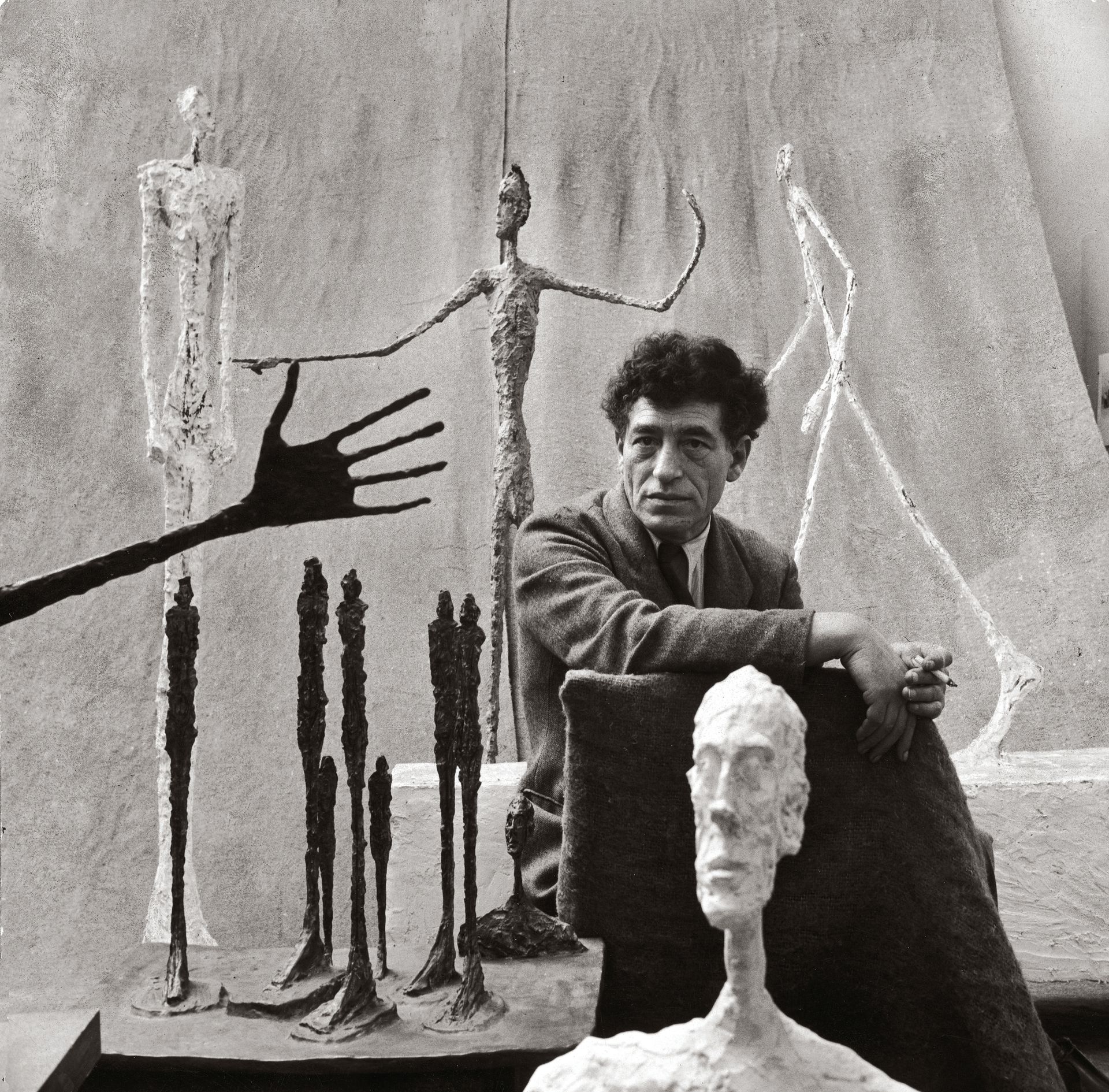

The other Giacometti.” This is how the art critic Michael Brenson described Diego, the younger brother of the Swiss-born sculptor Alberto Giacometti, in the New York Times 33 years ago. Alberto needs little introduction, as a major survey at Tate Modern, opening this month, reflects. After having shown his interest in Cubism, he joined the Surrealist movement in 1931 but his major breakthrough came later; in 1944, he started work on the Woman with Chariot, borrowing from the memory of his friend Isabel Nicholas. With her expressionless face, she became the prototype of the tall, thin post-war standing figures that made his celebrity. Alberto died of a heart attack in 1966 at the age of 65.

