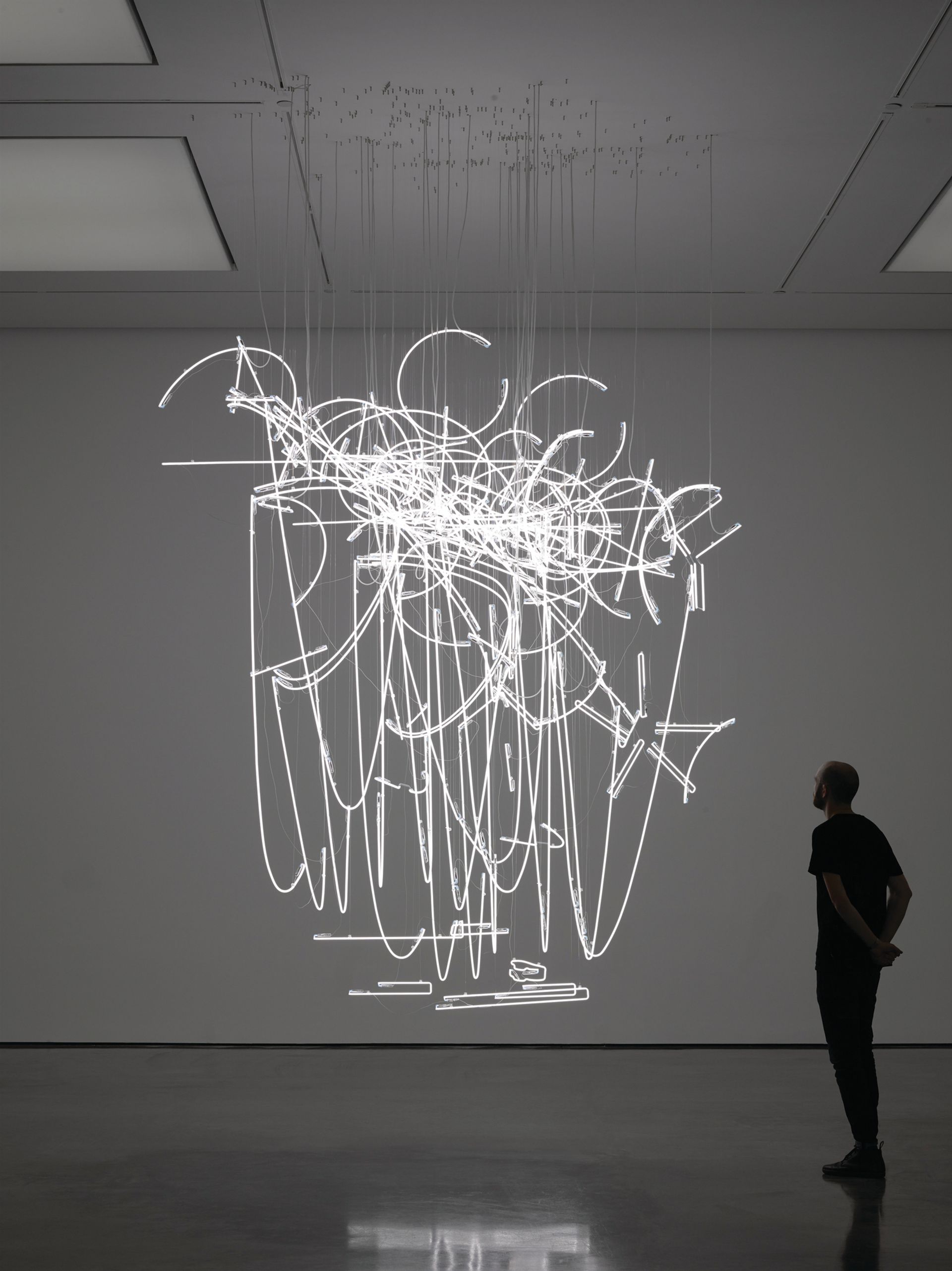

Cerith Wyn Evans first emerged as a key figure in the 1980s alternative scene in London, where he collaborated with the likes of dancer and choreographer Michael Clark, cult performer Leigh Bowery and the Neo Naturist group, while also making his own experimental films and videos. Since the 1990s, he has built a reputation for site-specific sculptural works that often use light and deal with notions of time, language and perception. This year is his busiest yet. He has been selected by Christine Macel for Viva Arte Viva at the Venice Biennale in May as well as for Sculpture Projects Münster in June. Also in June, a show of new work opens at Marian Goodman in Paris. And he has just unveiled a major new work involving nearly two kilometres of white neon suspended throughout Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries.

The Art Newspaper: In developing ideas for the Tate Britain Commission you have to consider the space and heritage of the Duveen Galleries, as well as your relationship to them and Tate’s collections—and yours runs pretty deep.

Cerith Wyn Evans: I’ve known the Duveen Galleries for many, many years. My first visit to the Tate was when my Dad drove me up to London to see the Rothkos for my 12th birthday present, but the Rothkos were not on display, which was something of a disappointment. Then Alan Bowness [who was later director of the Tate] wrote me a letter inviting me back to see the Rothkos and a few months later he met me in person and took me backstage downstairs. I think there were four that you could lift the polythene off.

