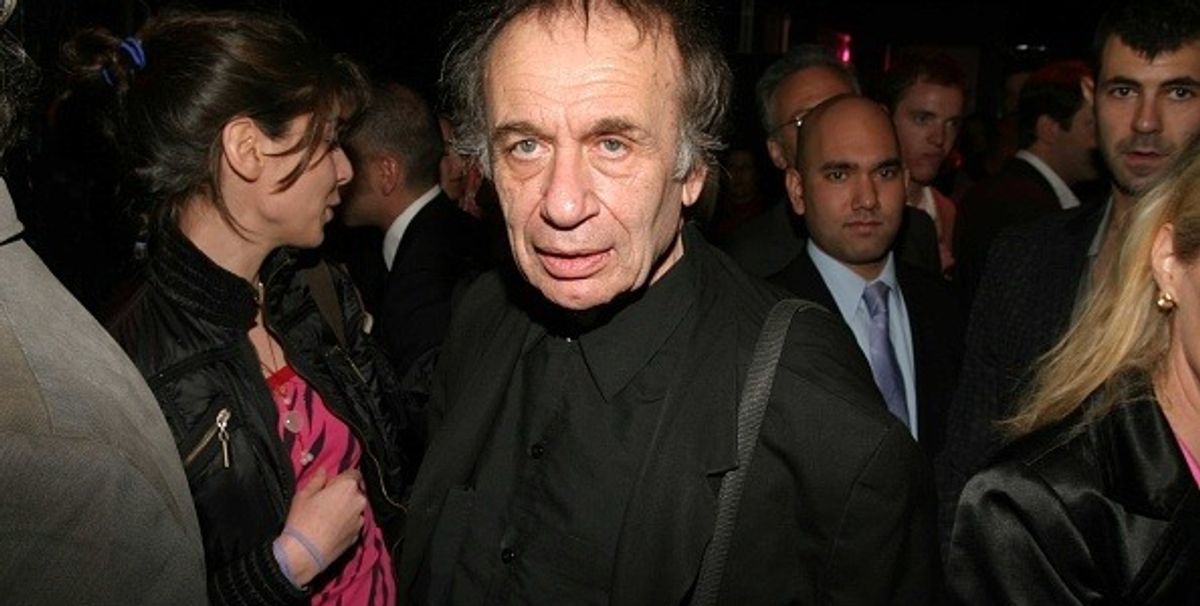

The US artist and architect Vito Acconci, known for his radical conceptual works such as Seedbed (1972), has died age 77. The Bronx-born artist turned poet and architect, who is considered a Body Art trailblazer, arguably paved the way for a later generation of artists such as Martin Kippenberger, Matthew Barney and Paul McCarthy.

Acconci received his BA with a major in literature from Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1962. After publishing a magazine called 0 to 9 from 1967 to 1969, he turned to photography, documenting passers-by that he followed on the street for the work Following Piece (1969). The work explores “his body’s occupancy of public space through the execution of preconceived actions or activities”, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which owns photographs from the series. For Seedbed, he spent hours masturbating beneath a ramp at the Sonnabend gallery in New York while whispering aloud his fantasies about visitors.

From the late 1970s, he began making experimental sculptures, furniture and public art pieces, including Birth of the Car/Birth of the Boat (1988) located in Pittsburgh, Name Calling Chair (1990) and Flying Floors at Philadelphia International Airport which was unveiled in 1988. The same year, he established his own architecture practice, Acconci Studio, which is based in Brooklyn.

Last year, MoMA PS1 in New York presented a survey of Acconci’s works of the 1960s and 1970s, exploring the artist’s early poetry, sound and video pieces. The show—Vito Acconci: Where we are now (Who are we anyway?) 1976—included the Super 8 film Shadow Play (1970) in which Acconci shadowboxed in front of a blinding light, and the film Openings (1970) which showed the artist pulling out his body hair. Klaus Biesenbach, the director of MoMA PS1, told The New York Times last year: “He’s challenging our limits about what we want to be private and what we want to be public, and those questions have only become more important.”

Acconci talked to The Art Newspaper in 2002 when he reflected on his early career. The artist said: “After college, I went to a writing school at the University of Iowa. After that, I came back to New York in 1964 and that was the first time I realised art galleries existed. That was when I saw a Jasper Johns painting for the first time… Jasper Johns was the big influence, the notion of how to make abstraction possible using convention first, use a flag, use a number 5, as long as you have that you can make any impression you like, as long as you have the given. It so shaped the way I thought, it made me recognise conventions, that there’s no such thing as ‘creation’ just organisation and re-organisation, dis-organisation.”

Asked whether he thought he should subsequently make art, he said: “I thought I had no desire to make art. But I realised when I was writing I was using the page as something to travel over and that if I was so interested in moving across this space I should move over a floor, over a street, a ground. But also by 1967, phrases like ‘conceptual art’ were first being used. If conceptual art hadn’t been around there wouldn’t have been any place for me. Entrance is only possible at certain times and in certain contexts. I couldn’t draw, I couldn’t paint, I couldn’t build but once someone said conceptual art I thought maybe I can do that, I have ideas, there’s a place for me.”