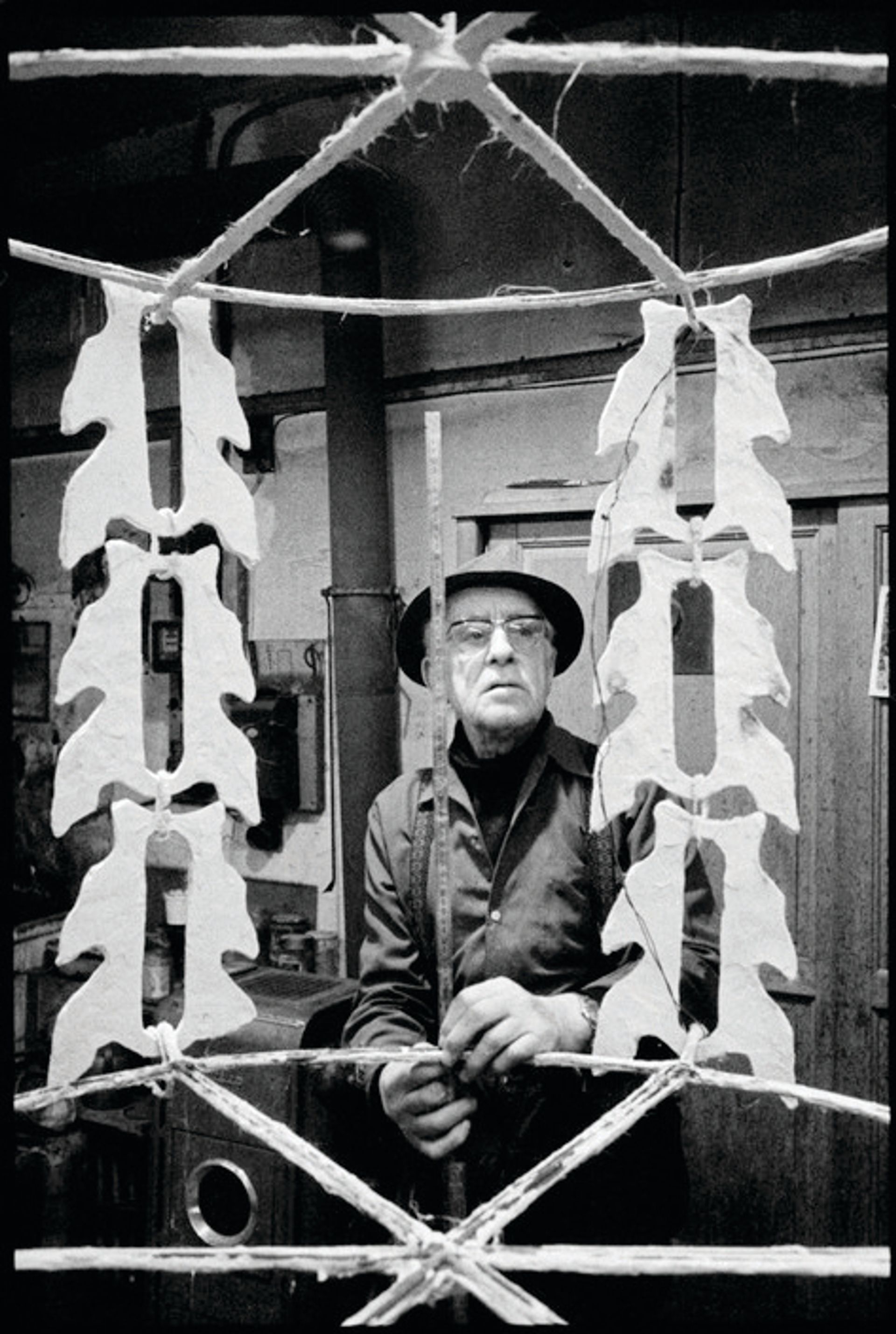

Diego, who died in 1985 at the age of 82, began producing his own bronzes and furniture relatively late in his life, inspired by the creations of his brother, but more whimsical and with stiffer lines. Sotheby’s in Paris will hold a sale dedicated to Diego’s work later this month.

In his lifetime, they found their way to the houses of the Mellons and Hubert de Givenchy, among other leading collectors. He received commissions from the Chagall Museum in Nice, the Maeght Foundation and the Picasso Museum, Paris, in the year of his death. “Every day, Diego sketches, makes armatures, fiddles with plaster animals, patinates bronze. It is all second nature to him now, but the curiosity and hunger of his hands have not begun to be satisfied,” wrote Brenson the year before. “One cannot imagine Alberto without Diego,” Brenson tells The Art Newspaper today. He met Diego in 1970 through James Lord, whose Giacometti biography would be published in 1985. Brenson says that Diego was “very generous” to him. He had “a very practical mind and a certain toughness. He was a bit gruff, but also mischievous, deceptively worldly and capable of great joy and warmth. For a long time, pretty much all of Alberto’s sculpture came through Diego’s hands. The value of such help is incalculable. But the affective bond they shared was also indispensable. They came from such a different world in Switzerland.”

Alpine Youth They were both born in Borgonovo, near the Italian border; Alberto in 1901, Diego 13 months later. Alberto was the first child of Giovanni and Annetta. Their sister Ottilia was born in 1904. The youngest brother, Bruno, born in 1907, became an architect based in Zurich.