You sound like a very advanced 12-year-old.

Growing up in Wales, in the shade, art was my only escape. I’d read [Patrick Heron’s] Changing Forms of Art by the time I was 11 and I used to get Llanelli library to import Studio International and Flash Art for me; this stuff was my lifeline. From when I was a student at St Martin’s I worked as an invigilator at the Tate on and off for years, so I knew the collection inside out.

What were your thoughts about the Duveen space itself?

Making work on that scale is a challenge and you have to consider the implications on a narrative level of a space which, is, as the French call, enfilade: one going on from the other. It’s very hard to remember how tall the Duveens is, so I wanted to work in the air and to occupy the volume of the space. I wanted there to be nothing on the floor and to challenge the notion of how you occupy the space “sculpturally”. I decided to carry through a strain that has run through my works of the past five years and attenuate the medium right down to just these white neon drawings in space. I’ve been looking at Duchamp, I’ve been looking at technical drawings, I’ve been looking at the notion of The Illuminating Gas [part of Duchamp’s last work, Étant donnés]. I’ve been reading [the artist and writer] Hito Steyerl, I’ve been talking to Eric Alliez who wrote this extraordinary book, The Brain-Eye, and I hope is going to do an intervention-lecture. Then I’m fully aware of the echo that your shoes make and I’m also familiar with the vicissitudes of how the light falls into the galleries. The space is so golden in the afternoons on a sunny day, the walls are like honeycomb.

In the South Duveen there is just a single neon ring. Can this be seen as a giant peephole?

It’s a peephole, a porthole and the circle with an arrow that signals “you are here” on old paper maps where successive fingers have worn out the space. I’m playing with the idea of it being the literal hic et nunc, the here and now, like being told on the GPS exactly where you are. In a sense, the whole piece is a critique of the scopic field and hierarchies of scopic regimes. I’m trying to interrogate very basic ideas around the tools of mimetic representation and lifelikeness such as one-point perspective. What I am saying is, let’s look at looking again.

In the central Octagon space, three suspended neons take their form from the “Oculist Witnesses” in Duchamp’s Large Glass. In the Large Glass Duchamp takes a two-dimensional diagram lifted from an optician’s eye chart and he stacks them on top of each other in a kind of volumetric sideswipe in space-time. What I’ve done is upend the whole thing and knock them off register: they’re just “spot off”. So in the Octagon you have a kind of overture which looks at all the themes and leitmotifs. You also have the sightlines that go directly into the Tate collections to the left and right, as well as into the North Duveen where the structure becomes a different thing.

Can you talk about the origins of the dense, dangling mass of hanging lines, curves and circles in the North Duveen?

The forms originate from the Kata diagrams that are the movement patterns made for performers in Japanese Noh theatre. The diagrams show how to perform a particular role and specifically how to address the choreology [the notation of movement]: the footsteps, head gestures, the stamps on the floor, the flicking of the kimono, position of the fan. They look at the transformation that happens in every Noh play, between the person who is there to recount their story as if they were on earth who then transforms into the true spirit of whom they are. So it’s about these places where there is a hinge into a transformative mood, activated by the steps. The elements will be close enough that you can see the electrodes at the end of each neon gesture and line, and see that they are all connected electronically to other parts. The whole of the Duveen Galleries presents a kind of ethereal, subtle body which takes the notion of perception into visible and invisible realms.

Does the audience need to be aware of the work’s multiplicity of references?

There are many layers to it and multiple points of entry. Very importantly, my take is not the only take on it. If anything it’s a kind of zone for meditation and a place for reverie on the transference of energy. I feel there’s an insufficiency of means to come to even a conventional description of what it is to live through a revolution in information technology and to look at the exchanges of energy that go across the surfaces of the earth, let alone what fantasies we might have about parallel realities. I want people to be in a place where they might be able to pick up on some of these things.

You’ve said that you are never comfortable with facts, inviting one interviewer to “come with me into this place of contradiction”.

I feel there’s a need to get into the thick of what our lived experience is at the beginning of the 21st century. Everyone is looking at a screen, everyone is being controlled by hidden hierarchies, energy power structures, globalisation, re-territorialisation and the trade of invisible stocks and bonds that we are all somehow subject to. What’s occluded by this call for clarity? What is this notion of fake news? For me a successful work is one that is un-photographable. My friend, the great artist and Duchamp scholar Molly Nesbit, talks about my work as “a rendezvous of question marks”, which I like very much.

What are you showing at Venice and Münster?

Christine [Macel] has invited me to show my 1998 film Firework Text (Pasolini) in Venice [see sidebar] and I’m making a new sound and light piece for Münster. There’s an extraordinary Brutalist church that was built outside the city centre just after the war and I’m installing an air conditioning device in the bell tower which lowers the temperature so that the bells will be ringing at a higher pitch, as if it was a freezing cold day in January. I’ve also taken two sections of horizon from German Romantic landscapes that I have made in two slightly different shades of white neon. These will be upended and buried in a pale pink floribunda rose bush which grows against the church wall.

• Tate Britain Commission 2017, Tate Britain, London, 28 March-20 August; Venice Biennale, 13 May-26 November; Sculpture Projects Münster 2017, 10 June-1 October