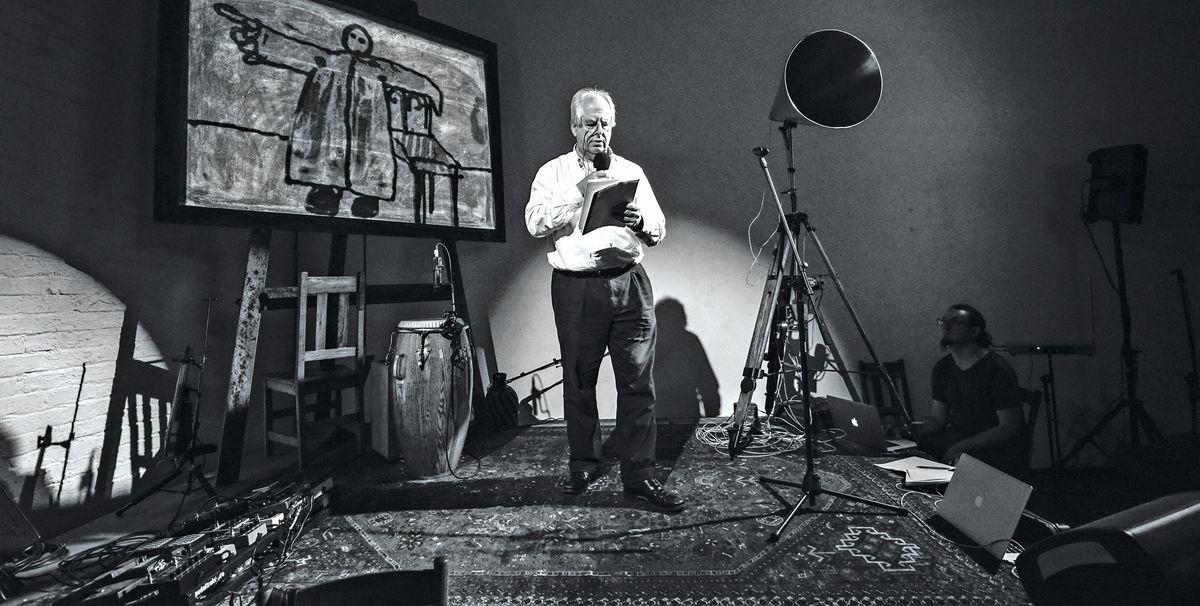

The South African artist William Kentridge has set up an arts foundation near his studio in Johannesburg, providing a “safe space for uncertainty, doubt, stupidity and, at times, failure”, he says.

The artist has called his foundation the Centre for the Less Good Idea—a reference to the process of creation, which often sees artists derailed from exploring their initial idea and focusing on “secondary ideas that emerge during the process of making”, he says.

He set up his foundation in the Arts on Main complex, a converted warehouse in central Johannesburg, which houses his studio as well as other art spaces. It aims to answer a real need in the city and across the country for alternatives to beleaguered public art spaces.

“There’s a sense in Johannesburg and South Africa that the public funding of institutions is collapsing,” Kentridge says. “The Johannesburg Art Gallery, the gallery of my childhood, which has a wonderful collection of South African and African art as well as Rembrandt prints and other things, closed down in February. It had a new roof put up, but this was made of copper, which is a highly desirable material, so the roof was removed by thieves in the night, and then the rain came and did irreparable damage to many of the galleries.”

The new centre’s inaugural season of performances, film screenings and art displays took place in March, organised by the theatre director and playwright Khayelihle Dominique Gumede, the poet, author and activist Lebogang Mashile, the dancer-choreographer Gregory Maqoma, and Kentridge himself. It brought together 60 participants including actors, dancers, poets, writers, artists, composers, film-makers and boxers. They worked together to create a series of public performances, including the staging of four plays by Samuel Beckett, a work by the Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka, a parade, and a series of performances in collaboration with a local boxing club.

“It’s a small arts centre, the budget is modest, but it should enable us to have two seasons a year, the seasons being defined by the different curators who run them,” Kentridge says.

According to reports in the South African press, Kentridge has committed to fund the organisation with R3m ($229,000) a year for the next three years, but he declined to confirm the figure.

Freedom to explore Kentridge hopes to give creative individuals the freedom to explore their ideas without having to conform to anyone else’s agenda. When non-governmental bodies (NGOs) fund arts projects in South Africa, “the work that is done is always shaped by the needs of the NGOs and the demands of what has to appear in the proposals of the different organisations, which is not the way a lot of art happens at its best”, Kentridge says.

Artists should follow their instincts, he says, and listen to the ideas of other creative individuals, even if the results are not always successful. “Of the 19 performances we did in the first season, between four and six were spectacular. There were other performances that felt really solid and imaginative, and some that were about testing things out, some of which worked less successfully.”

Kentridge says his own artistic failures have made him the artist he is today. “In my own life, there have been many, many failures. I wanted to paint in oil paints, I failed at that. I went to Paris to become an actor, I failed at that too. I wanted to make films and write film scripts, and I also failed at that. And I was reduced to being an artist. Yet many years later I discovered that all these different areas in which I had tried to specialise and make a life for myself, all of these failures in fact provided very rich material.”

The centre’s second season will again, he says, “have a strong performative element, as this is the way in which audiences gather together and a sense of community is fostered much more potently than at the opening of an art exhibition”. The focus will be on “work with electronic engineers and performers and artists”.

He adds: “Ideally, we would have double the space and double the money, but I think the small scale is also good. As soon as it gets larger it gets lost in questions of committees and trustees, and suddenly everyone is having to write big proposals to justify their work before it is made rather than allowing the work to come from the very uncertainty around it.”