Giovanni Giacometti’s influence on his children cannot be overestimated. A Post-Impressionist painter, he stayed up to date on news of the artistic movements throughout Europe. He was friends with the two foremost Swiss symbolist painters, Cuno Amiet, who became Alberto’s godfather, and Ferdinand Hodler, Bruno’s godfather. Diego’s godfather was the village schoolmaster. The family lived in Stampa, where they owned an albergo (hotel), spending summer holidays in Maloja, on Lake Sils.

Skilled at drawing, Alberto would spend his time copying engravings from his father’s library and making sketches in the Alps, while Diego preferred to walk in the mountains and valleys of their childhood. Alberto’s first bust, made when he was 14, was of his brother; he kept it all his life. “At first, I felt an intense pleasure. I thought that it would be quite easy and I would be able to reproduce more or less what I saw... Fifty years later, I still feel I never succeeded in this,” he said in 1962.

Encouraged by his father, Alberto arrived in Paris in January 1922 to enrol at the academy founded by the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. Giovanni was thrilled by his selection for the Salon des Tuileries in 1927: “I have always dreamed of conquering Paris,” he wrote in a letter. “Now you three are making this conquest, with sculpture, industry and architecture.” The “industry” part was Diego’s destiny. He had briefly worked for an industrial designer. So the father was framing the ambitions for his sons, but Diego found it hard to live up to his expectations. After studying at a business school in Basel, he returned to his parents’ home. Later, he mingled with dubious company in Marseille. He painted for a while. When, at the request of his mother, he finally settled in Paris in 1930, it became clear that he was being placed under his older brother’s charge. “Alberto had helped Diego since childhood,” said Lord. He found a place for him to live on the other side of the courtyard of his studio in Montparnasse, on rue Hippolyte-Maindron.

