Stephan Balkenhol and Lisa Brice, Stephen Friedman Gallery (until 22 April)

Both Stephan Balkenhol and Lisa Brice engage with everyday reality via the human figure, with Balkenhol and his rough-hewn painted wooden sculptures the better-known of the two. But I was especially struck by Lisa Brice’s 54 gouaches devoted to women in various states of undress, which process around the walls of the gallery’s second space. All painted in a vivid cobalt blue, this series of self-possessed, unselfconscious women reclaim the traditionally prurient subject of women undressing (invariably observed by men) and re-present it in terms of confident female empowerment.

The use of blue—unmixed, straight from the tube—provides a certain illustrative distancing from these intimate scenes, as well as conjuring up a memory of Matisse’s blue nudes. Yet, while some of their gestures and the poses they strike can chime with art history—in a couple of pieces there’s a significant nod to Degas and Balthus—the women here are emphatically modern. They smoke, dance and stand around in their underwear. They examine themselves in the mirror, adjust their hair and get changed in convivial groups. At times they can be solitary, thoughtful and introspective but never passive. Brice’s fluid, spare and highly accomplished draughtsmanship underpins these works—they are simple, uncluttered and matter-of-fact. Her women claim their beauty and their bodies on their own terms.

Richard Mosse: Incoming, Barbican (until 23 April)

Richard Mosse’s new film turns the latest thermal surveillance technology, developed by the military, onto the refugee crisis. Using a special camera that that can pick up a human presence at 30km and is often attached to weaponry, he films—amongst other things—a makeshift camp in Berlin’s former Tempelhof Airport; trucks packed with people driving across the Sahara; refugee boats in the Aegean Sea; and a US aircraft carrier and jet fighter in the Persian Gulf.

When shot with a camera that is colour blind and only registers heat, all sorts of strange things happen. The hotter a body, the whiter it becomes and veins under the skin give a face a marbled effect. People become weirdly translucent, monochrome spectres, as what you see is governed by their secretions and heat distribution. Patches of sweat form dark smudges. Sometimes you can see a woman’s hair through her hijab. Water becomes blood-like. This weirdly intimate, but also emphatically objective, view of humanity disconcertingly manages to be both highly intrusive and utterly detached. It is also problematically mesmerising, especially when magnified and projected over three, eight-metre-wide screens and accompanied by the composer Ben Frost’s thunderous electronic soundtrack.

Mosse wants to challenge documentary photography and make us aware of our “uneasy complicity” in the horror of this humanitarian catastrophe that is displacing more people now than after the Second World War. His film and accompanying photographs certainly made me feel uneasy. But this was largely because the effect of his elaborate and spectacular missile’s-eye view just seemed to further dehumanise these individuals and to reduce the horror and complexity of their circumstances to a series of abstractions. And isn’t this already the treatment they are receiving at the hands of the international community?

Electricity: the Spark of Life, Wellcome Collection (until 25 June)

This is the latest in a long line of ambitious thematic shows that imaginatively erode the boundaries between science and art by combining commissions from leading contemporary artists with objects and artworks belonging to the Wellcome Collection’s extensive medical collections. Earlier topics have included death, dreaming, madness and drugs. And now it is the story of mankind’s quest to understand, unlock and master the power of electricity that is under scrutiny, with the artists John Gerrard, Camille Henrot and Bill Morrison each invited to make new work on the subject of what is, after all, the energy of life itself.

