Films about art tend to be documentaries, yet Tribeca is screening some more cinematic alternatives.

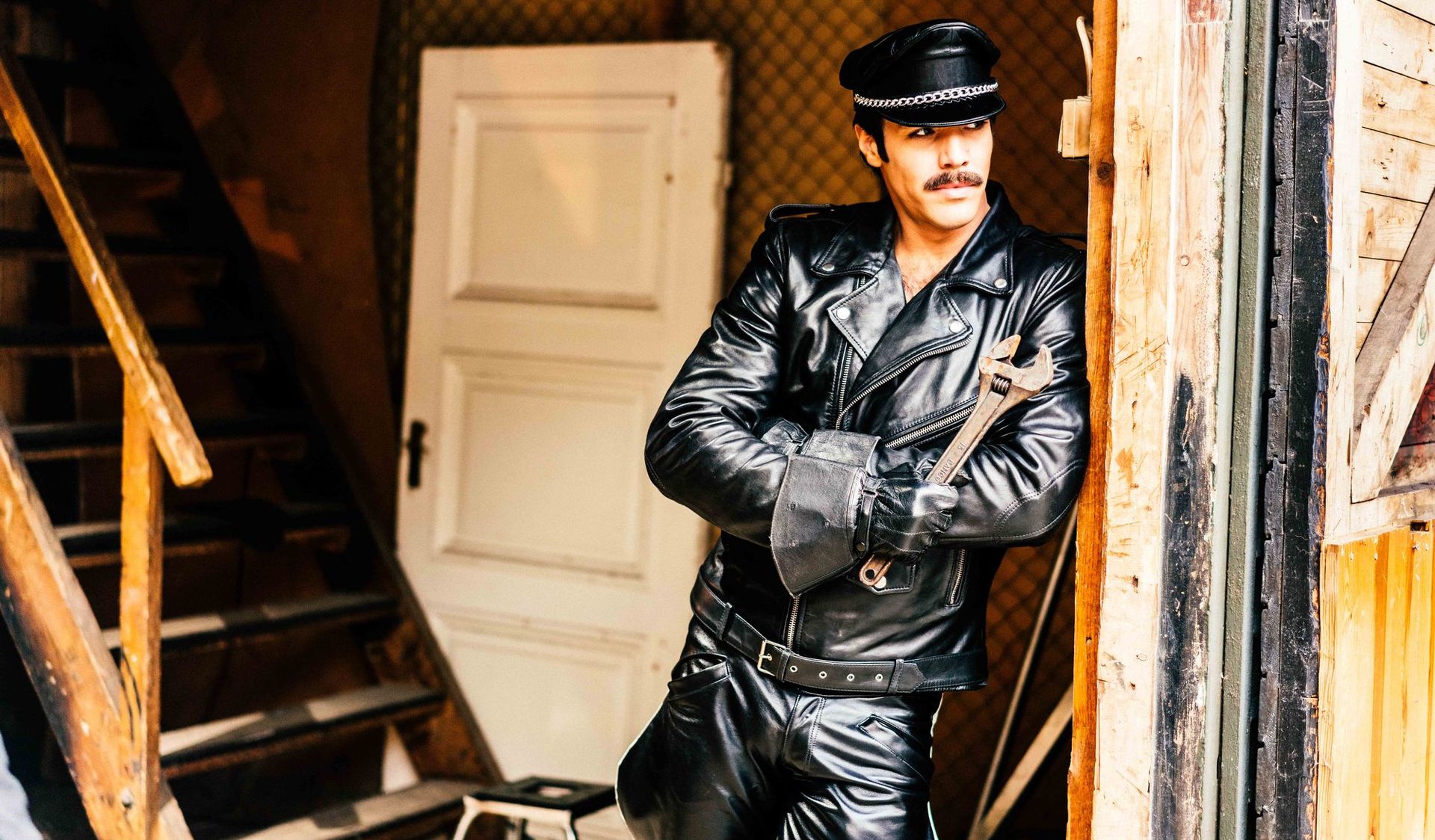

Tom of Finland, a dramatic biopic, promises that there is more to know about the work of Touko “Tom” Laaksonen (1920-91) than muscled men bulging out of their leather jackets and britches. The Finnish director Dome Karukoski gives us the life of the slight, withdrawn young man who discovered gay sex in the Finnish army (on Hitler’s side) during the Second World War and eventually created a brazen template for a swaggering homoerotic identity. There are still plenty of signature Tom bodies here in an international co-production with a remarkably commercial look, given a subject that mainstream cinema would have once shunned. Awarded a prize at its premiere in Sweden this winter, Tom of Finland is evidence of a taboo finding and flaunting its way into the mainstream.

In My Art, another scripted dramatic look at an artist’s working life, debut director (and veteran artist) Laurie Simmons casts herself in the role of a woman who decamps from New York City for a stay in the country. The story, written by Simmons, takes the audience into the challenges faced by women artists, with the drama arising from the character removing herself from her element in the city, in the vein of Ingmar Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer Night or Woody Allen’s A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy. Simmons is not new to film. She played a working artist and mother of two daughters in Tiny Furniture (2010), the well-received independent comedy written and directed by and starring her daughter, Lena Dunham, who went on to create the HBO series Girls.

On the documentary side, the dutiful Blurred Lines: Inside the Art World offers an entry-level focus on art and money in the contemporary art market. Of greater interest is Shadowman, by Oren Jacoby, which could also be called Survivor. It is a portrait of Richard Hambleton, a graffiti artist famous for his splashy threatening silhouettes of men in black that appeared on walls in downtown Manhattan in the early 1980s.

Hambleton got more media hype than Keith Haring or Jean-Michel Basquiat back then, yet his drug addiction and obsessional intransigence aborted one revival of his career after another. Hambleton disappeared from sight for years in the 1990s. “At least Basquiat died. I was alive when I died, that’s the problem,” he reflects on camera. Persistent dealers, backed by the fashion designer Giorgio Armani, eventually managed to monetise the self-destructive Hambleton, who still works on the Lower East Side. The biggest shock for those who knew him is likely to be that Hambleton is still alive.

At the other end of the success spectrum is Julian Schnabel, also the subject of a documentary at Tribeca. Julian Schnabel: A Private Portrait is a career retrospective of the man in full, as Schnabel discusses his life in painting and revisits his rise to art celebrity in the 1980s, followed by his entry into filmmaking in the 1990s. The film, directed by Pappi Corsicato, draws on an extensive archive of images dating back to Schnabel’s childhood. Context comes from Schnabel’s family, and from such peers as gallerists Mary Boone, and fellow artists Jeff Koons and Laurie Anderson. Rarely has a private portrait been so public. The film opens generally in New York cinemas on 5 May.