Happy accidents Alberto pushed his brother to learn the techniques of sculpture, hoping he would thus be able to free himself from his dependence on the mould-makers. Diego started to make the supporting frameworks and moulds for his brother’s sculptures. When Alberto received a commission for a 2.4m figure for the gardens of the Noailles on the Riviera, Diego helped shape the marble, which Alberto then chiselled. Later, his brother looked after the relationship with the bronze foundries. In the mid-1950s, he also prepared and applied the patina for some of the bronze casts.

“Diego really became a great asset to Alberto after the Second World War,” says Véronique Wiesinger, who led the Alberto & Annette Giacometti Foundation in Paris from its beginnings in 2003 until 2014. (Alberto had married Annette Arm in 1949.) “Through him, Alberto was finally able to control his own plaster casts and patinas. And if there were imperfections, that was fine because he thought accidents should be part of the work, even adding a Surrealist touch.”

Alberto never ceased modelling Diego’s head. On 14 February 1935, he wrote to his mother that he was working on a bust of him. The very same day, he was expelled from the Surrealist group, partly for working from a live model. “A head! Everyone knows what a head is!” exclaimed André Breton at the time to Simone de Beauvoir. It surprises now, given that human heads, and especially the eyes, are at the centre of Giacometti’s creation.

But was it really Diego’s head—anyone’s head—he was working on? “I must virtually be alone to sculpt busts based on live models—of Diego or Annette,” Alberto also said. “But if my wife is my model, after two or three days, she does not look like herself... People buying my pieces do not buy my busts because they are meant to look like the model, but because they believe it is an invention, a complete invention.” Nonetheless, there was a “small degree of resemblance”, he conceded.

“He blurs the lines: he dematerialises the sculpture, in order to show us what he sees,” says Wiesinger about his portraits. “He tries to get as close as possible to his vision, with the intensity of his own perception.” As the French playwright and poet Jean Genet wrote: “Alberto Giacometti’s busts must be seen from the front. The significance of the face—its profound resemblance—cannot be seized; it sinks deeply, to a place never to be reached, beyond the bust itself.”

The brothers were separated during the Second World War. In January 1942, Alberto returned to Switzerland, while Diego remained in Paris. At the time, Diego was living on the sales of his brother’s bronzes, which were not numbered as part of a limited edition, as happens today. But he was also designing his own objects, which he kept almost secret for decades. “Beautiful sculptures.” wrote Nicholas in her memoirs. “I was lucky to see them. Very few people did. He hated showing them to any but a few close friends.” After Alberto created a dog, a cat and a pair of horses in 1951, he turned away from animal subjects to leave them to his brother. They decorate many of Diego’s most sought-after pieces of furniture.

By the late 1950s, Alberto’s reputation had made him world famous. US collectors were seduced by this charming man with his chiselled features, who had a slight limp and kept his Italian accent. Photographers like Cartier-Bresson or Irving Penn widely published images of the artist in his small crowded studio—the epitome of bohemian Paris.

Diego’s role in his brother’s production took on increasing importance. “He is for his brother the awakening and supporting mind on all occasions,” said Herta Wescher, a one-time neighbour. “Along with Annette, he is the most available and patient model, but he is also in charge of a thousand practical things. He makes sure appointments are respected. He gets rid of unwelcome visitors. But above all, no work is born without deep discussion between the two, Alberto’s repeated questions clearly audible, unlike Diego’s, who is not the sort of person to speak so loudly.”

However, when their mother asked Alberto in 1947 if he could sign his works with both names, he replied very clearly: “Obviously, I have to exhibit under my name only—even if Diego is helping me. Diego also shows and sells what he is doing and conceiving under his name, even if I help him. In both cases, the one who helps is subordinate to the other’s concept.” The artist insisted they were fully in agreement on the matter.

“Diego answered with eloquence and often in detail to questions about technical matters and material. But whenever I asked him about the meanings of his brother’s Cubist and Surrealist works, he felt uncomfortable,” Brenson recalls. “He held his brother’s work in high esteem. I never heard him complain about anything to do with his work. But after a while I had a strong sense that questions that depended upon experiencing and interpreting art were foreign to him. Diego’s response to Alberto’s embrace of impossibility was complicated. He both admired and was irritated by it.”

