The outgoing chairman of Tate, John Browne (Lord Browne of Madingley), has written an impassioned foreword drawing on personal experiences for the catalogue of Queer British Art 1861-1967, which opens this week at Tate Britain in London (5 April-1 October). The exhibition—which includes works by Francis Bacon, Claude Cahun and Angus McBean, among others—marks the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in England and Wales.

Browne, the former chief executive of BP and now the chairman of the Chinese company Huawei Technologies, writes: “When I turned eighteen in 1966, consensual sex between two men was a crime. The following year, the Sexual Offences Act became law, decriminalising sex between consenting men in England and Wales.” He nonetheless resolved to keep his sexuality a secret. “I remained in the closet, hiding my true identity, until 2007.”

He notes that the secular shift in attitudes in the past 50 years has been slow in coming. “Our ability… to expose our audience to a once taboo topic demonstrates the progress made in the past 50 years. But the fact that this is the first exhibition of its kind shows that society has yet to fully accept LGBTQ+ culture. Until it has, Tate will continue to lead,” he writes.

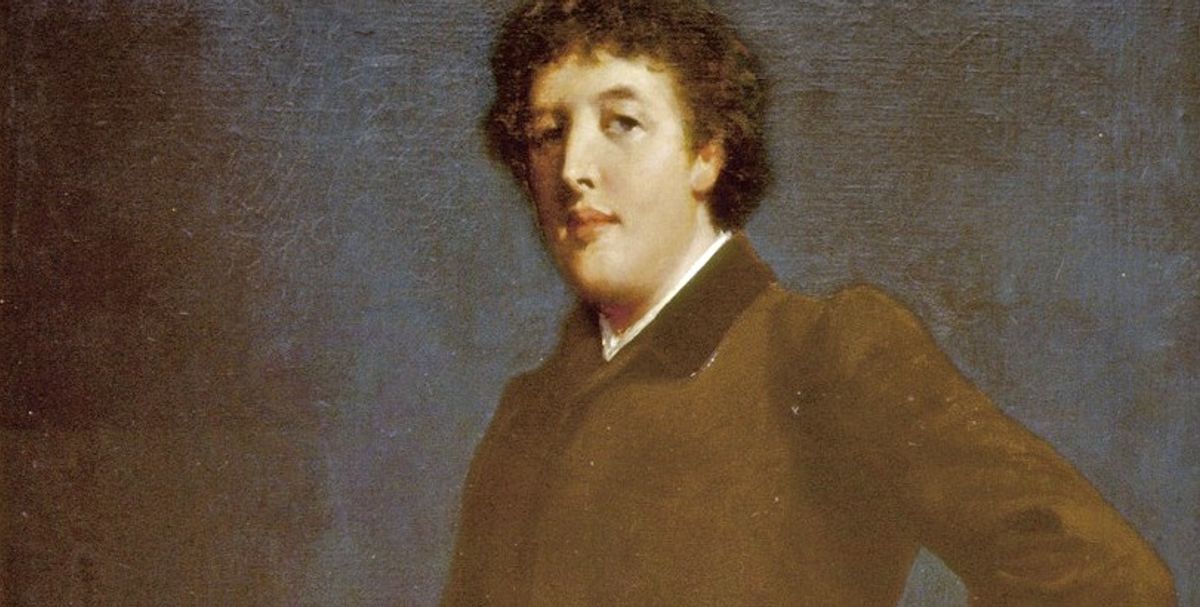

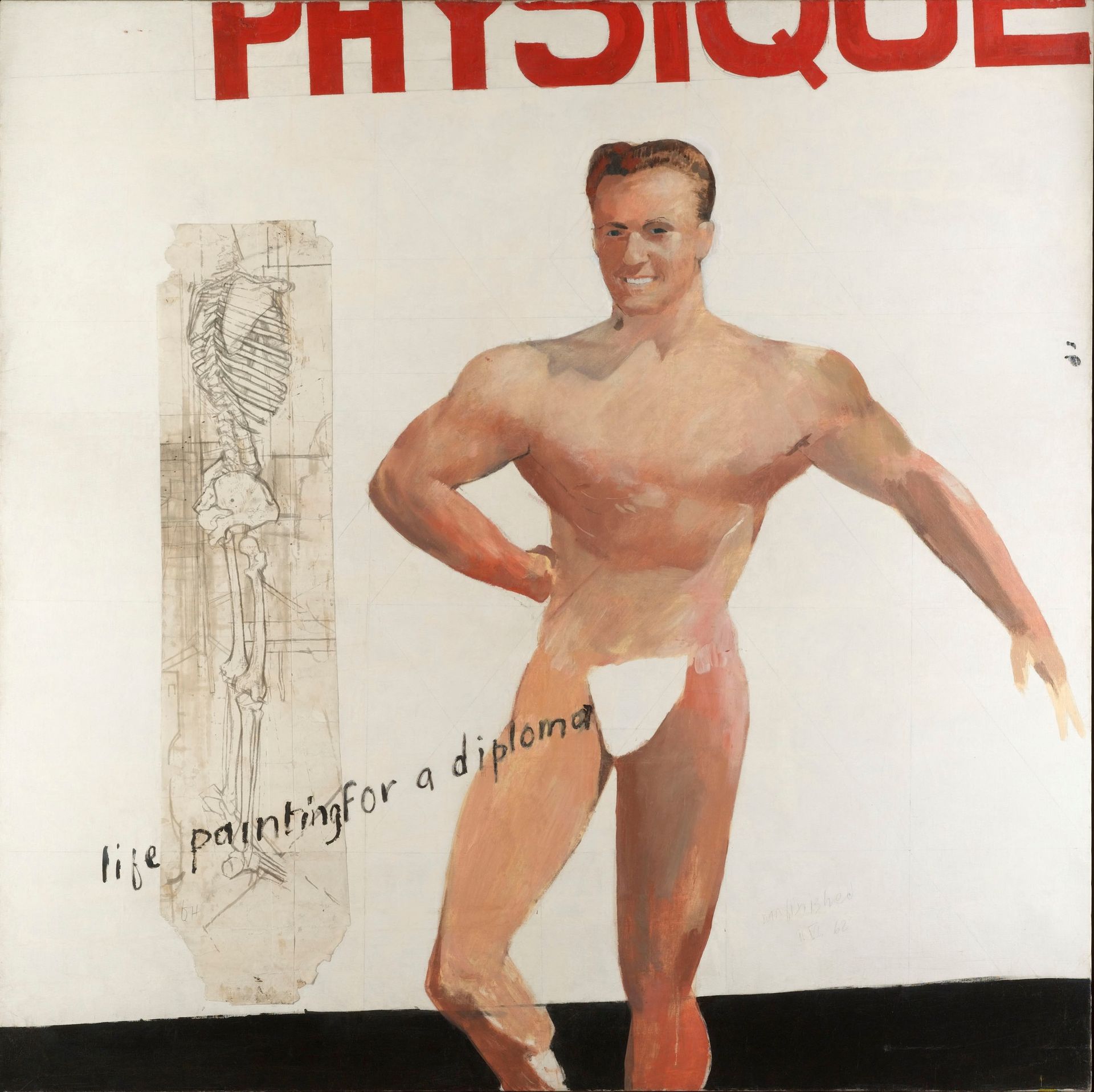

The show includes a portrait of the writer Oscar Wilde, which had to be sold off after Wilde was convicted of gross indecency in 1895. The work has returned from the US for the first time in nearly a century. Robert Harper Pennington, the US artist who painted the full-length portrait (1881), gave it to Wilde and his wife Constance as a wedding present in 1884. Other key works include David Hockney’s Life Painting for a Diploma (1962); Duncan Grant’s vast mural Bathing (1911), made for the dining room at Borough Polytechnic in London; and Hannah Gluckstein’s self-portrait, Gluck (1942).

The use of the term “queer” in the title might raise eyebrows but Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain, defends the term in his foreword, saying: “Once a pejorative, the communities against which it was used have since reclaimed and transformed it into an expression of affirmation and self-empowerment.”