’s visual glut where truth and reality and the meaning of what we are seeing becomes evermore nebulous, Barbara Kruger’s 1983 statement “Your Fact is Stranger than Fiction” still seems especially apt.

Art/Africa: the New Atelier, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (until 28 August)

Art from Africa continues to be woefully under represented throughout the contemporary art world and so although it gives a highly partial—and some might say flawed—view, the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s exploration of the African continent is therefore still most welcome. The first section of this three show survey is devoted to 15 sub-Saharan artists taken from the collection of the playboy-businessman Jean Pigozzi, which he built up in close association with the curator André Magnin between 1989-2009.

Some are now familiar, such as the vivid paintings of the Congolese artist and former sign painter Chéri Samba; the Benin-born Romuald Hazoumé’s caricatured masks made from customised jerry cans; and the Malian photographer Seydou Keita. Others less so: the elaborate cardboard and plastic fantasy buildings of Bodys Isek Kingelez and the terracotta totem figures made on an open fire kiln by the Senegalese septuagenarian Seni Awa Camara were a particular revelation. Despite the Pigozzi collection being criticised for focusing on traditional handicrafts and self-taught artists “unpolluted” by Western art education, it has been crucial in gathering such a range of powerful and original voices, many of whom owe their current profile to Magnin’s energetic fieldwork.

Pigozzi’s collection is both complemented and complicated by a second show devoted solely to contemporary art from South Africa, which encompasses three generations and demonstrates a more active engagement in the country’s social and political scene. From the effects and direct legacies of apartheid, it offers an often coruscating insight into the role of the artist-activist within a nation still deeply divided and struggling with its past. These issues are addressed in the work of leading older figures such as William Kentridge, David Goldblatt, Sue Williamson and Jane Alexander, through to younger “born free” artists such as Zanele Muholi, who critiques clichéd images of black women. Muholi has made an extensive photographic study of the country’s lesbian community.

Both these shows are accompanied by a presentation of works by artists from Africa or with African backgrounds, all of which are owned by Fondation Louis Vuitton. These represent a wider diaspora and tend to have a higher international profile such as Wangechi Mutu, who divides her time between Nairobi and New York; the US artist Rashid Johnson; the British painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye; as well as a reappearance by artists such as David Goldblatt and Chéri Samba. All in all, an important reminder of the immense complexity and diversity of art from all the cultures and countries of Africa and how much work still needs to be done to ensure it is properly integrated within the global art world.

David Batchelor: Psychogeometry, Matt’s Gallery, London (until 11 June)

David Batchelor is an artist who is primarily concerned with colour and the often unexpected brilliance of the urban environment. He’s made sculpture out of the cheapest, trashiest plastic goods, as well as multi-coloured light boxes using salvaged industrial materials. These are joined by illuminated wall pieces made from geometric multi-coloured LED elements and mundane objects rendered flashily glamorous by being outlined in vivid neon.

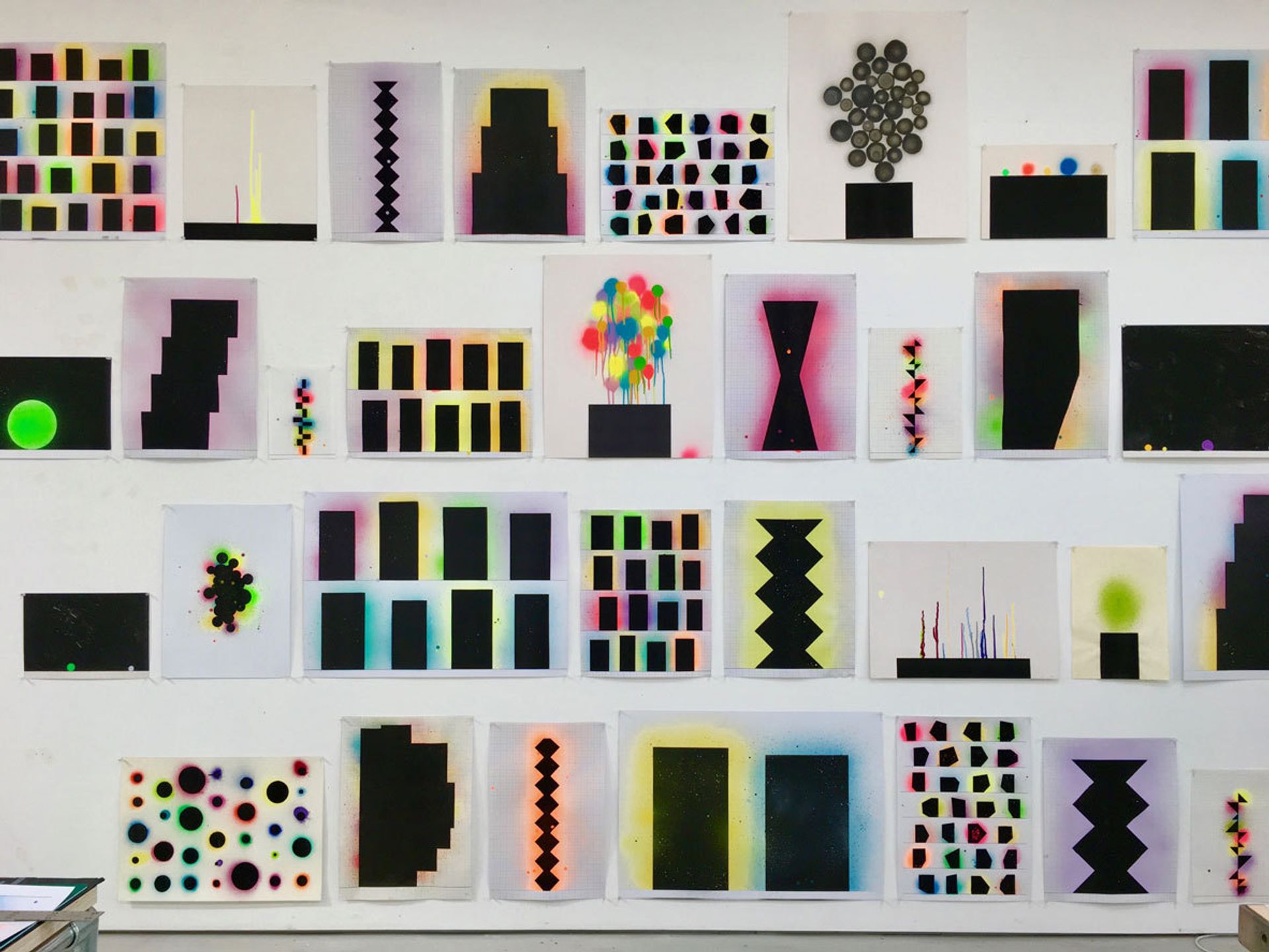

Not only does Batchelor’s work revel in intense colour, it is also concerned with examining how we perceive and respond to its retina-sizzling qualities—especially in our technological age. These investigations continue in his current show at Matt’s Gallery. Here, in Batchelor’s first-ever wall drawings, mists of fluorescent colour glow around the edges of rectangular stencilled blocks of matt black, conjuring up a vivid experience of darkness and light without the need of electricity. The environment is further complicated by a series of freestanding painted sculptures made from squares, circles and angular corners cut out from the cheapest builder’s yard timber, plywood and MDF.

The three-dimensional stacks and screens of geometric shapes are coated in a thick, gloppy, tarry covering of black household gloss. These works filter and articulate the space, and give off a strong totemic presence that belies their throwaway origins. It’s testament both to Batchelor’s rigour and his sense of play that such seemingly simple components can act so effectively on the instincts as well as the intellect.