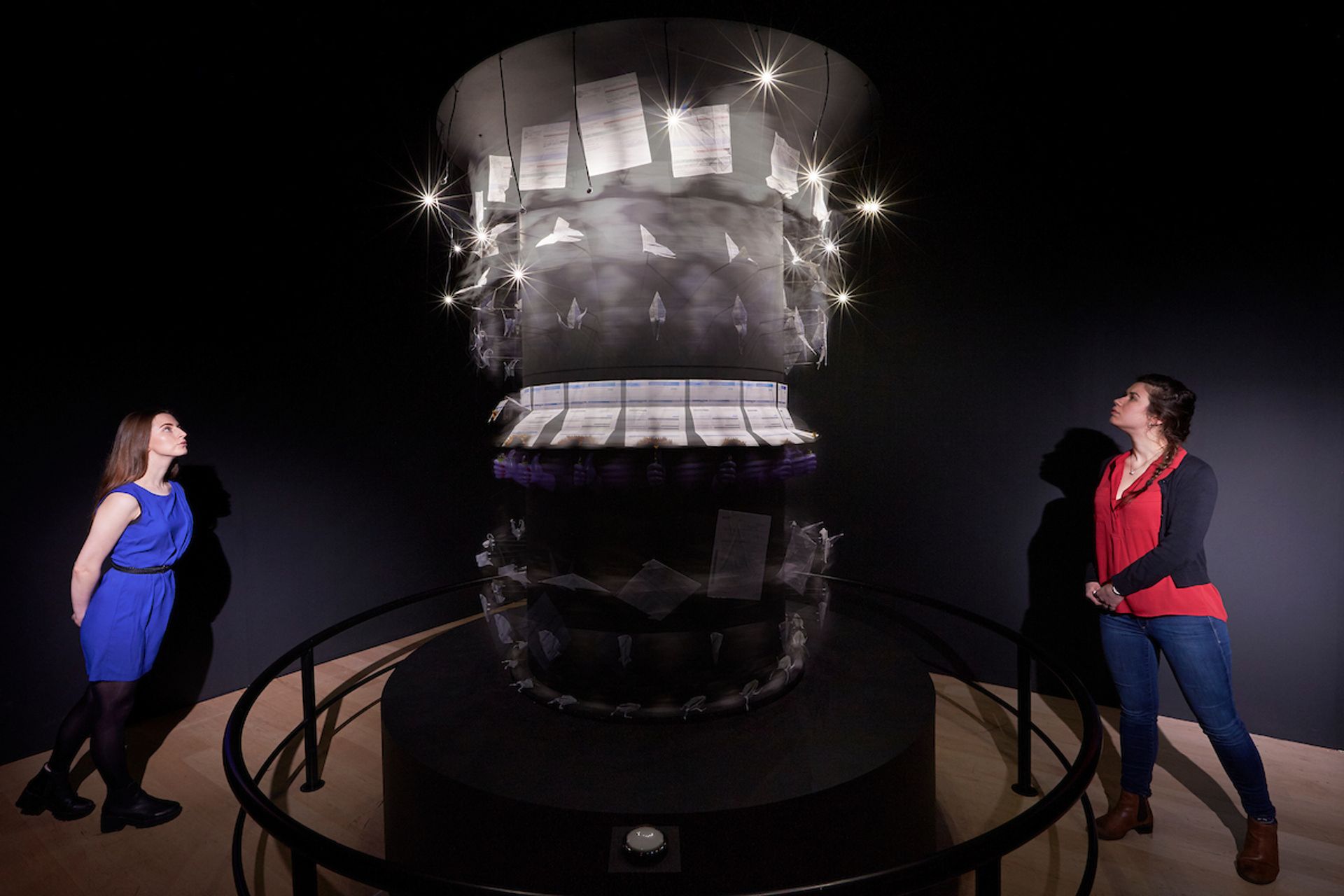

Camille Henrot is known for her idiosyncratically encyclopaedic world view that spans multiple histories, cultures and systems of categorisation. Here, she has created a spinning zoetrope that when hit by flickering strobe lights causes a series of origami creatures—fashioned from electricity bills—to repeatedly fold and unfold. Also on this dramatic carousel of never-ending excess and consumption, life-sized hands perpetually spark up cigarette lighters in an attempt to set these bills on fire.

There is more drama in John Gerrard’s mesmerising slow-motion simulation of a floating frog, which refers to early 18th-century experiments of the effect of electricity on the amphibian’s amputated legs, as well as more recent investigations into whether a frog can reproduce in zero gravity (it can).

Lastly, Bill Morrison’s film takes the form of an animation inspired by images from the Electricity Council archive at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, which were originally developed in the mid-20th century to show people how electricity could be safely brought into the home.

This trio of new works is accompanied and contextualised by a display of more than 100 objects selected from the Wellcome’s holdings, ranging from ancient spark-inducing amber and early electrostatic generators to radiographs, photographs, models and films. Electrifying, indeed.

Queer British Art 1861-1967, Tate Britain (until 1 October)

This is as much a slice of social history as an art exhibition, spanning as it does the century-plus between the abolition of the death penalty for sodomy in 1861 and the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality, marked by the passing of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act. A complicated history of sexuality and desire plays out in a rich parade of imagery, artefacts, ephemera and anecdotes, from the first roomful of seethingly repressed Victorian homoeroticism to the final gallery hung with the painted sexual tussling of Francis Bacon and David Hockney’s gay imagery.

There is a great deal to read as well as to see. And some of the stories are heart rending. The arrest of Simeon Solomon for cottaging in both London and Paris brought about his ruin and he spent the last 20 years of his life in St Giles workhouse. We now know the outcome, but there’s still a frisson on encountering the Marquess of Queensberry’s calling card left for “Oscar Wilde posing as somdomite [sic]”, especially when it is to be found near a full-length portrait of Wilde in his prime, which in turn hangs next to the original door of Wilde’s cell in Reading gaol.

More cheering are Noël Coward’s vermillion monogramed dressing gown; the display of the wickedly funny collaged adjustments made to the covers of Islington library books by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell; and a brimming box of more than 200 brass buttons, each one assiduously collected by the artists Dicky Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller after a uniformed sexual encounter.