The Caroline bombshell Their relationship became more difficult as Alberto’s fame grew. To reach the artist, many thought they had to go through his brother. “When Alberto got too busy, his dealers like Pierre Matisse or Aimé Maeght would rely heavily on him to get and ship the bronze editions,” says Wiesinger. “Some collectors like G. David Thompson would be quite rude and ignore Diego... he must have suffered from this situation, especially when he was trying to make his own creations.”

Everything changed in the early 1960s, to the point where Diego even refused to continue modelling for Alberto, who then sculpted his brother’s face from memory, mixing it with other characters, including feminine figures. Only the wide eyes and a faint smile remained distinctly his brother’s. In 1961, Diego also started in earnest to produce his own works. The catalyst for this change was named Caroline. In 1959, Alberto fell in love with the 20-year-old courtesan from Montparnasse. He travelled with her and gave her money. In 1960, after she spent a few months in jail, Alberto offered her a red MG Cabriolet. “Alberto,” says Wiesinger, “had a very strange relationship with money. He could be very generous with others, but the relationship with Annette and Diego was different. He gave very little to his brother for all his work, and the same with Annette.” Lord once said that “for Alberto, having Diego was like having four hands”. It was as if he and Annette were extensions of himself in the making of his oeuvre. When her husband offered an apartment to Caroline, Annette, who had never asked for anything for herself, made him buy one for her in Montparnasse. “Caroline blasted the planet Giacometti, one could say,” says Wiesinger. “But the real roots of this upheaval can be found in Alberto himself.”

This became even more obvious after his death. The artist never made any plans for his collection; everything was in his name, and he had not made a will. It was left to Annette to take charge of his legacy. The foundation finally came into being a decade after her own death. Diego occupied a studio in rue du Moulin-Vert, which had been purchased by Alberto and Annette in 1961 for big formats and which also served as a storage space for old works and plaster casts. The notary who inventoried Alberto’s possessions in detail after his death was not authorised to list his works there. “To be continued”, stated his inventory. Annette let it go. She was already busy fighting against the numerous forgeries appearing on the market.

Unsavoury characters Diego sold most of his brother’s possessions, including plasters that were part of the joint heritage. For instance, the 1932 modello for Hour of the Traces, now at Tate Modern, which he put under auction, was never listed on the inheritance inventory. Diego was also allowed by Annette to continue his own production of his brother’s bronze lamps, which he conducted with various foundries—a rather unscrupulous milieu. These bronzes flourished; some were unauthorised or even counterfeited. He sometimes signed certificates for Alberto’s works. Finally, it seemed, Diego’s time in the sun had come. He joined the glamorous set, mingling with the likes of Givenchy or the cinema producer Raoul Lévy. But there was a darker side of the story. In his final years, he was surrounded by several unsavoury characters, who profited from his influence and even stole from him.

Diego became the centre of a mythology which spread on the market. “There are tales like him having a hidden son or overruling Alberto on what not to destroy of his output, which is insane. Alberto’s instructions on the matter were extremely precise,” Wiesinger says. Diego’s name was used by dealers willing to sell unregistered bronzes. As there was no precise inventory, after his death he became a miraculous source for the unscrupulous. A German forger, Lothar Senke, who was sentenced to nine years’ jail in 2011, even claimed that he received hundreds of objects and casts from Diego, and published a book pretending that he was the real genius of the two brothers. To a lesser extent, various experts have proposed (wrongly) that Diego might have been involved in Alberto’s creations. “Diego was a superb craftsman with flair and wit who invented his own fanciful world; his objects will survive, but he did not have his brother’s imagination, drive, ambition or purpose,” Brenson says. “Alberto had a deep culture; he was at home with philosophy and poetry and steeped in the history of art. He never goes away. He’s always contemporary—an inexhaustible figure.”

• Giacometti, Tate Modern, London, 10 May-10 September; Diego Giacometti sale, Sotheby’s Paris, 17 May, works exhibited 12-16 May