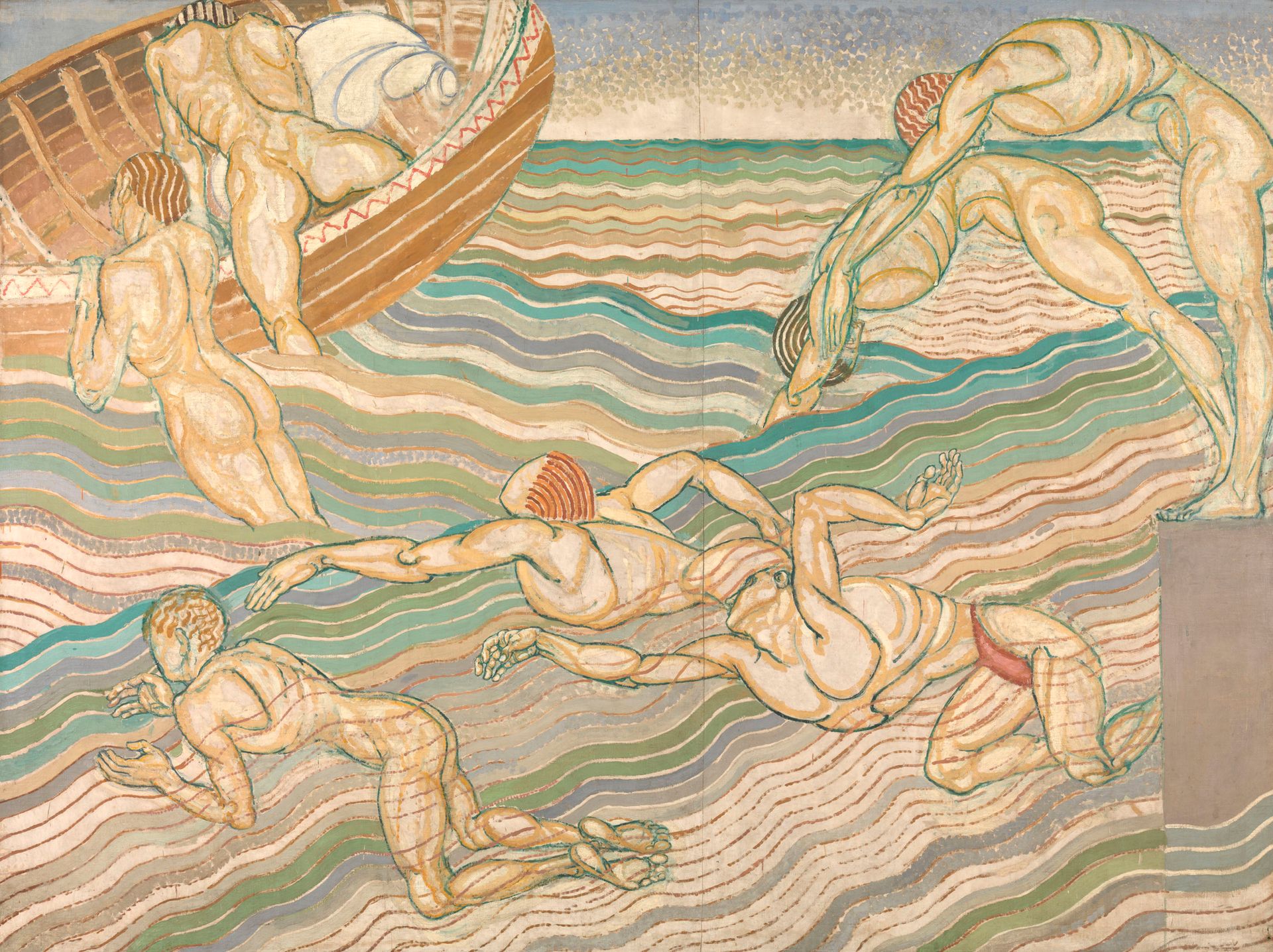

Then of course there are some exceptional works of art. As well as Duncan Grant’s schematic swimmers—at the time deemed too erotic for the dining room of Borough Polytechnic and now owned by the Tate—there is a vitrine of his powerful erotic drawings. Other highlights include Gluck’s forthright chin-jutting self-portrait; William Strang’s depiction of Vita Sackville-West, resplendent in a dashing red hat; and Laura Knight’s audacious 1913 rendition of herself painting a rosy buttocked female model. Edward Burra’s luminous watercolour of pneumatic soldiers lounging in commedia dell'arte masks also presents a strikingly unorthodox view of the wartime military.

But inevitably all of this is only a partial and selective view. Each room of the show—and pretty much every one of its cast of characters—could be expanded into an endless series of exhibitions. And let’s not forget that it also only goes up to 1967. More, please.